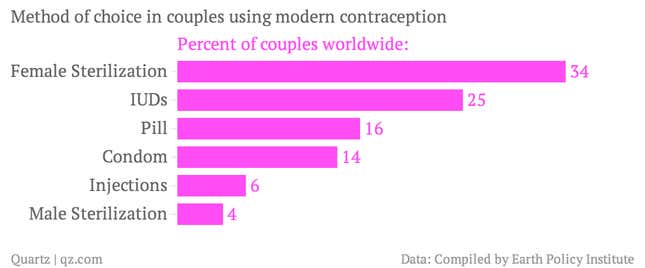

There are a lot of birth-control options, but intrauterine devices (IUDs) are the most widely used worldwide.

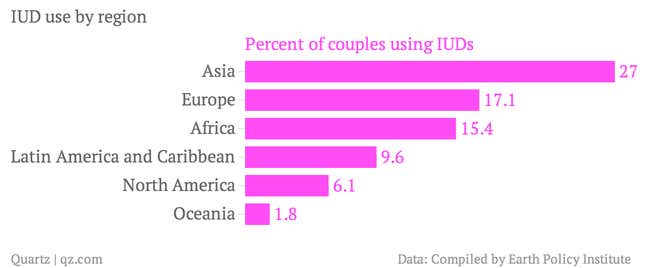

The tiny, T-shaped devices allow women years of highly effective birth control, with or without hormones, and are a great option for basically anyone who a) has a uterus and b) doesn’t plan on having a baby in the immediate future. In fact, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommends IUDs as a first-line contraceptive for most women, including sexually active adolescents. But North American women hardly use them.

