Greece. A land of rich history, catastrophic recession, and, apparently, far too many pharmacists.

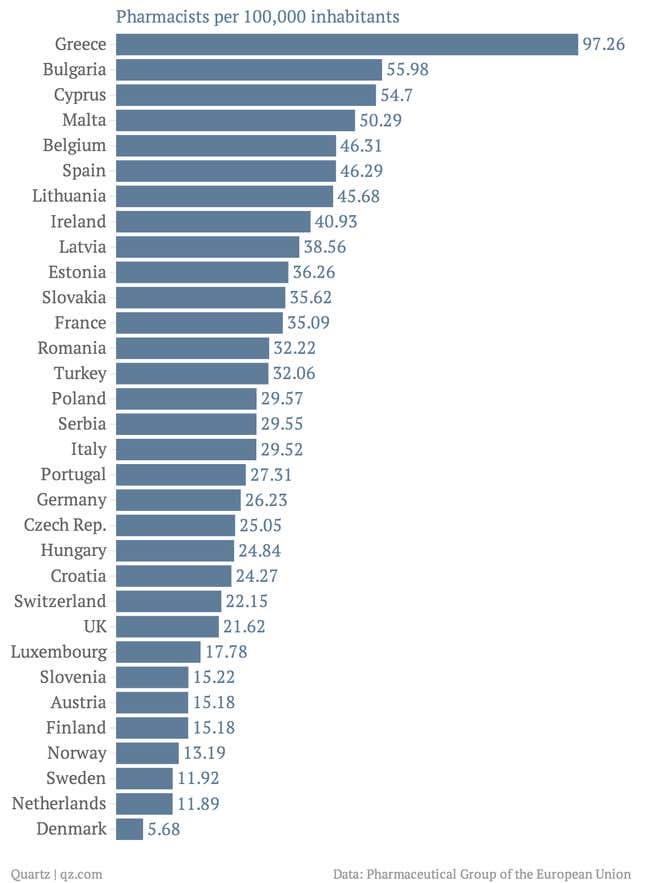

In fact, Greece has the largest number of pharmacists, per inhabitant, in all of Europe. On a per capita basis, there are more than twice as many Greek pharmacists as French or Spanish ones, 74% more than in Bulgaria—Greece’s nearest competitor in druggist density—and an astonishing 17 times as many as in Denmark.

To what does Greece owe its white-coated army of pill-providers? Well, they benefit from a slew of rules that would seem almost tailored to keep competition at bay.

According to the OECD, Greece is one of the few EU countries that sets prices for over-the-counter drugs, such as aspirin, and restricts their distribution solely to licensed pharmacies. Regulations limit the ownership of pharmacies to actual pharmacists (and each pharmacist is allowed to own only one). They dictate where new pharmacies may open, based on population and distance requirements. They set opening hours; pharmacists who wish to work beyond those hours must inform their local pharmacists’ association and the local prefecture. Pharmacy owners must employ one actual pharmacist for every three assistants. The list goes on.

The result of all these rules is a tidy little cushion of profits. The OECD reports that the retail margins for Greek pharmacists, as a share of final retail price, are more than four percentage points higher than those of pharmacists elsewhere in the EU.

You could argue that artificially propping up profits at pharmacies is a legitimate policy choice Greece made to ensure access to medicine throughout the country, including in far-flung rural areas. Unfortunately, Greece essentially lost the right to make such choices when it turned to the troika—the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Central Bank—in order to be bailed out of its debt crisis.

Those loans came with strings attached. And the troika continues to pull them. In its current round of negotiations with Greek policymakers, the troika is pushing them to ease restrictions on over-the-counter drugs, including letting them be sold in other kinds of stores, such as supermarkets.

Greek pharmacists see this as an existential threat. (For many, it is.) Changing the rules, they say, will result in the closure of 11,000 pharmacies and the loss of more jobs in an already beleaguered economy. This week, pharmacists closed up shop for two days in what they called a “warning” strike. “Medicines are not consumer products. Competition and healthcare are incongruous concepts,” Kyriakos Theodosiadis, head of the country’s pharmacists’ union, recently said.

