Everybody seems to have it in for London. Writing in the New York Times last week, Ben Judah decried Britain’s capital as a ghost town of empty mansions owned by Russian oligarchs. Yesterday, Cory Doctorow of the blog Boing Boing has a separate but related complaint: Shoreditch, the part of London favoured by tech startups, is being overrun by new developments! And student housing! And incubators! Meanwhile, Ben Southworth, the founder of a Shoreditch-based “content, promotion and events company“, is busy opposing a planned development on the site of the long-disused, boarded-up Bishopsgate Goodsyard. “We don’t want the area to lose its soul and heart,” he tells the Evening Standard.

What is going on? Has London truly become an ultra-gentrified town run over by “oligarchs’ dirty billions” (in Judah’s words) and ”war criminals’ money” (in Doctorow’s formulation)? More specifically, are people going to Shoreditch simply “because it is a popular area and makes a good investment case” (according to Southworth)?

No

Judah’s argument has been dealt with in the pages of the Financial Times (twice) and City AM, so there seems little point rehearsing those rebuttals. More of interest to me, as a reporter who covers technology, is what Doctorow and Southworth have to say about Shoreditch. And this is what it comes down to: “We got here first so shut the door and don’t let any of those new people in, even if they have lots of money. Especially if they have lots of money.”

After all, a new development with tall towers might overlook the private club’s members’-only swimming pool at the top of the Tea Building, occupied largely by tech startups. That wouldn’t be in keeping with the scrappy DIY ethos of the place at all, not if outsiders can waltz on in with their tall buildings and dirty money. This isn’t the argument you hear in San Francisco about how gentrification is pushing out poor people (itself wrong-headed). Instead it is the tech folk themselves, the first wave of gentrification, complaining about the next wave.

Doctorow’s primary complaint boils down to rising rents, which he blames on misguided development policies at the local council, Hackney. That rents are going up is indisputable: According to estate agents Stirling Ackroyd, they have doubled in Shoreditch in the past two years. “Unless start ups can find affordable space within the numerous tech hubs, incubators and creative shared spaces now establishing themselves in the area, many are being pushed out of the area,” Stirling Ackroyd writes.

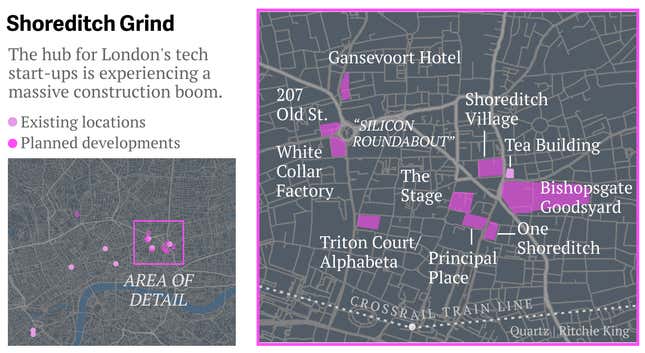

But blaming the council seems unfair when all of London is undergoing a massive construction boom, with new towers sprouting up in the City, Southwark, Vauxhall and anywhere else that will have them. Hackney, routinely ranked among the poorest districts in London, would be remiss to not cash in.

Where Doctorow gets it wrong is in standing up for startups as oppressed innocents. The tech sector is largely responsible for the morphing of Shoreditch into a place that now attracts all the developers Doctorow dislikes. It became desirable precisely because young tech workers came in eager to socialize, eat and drink, and live close to work. Up-market bars, restaurants and hotels followed them. That has put pressure on rents. Hackney may, as Doctorow complains, have made the market for startup space tighter still by destroying some old industrial spaces to build high-rise towers, but the trend of rising rents was there already.

More supply, not less

As Quartz has previously reported, large companies are following the startups to be part of the tech district. This is not always a bad thing. Few aspiring entrepreneurs in Shoreditch would tell you that the Google Campus, which provides free working space and wifi, is a bad thing. If anything, the district needs more such spaces, and more large offices to add some diversity to the “circulation of talent and ideas at speed, through invisible personal networks” that Doctorow lionizes. What it does not need is NIMBY-ism from the very people who transformed the area.

The solution then is precisely the opposite of what Doctorow and Southworth want. The answer is more development, so that there is more available property, particularly of the sort that the same large, deep-pocketed companies will want to move in to. Building new towers adds supply, which should ease the pressure on rents somewhat—or at least bring it down to the (still ridiculous) levels of increase common in London. And as startups get bigger and turn into large companies themselves—surely what most of them aim for—they too will want bigger, better spaces. It is both in their own interests, and the interests of the startups that will come after them, for there to be big spaces for them to move into as they grow.

And what if that doesn’t work and prices keep rising regardless, forcing businesses out of Shoreditch? Doctorow asserts: “Scattering Silicon Roundabout’s startups to the winds may not kill all of them, but it forecloses on many of the startups that are yet to come.” This is patently false. The sector has already spread to West London and to the Canary Wharf business district. A giant new development is underway on the site of the Olympic Park’s media center. Indeed, it takes a spectacular failure of imagination to think that for a sector to survive it must stay in one tightly-constrained neighborhood. Silicon Valley leads the world despite being spread over hundreds of square miles.

What Doctorow and Southworth are really arguing is that they want it both ways. They want the character of Shoreditch to remain as they found it, even though their very presence alters the area. They demand attention as the area’s original residents, but shed few tears for the Bangladeshis, Jews or French Huguenots who came before them. They want more space for startups but would rather that prime property in the middle of a desirable district—like the Bishopsgate Goodsyard—be left empty and unused than share it with newcomers. Indeed, Southworth has taken it upon himself to tell the world what is and what is not Shoreditch, with a website (pictured above) that says precisely that, not through argument or data but with evocative images of a lovely neighborhood unsullied by commerce (or poor people, or brown people).

There is also an undercurrent of xenophobia. It’s these foreigners who are to blame, whether they come from Qatar and Russia—the favourite examples of ill-gotten gain in the British press—or China and India with their classless nouveau-riche crowd. Doctorow himself can hardly be a xenophobe; he was born in Canada but naturalized as British in 2011. Yet even he plays to the anti-foreign prejudice with his talk of war criminals’ money and his complaint about the council allowing a development whose function is not to house hedge funds, but “wealthy overseas students.” Would it be okay if the students were British or poor? He doesn’t say.