With the world set to have 9.5 billion people to feed by 2050, the name of the game is productivity. That’s why honeybees are so important—39 of the world’s 57 major crops yield more when bees pollinate them (pdf). And over the last half-century, those crops have assumed a bigger and bigger role in diets all over the world.

It’s also why the eerie die-off of American bees, which has put $30 billion of crops at risk, is so scary. Fortunately, things are better in many countries across the Atlantic, where new research by the European Commission shows “acceptable” mortality rates—meaning less than 10%—at nearly half of the European Union’s bee colonies, compared with 31% mortality rates during the same period in the US.

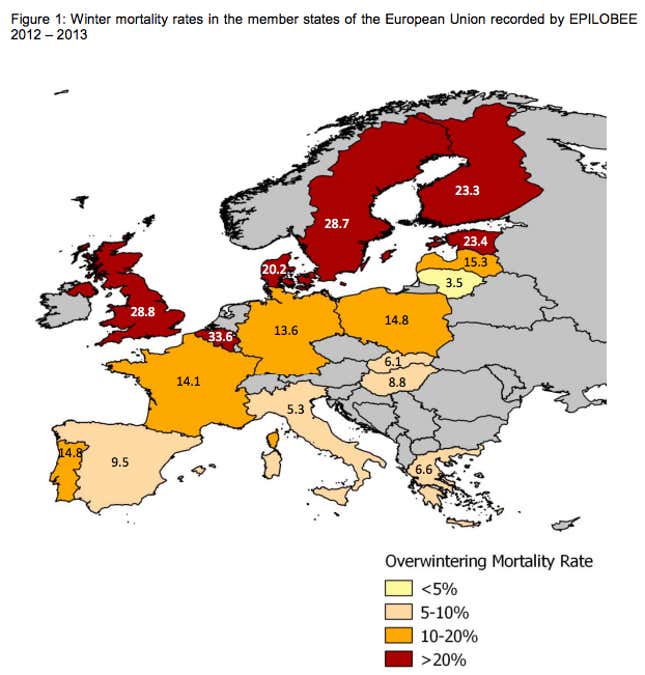

But not in all countries. At one-third of EU bee colonies, winter mortality rates exceeded the 10% level, according to the report (and bear in mind that 20% of EU colonies weren’t surveyed). Northern countries are taking the biggest hit. For instance, colony mortality was as high as 33.6% and 28.8% in Belgium and the UK, respectively.

As always, it’s hard to tell what’s killing the bees. The study, a pilot project investigating 32,000 colonies from 2012 to 2013, focused mainly on gathering data for future analysis.

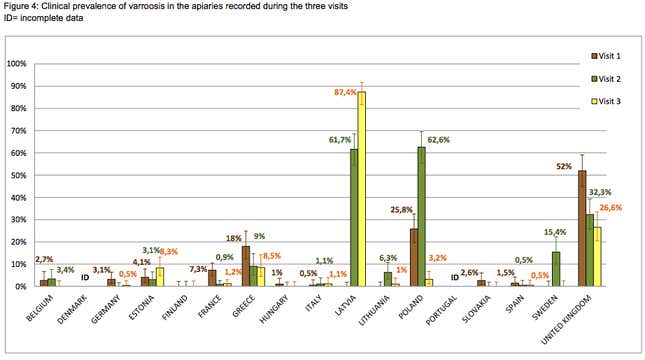

One possible culprit is simply the unusually harsh winter of 2012-13 in Europe. On a positive note, the study established that foulbrood disease, a deadly bacterial outbreak that’s ravaged American colonies, isn’t an immediate threat. However, the report did note a worrying prevalence of Varroa destructor—a virulent parasite that likely contributed to colony collapse disorder in Canada and Hawaii—in bee colonies in Latvia, the UK and Poland.

But the report didn’t examine the impact of pesticides or biodiversity. Though the EU has among the strictest laws against the use of potentially harmful pesticides, research on bee die-offs to date reveals just how little we understand about the complex interplay of pesticides, fungicides and parasites and their impact on bee immune systems.

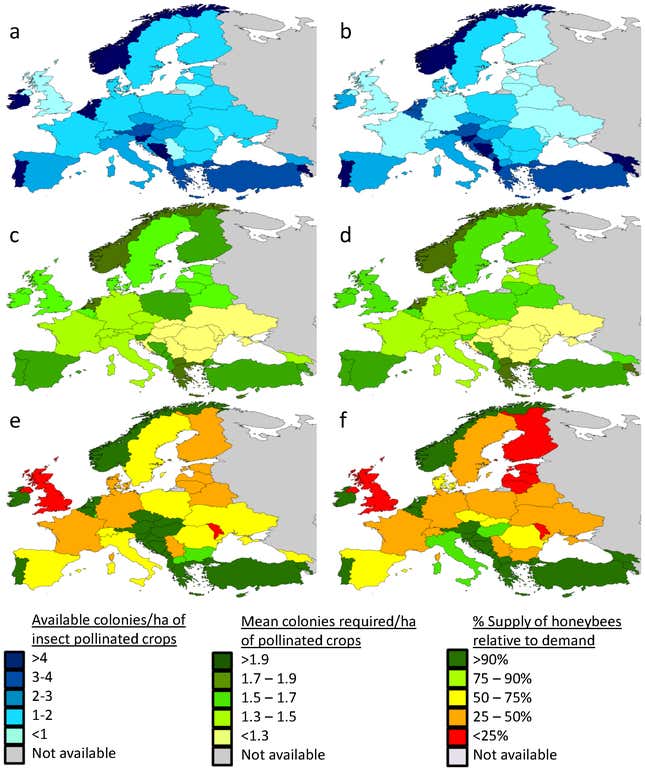

What we do know is that European farmers need bees more than ever. Despite rising numbers of EU colonies, pollination demand is accelerating at a brisker clip, growing 4.9 times faster than available stocks, according to a recent study in PLOS ONE. The UK, for example, has only one-quarter of the honeybees it needs.

That’s happening thanks largely to a surge in biofuel feed crops like sunflowers and soybeans. An EU directive mandates that by 2020, 10% of transport fuel used by member countries must come from renewable sources, such as oil from seeds and beans.

So if bees are dying at scary rates in northern Europe, at the same time as biofuel production is expanding, how is anything getting pollinated? Wild bees are likely filling the gap. As the BBC reports, wild pollinators do work that would cost British farmers £1.8 billion ($3 billion) to do themselves.

However, as the European Commission’s report noted, current indicators of wild bee populations “show a worrying decline.” A recent bumblebee assessment found that nearly a quarter of Europe’s 68 bumblebee species are threatened with extinction, said the commission. As the BBC points out, that could be putting crops in the UK and other EU countries at more risk than farmers realize.