Pharmanomics

Why do Greece’s creditors care about how it sells pills, though? After all, Greece’s dire economic straits are fundamentally down to an excess of debt, not druggists.

Well, the theory is that more competition would push prices lower, boost retail sales and offer a push to the economy. And to be fair, changes to the pharmacy sector are just a small part of the 329 reforms the OECD recommended to make the Greek economy more competitive. The organization estimates the combined benefit of all these measures at around €5.2 billion ($7.2 billion) or 2.5% of GDP. And it stresses that Greece must follow all of its recommendations to ensure it recoups the all benefits. The authors of the OECD report note that “partial lifting of restrictions will yield only partial results.”

Imposing such conditions is a political necessity for Greece’s creditors; the troika has lent Greece roughly €240 billion since 2010, and these loans are deeply unpopular with voters in many of the lending countries, so demanding reforms is seen as a minimal assurance that they stand a chance of getting the money back.

However, that doesn’t mean those reforms are the right thing for Greece’s economy.

Economists have looked for the economic benefits of IMF-administered programs, and they haven’t found many; often, in fact, the opposite. A paper published in 2003 (pdf) by Robert Barro of Harvard University and Jong-Wha Lee of Korea University found “greater IMF loan participation has a direct negative effect on economic growth.” The next year, research produced a similar result (pdf). “What I find is, basically, that IMF programs reduce growth rates,” wrote Axel Dreher, an economist at Germany’s University of Heidelberg. Yale economics professor James Raymond Vreeland, summing up the research in 2007 (pdf), wrote that “the most recent studies, using the best available methods, find an historically negative effect.”

What’s more, Barro and Lee found that in countries that took part in an IMF program, democracy and rule of law declined slightly. Other studies, they note, have found that foreign aid has a similar effect on rule of law, suggesting that all that money sloshing around encourages corruption.

At any rate, whether it’s due to the IMF or just the atrocious economy, Greek democracy is clearly under a strain. Voters are increasingly turning to formerly fringe political parties—anti-austerity Syriza on the left and neo-nazi Golden Dawn on the right—and away from the parties willing to work with European lenders.

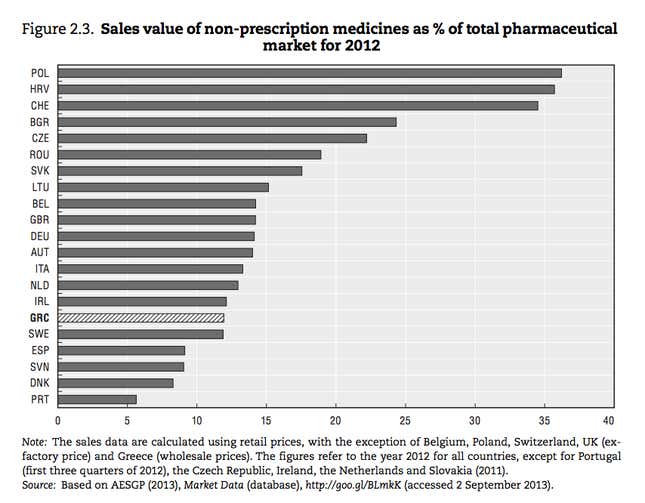

Through this lens, the idea of Greece fighting to keep its pharmacists seems a lot less silly. It’s really about the country being able to decide its own priorities. (Greece might pay its pharmacists too much, but, because drugs are therefore more expensive and harder to buy, Greeks don’t spend as much on them as a lot of other countries. And despite that, they still rank respectably well in broad measures of health.)

So, sure, Greece’s pharmacy sector is probably pretty inefficient. And Greeks are likely overpaying for prescriptions. But people were used to the way things worked. Now change is being forced from outside. And that’s a pretty bitter pill.