Investment drives China’s economy. And housing fuels a large share of that investment, contributing 33% of fixed-asset investment, says Zhang Zhiwei, an economist at Nomura—and, consequently, 16% of GDP. The decade-long housing boom that’s kept China’s GDP aloft has so far defied the bubble warnings, which began as far back as 2007.

But the building binge is finally catching up with China. Not just because sales are faltering (paywall). After building around 13.4% more floorspace each year, China finally has too much housing, argues Zhang in a note this week. The quirks of China’s economic model mean that a housing crash will be more devastating for the economy than many realize.

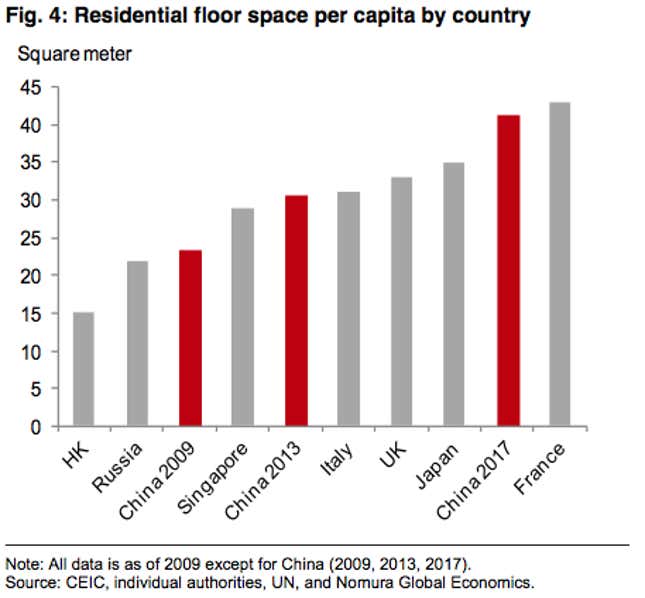

For each person that moves to a city this year, Chinese developers will build around 121 square meters of shiny new flooring, estimates Zhang. That’s double what there was in 2009, and a marked increase from 2013’s 113 square meters. Though residents trading up to roomier digs will absorb some of this, the Nomura folks nonetheless say they “find this alarming,” putting China’s per capita floorspace on par with much more developed markets.

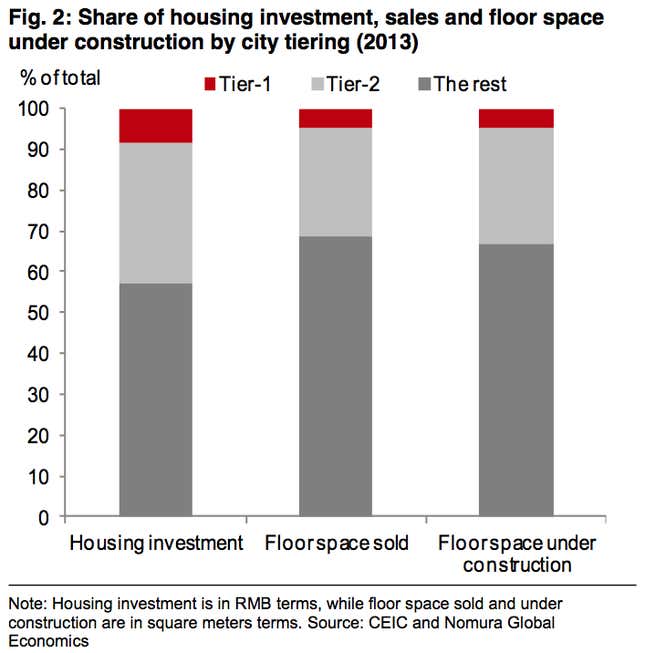

But housing supply is tricky to make sense of when, thanks to China’s closed capital account, apartments are traded like stocks. Despite reports of housing gluts in smaller cities, many take heart in the fact that sales in first-tier cities—Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen—remain robust, thanks to higher incomes among residents, and because people from other cities buy property in the big metropolises as investments.

But those sales may offer a false sense of security, Zhang says, pointing out that first-tier cities account for only 5% of housing under construction and sales—and a mere 8% of overall housing investment in 2013. This “cognitive bias” makes investors ignore the storm clouds gathering within China’s housing market, says Zhang.

“This is comparable to when the US property bubble burst, since property prices did not collapse in New York, but instead in places like Orlando and Las Vegas,” Zhang says. “In China, the true risks of a sharp correction in the property market fall in third- and fourth-tier cities, which are not on investors’ radar screens.”

If China’s housing market crashes, the ripple effect could be even more cataclysmic for its economy than the recent housing market collapses in the US and Europe were for their economies. A fifth of outstanding loans and a quarter of new loans are to property developers, says Nomura; untold billions more have been lent out off bank balance sheets. As falling prices crimp margins, small developers—like the one in the news this week—will start defaulting.

But the fallout will be bigger still, says Patrick Chovanec of Silvercrest Asset Management. ”Not only is property important because it’s a key component of that investment boom, but it’s essentially the asset that underwrites all credit in the Chinese economy, whether it’s local government loans, whether it’s business loans,” Chovanec says, explaining that lenders require “hard” assets as collateral because financial accounts can easily be doctored.

This creates a circular system. ”All these loans are being made on the basis of property as collateral, which then goes into property and bids up the price of property,” he explains. “And then the property price—the price of the collateral—goes up, and you can get more loans. That’s a very dangerous cycle.”