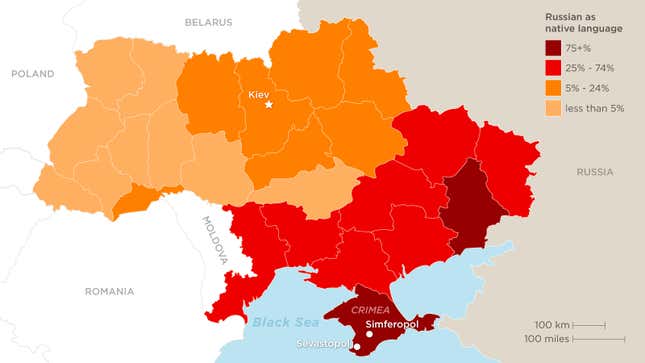

The fault line that divides Ukraine into pro- and anti-Russian chunks may be more than just linguistic, ethnic and political. Ukraine is also split by sharp disparities in life expectancy, as a new article in The Lancet points out. In 2009-10, the latest years for which data was available, western Ukrainian men lived approximately 4.9 years longer than those in the east and south, while women lived 4.4 years longer, according to a Ukrainian study.

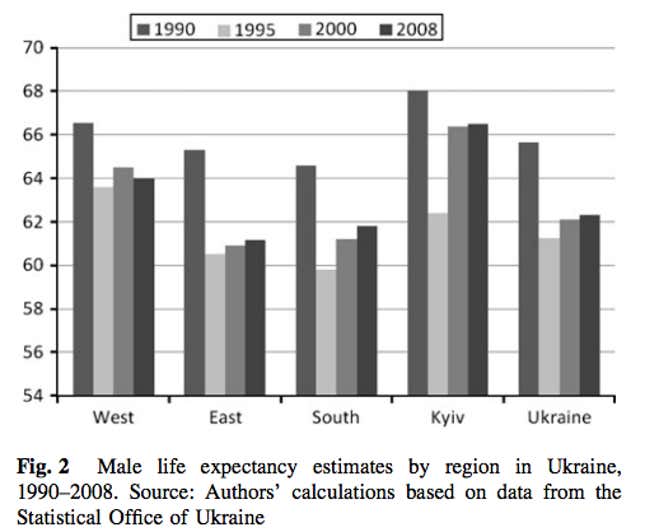

A more systematic analysis of 2008 data (paywall) found life expectancy for men in west Ukraine was 64 years, compared with 61.8 years in the south and 61.2 years in the east, with a similar pattern among Ukrainian women. Here’s a look:

Why the divergence? Various studies have found that heavy boozing (pdf, p.331), smoking, drug abuse and risky sex are all more common in Ukraine’s southern and eastern regions—as are violent deaths and infectious diseases.

The composition of Ukrainian-killers has changed over time, though. Back in 2000, heart and lung diseases linked to alcoholism and smoking were mostly responsible for easterners and southerners dying younger. “External causes” such as suicide and alcohol-poisoning were also problems.

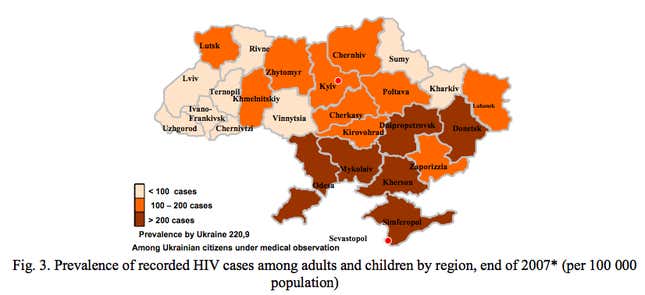

While those causes were still killing people, eight years later infectious disease had emerged as a new threat. Tuberculosis was the biggest killer overall, though the fact that it was so lethal among those aged 24-44 suggests that TB killed people whose immune systems were already compromised by AIDS. That squares with surging HIV/AIDS rates in the east and south. For instance, in the provinces of Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, Odesa, Mykolaiv, the city of Sevastopol and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, prevalence rates are 361.6 to 605.9 per 100,000 people (pdf, p.13), compared with the national average of 264.3 per 100,000. That’s dramatically more than the 154 per 100,000 in Georgia (pdf, p.18).

