On first glance, Canadians seem like fairly reasonable people.

Sure, they love hockey. And they have a bizarre system for selling beer in Ontario. But on the whole, Canadian society exudes sensibleness.

Then you look at their household debt levels.

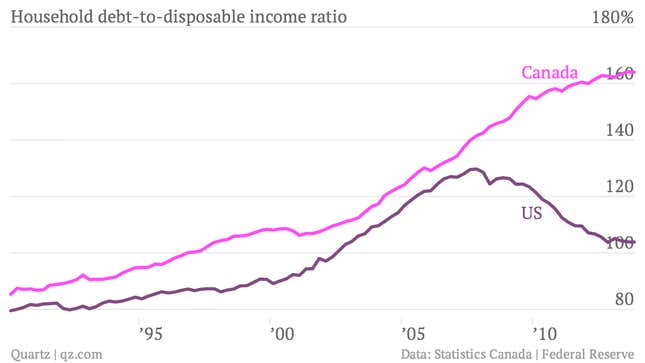

True, just-released data seem to suggest that household debt levels are stabilizing a bit. But at 164% of disposable income, they’re still quite a bit higher than US household debt-to-disposable-income levels were even at the height of the pre-crash credit boom (roughly 130% of disposable income). Because Canada missed the worst of the global financial crisis, its household sector never underwent the so-called de-leveraging—a period of cutting debt loads—that has weighed so heavily on the US economy over the last few years (as the chart below shows).

Low interest rates fueling a boom in mortgage lending are responsible for the recent surge in Canadian household debt. And that mortgage boom keeps the country’s overheated housing markets burbling. (According to Goldman Sachs analysts, Canada has one of the frothiest real estate markets in the world.)

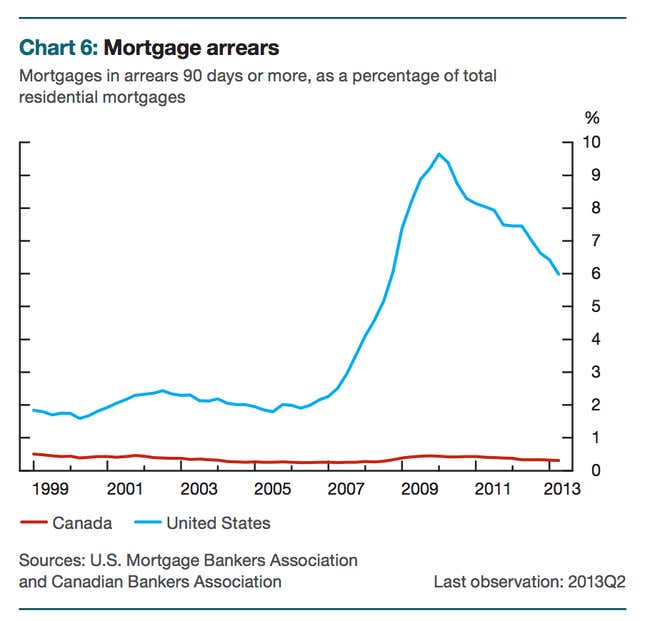

Sounds a bit familiar doesn’t it? So is Canada doomed to repeat the mess south of their border? It doesn’t look like it. In fact, Canadians historically have been better at paying their mortgages than Americans. That was true even prior to the US mortgage crisis (which left many American homeowners “underwater,” with debt higher than the value of their homes).

Why? A key reason is that mortgages in Canada are full recourse, which means you can’t just default and walk away from the house you borrowed upon, as you can in the US. Canadian lenders can come after debtors for their other assets. “The standard full recourse provision for Canadian mortgages significantly reduces the incentive for households with negative housing equity to default, which implies lower direct risk to the financial system from a potential correction in house prices,” said a recent Bank of Canada report.

That doesn’t mean that Canadian household debt can continue to grow at the astronomical rates seen over the last few years. But crisis junkies might want to look elsewhere for their next fix.