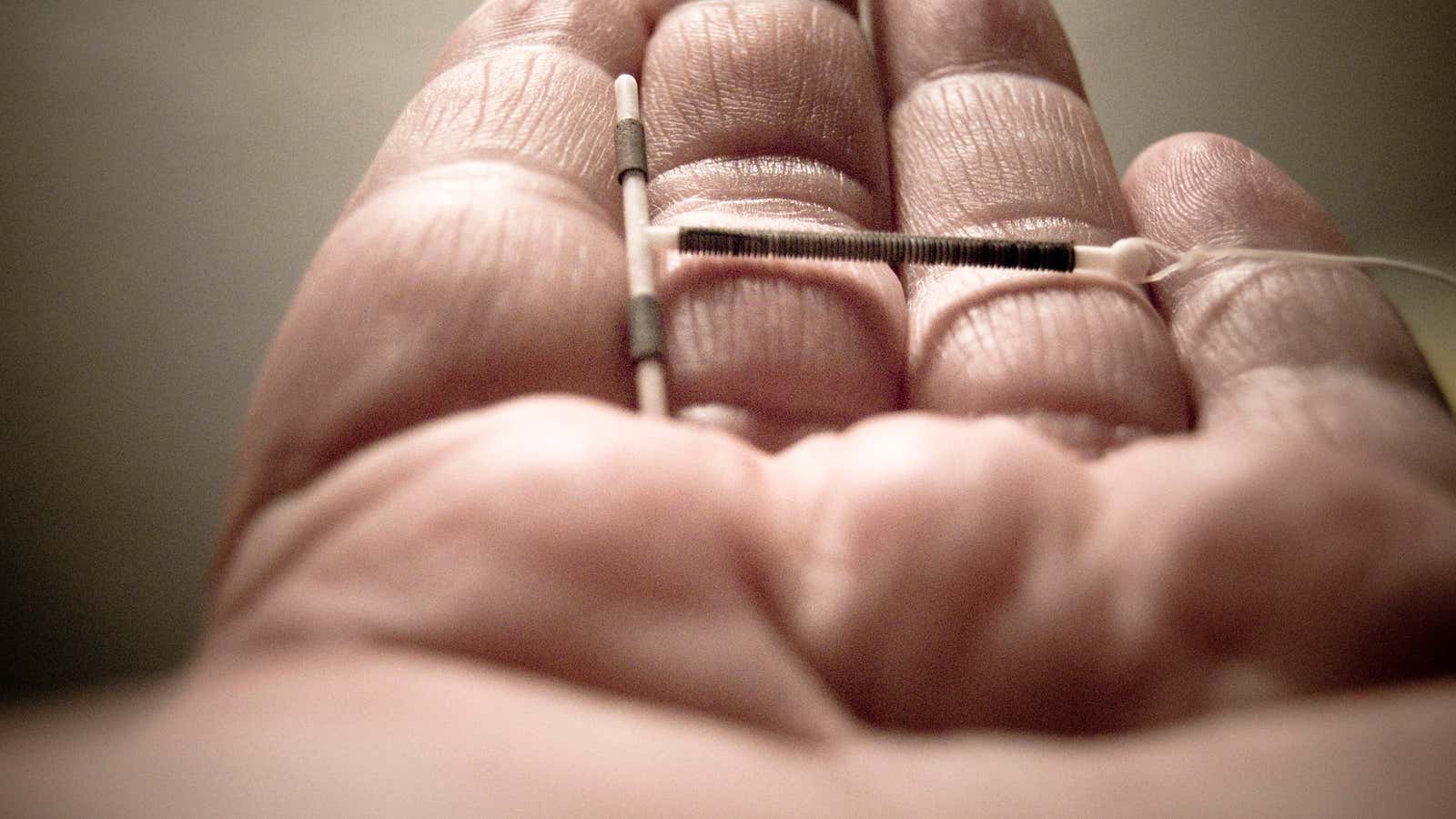

That’s because physicians and pharmaceutical companies in the US and Canada are still dealing with the backlash of this terrifying hunk of plastic:

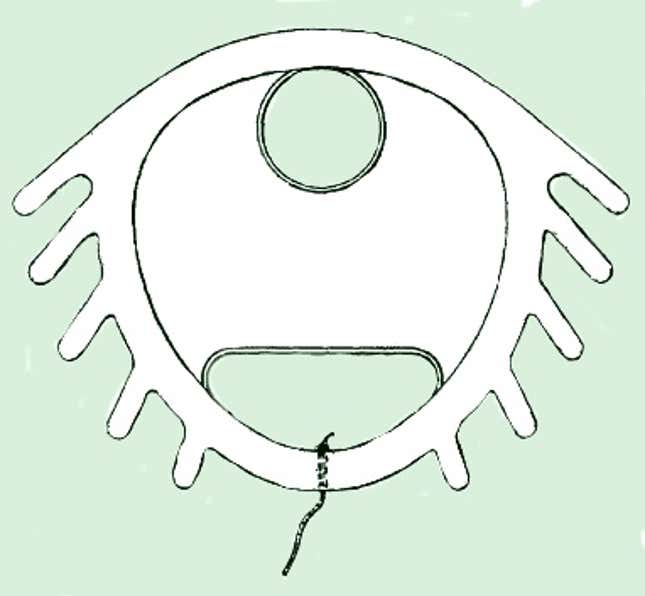

The Dalkon Shield, which hit the US market in 1971, was unleashed on the public after only one small study to prove its efficacy—led by a developer of the device who stood to profit from its sale. No research was done on its possible side effects before sales began. You can probably guess what happened next: Nothing good. The product was taken off the market voluntarily in 1974, and by the time its parent company filed for bankruptcy in 1985 more than 300,000 lawsuits had been filed.

The Dalkon shield’s biggest flaw was not in fact its scary shark-jaw shape (though that didn’t help), but the braided, porous string used to remove it. It hung in the vagina (which is full of bacteria) and led to the uterus (which isn’t) and served as a superb ladder for infections to climb. Once bacteria gets into the uterus, you’re at risk for permanent infertility. It puts any pregnancies at risk, too.