But even in the relatively healthier west of the country, Ukrainians were still living much shorter lives in 2008 than they were before independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 (with the exception of women in the west and in Kyiv). Back then, men lived to 65.6 and women lived to 75.

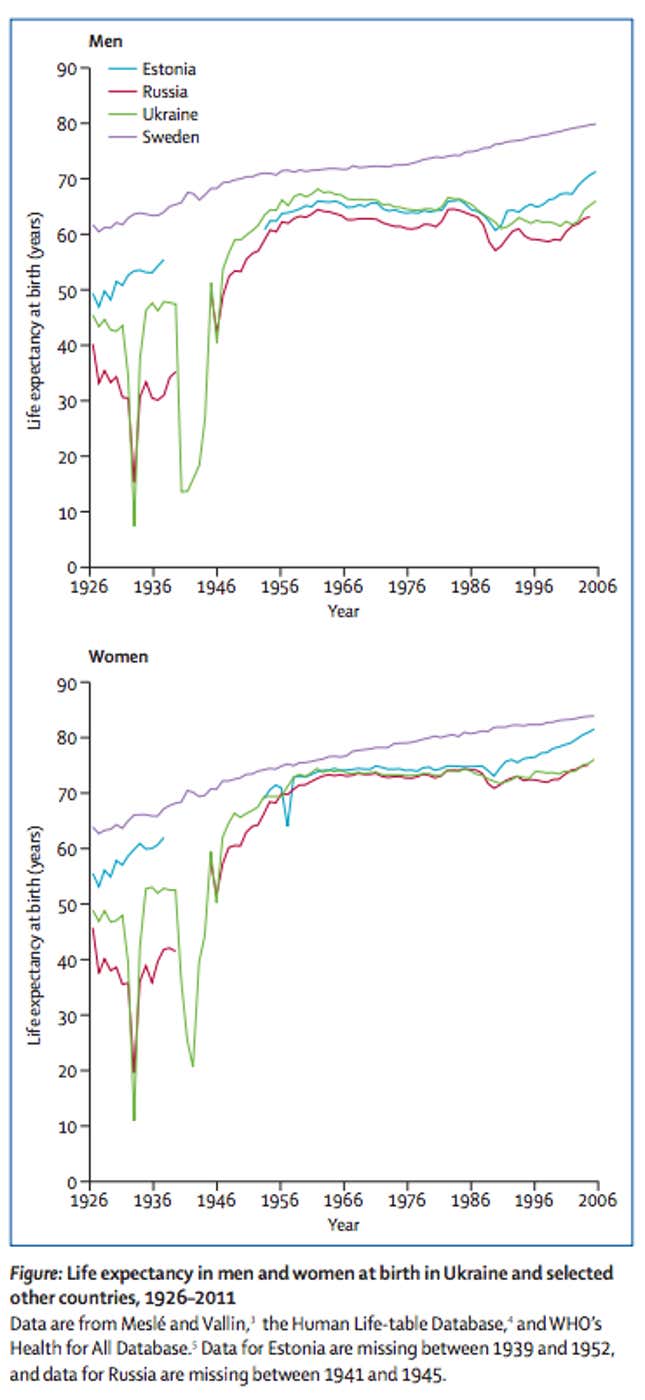

Of course, Ukraine is not the only former Soviet state to see its life expectancy rates crater in the aftermath of independence. But most of those countries saw their rates begin to recover in the mid-1990s. Like Russia, Ukraine didn’t start improving until 2005. Here’s how it stacks up against Estonia, Russia and Sweden:

The authors of the 2008 report chalk up some of Ukraine’s post-independence struggles to deteriorating social conditions, higher rates of incarceration (disease is spread more easily in prison), and, increasingly, to the rise of drug-resistant strains of diseases that result from health policy failures.

The report highlights one of the biggest challenges for the new government: Ukraine’s dreadful public health system. And this isn’t just a humanitarian matter; considering the country’s rapid population decline—it has fallen from 52 million in 1990 to 46 million today—the crisis is also economic. Allowing curable or preventable diseases to keep blotting out Ukraine’s working population will only make it harder for the economy to recover.