Being a non-executive director is a pretty cushy job. Although stricter laws have heaped more responsibility (and liability) on these board members, they still earn $250,000 for attending eight meetings per year, according to the latest numbers for large listed companies in the US. Nice work if you can get it.

But a board packed with retirees riding the gravy train—the average director in the US is 63 years old—isn’t of much use to a company, or its shareholders. Of course, a certain amount of experience is expected of board members, who offer independent strategic advice and approve big company decisions. But directors who stick around for too long can become beholden to management, offering a rubber stamp instead of wise counsel.

Recruitment firm Spencer Stuart recently looked at a large sample of American firms in search of a link between director tenure and company performance (pdf). It concluded that companies with industry-beating market returns swapped out an average of about one director every year. (Technically speaking, the optimal turnover was three to four directors over a rolling three-year period.)

The worst-performing companies refreshed their board the least often, according to Spencer Stuart. Indeed, a recent survey of directors by PricewaterhouseCoopers found that 35% of board members thought that at least one of their colleagues should get the boot, with “aging” one of the top reasons cited.

How long is too long?

Sterling Huang of the Insead business school in France has also studied what he calls “zombie boards.” Isolating director tenure from other factors in a sample of US-listed firms, he found that nine years was the ideal stint for an independent director. This, the data showed, was the average tenure associated with the best performing companies in terms of market value.

As it happens, the average tenure of a non-executive director at an S&P 500 company is currently just under nine years, according to Spencer Stuart. And there are nine independent directors on the average board, so if staggered correctly companies can swap one out per year, as the research suggests they should.

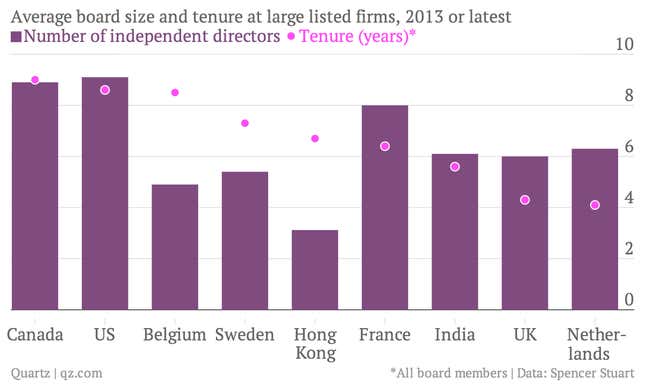

There are no laws limiting director tenure in the US, but not all investors and regulators are comfortable leaving this to firms to decide for themselves—after all, some “independent” directors in Huang’s sample had served for more than 30 years. Many countries in Europe and Asia require companies to justify retaining independent directors beyond a certain time limit with special disclosures and shareholder votes, imposing extra costs and opening them up to shareholder criticism. As a result, the average size and tenure of boards varies widely across countries, as the chart above shows.

Companies will always quibble about specific term limits and quotas, but the research is clear—a board member’s usefulness follows an inverted “U” shape over time. Directors need time, but companies should be wary of letting them get too comfortable.