But the Dalkon Shield was a single bad product that managed to spoil US opinions on all IUDs. “They really struck fear in the heart of women who’d used them,” Megan Kavanaugh, who researches IUDs for the Guttmacher Institute, told Quartz. “Dalkon really tainted the market in the US in a way it didn’t abroad.” Many patients—and even physicians—are still under the impression that all IUDs put women at risk for infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and perforation of the uterus. “We used to only recommend them to women who’d had children,” Kavanaugh says, “but now we know they’re perfectly safe for most women. The risks that the Dalkon Shield made people associate with IUDs just aren’t an issue anymore.”

Recent marketing, she says, has caused a pick-up in US interest. US women can choose between Mirena, which releases small amounts of a progestin hormone into the uterus, and ParaGard, which contains copper and damages sperm. Now there’s even a “short term” IUD option (one that lasts for 3 years) that’s specifically marketed to young women without children. As the gap widens between the ages of first sexual intercourse and first child—those ages, respectively, are now close to 18 and 25 on average in the US, Kavanaugh says—women need to think more long-term about their birth-control options.

“It’s an increasing period of time where American women want to be protected from pregnancy,” Kavanaugh says, “and IUDs work perfectly for that window. The recognition of that fact has been a big step for the re-adoption of IUDs in the US.” Use of long acting reversible contraception—IUDs and implants—rose from 2.4% in 2002 to 8.5% in 2009. Most of that increase was due to IUDs. “We expect that usage to keep going up,” Kavanaugh says.

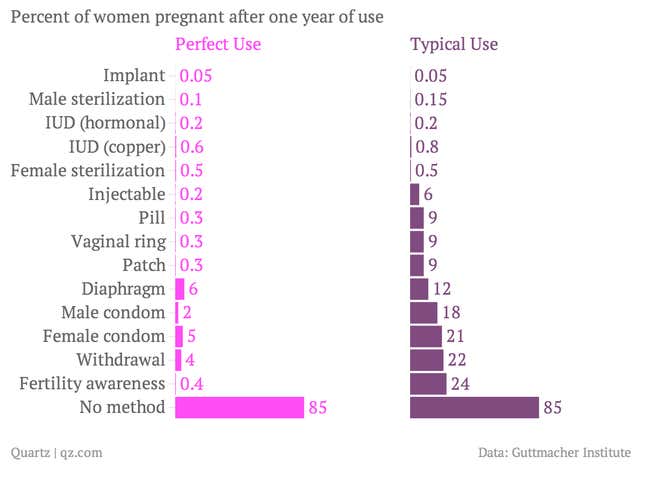

IUDs are effectively the most foolproof method of birth control, excluding abstinence and permanent sterilization. This is because the device is put in place and left there until it needs to be replaced, so there’s no room for mistakes by the patient.

IUDs are environmentally friendly, too—more so than any method other than permanent sterilization, according to a recent analysis by Alexandra Ossola of Scienceline.org. Condoms make waste, and pills put hormones into the water supply. Each IUD lasts from three to 12 years, depending on the type (longer than previously thought, according to a recent study), so you get a lot of use out of a very small amount of plastic and metal.

The main drawback of IUDs is they cost a lot upfront. A 2012 Mother Jones article reported that a Mirena costs $843.60 before insertion. A recent study confirmed that, when given counseling and offered any contraception free of charge, more than half of women selected an IUD. “Since the cost is prohibitive for some,” Kavanaugh says, “I think we’ll see an increase in use with the Affordable Care Act.” The act, which took effect last fall, makes contraceptive coverage mandatory for all insured women.

The US Supreme Court is, however, now hearing arguments in two cases that challenge this mandatory coverage, and they might slow the US’s adoption of IUDs. Hobby Lobby Stores and Conestoga Wood Specialties are two companies fighting, on religious grounds, for the right not to have to give employees birth-control coverage that “ends human life after conception.” Because IUDs can sometimes prevent a fertilized egg from becoming a viable pregnancy, they argue that this method—along with emergency contraception like Plan B—should be exempt. US women are just becoming reacquainted with the IUD after decades of misunderstanding and distrust, and taking away their newfound right to get them for free could set the country back all over again.