In technology, it’s sometimes good to let a pioneer figure out the pitfalls of a new market. Apple’s iPod transformed music listening after countless lesser MP3 players failed to make a real dent.

Google is now trying to do something similar in cloud computing. The company last month announced price cuts that made its cloud services cheaper than Amazon’s, the leader in cloud services for businesses. At almost the same time, Google orchestrated a flurry of coverage of its cloud services.

But whereas music players were a fragmented industry when the iPod appeared, in cloud computing Google is playing catch-up with a single market leader, Amazon, that has a track record of destroying incumbents in every industry it gets into. What Google has in its favor, besides a sheer technical expertise, is that it already runs the biggest cloud-computing operation in the world—just that it puts most of it to a different use. The resulting battle is likely to be epic, and its outcome determines nothing less than who will control the internet.

The cloud is already massive and growing even bigger

“The cloud” is a term so nebulous it hardly does justice to the specifics of Google’s and Amazon’s respective strategies. Generically, the cloud is just a vast mass of computers connected to the internet, on which people or companies can rent processing power or data storage as they need it. It’s used for everything from hosting websites to storing archives to running massive data-crunching operations.

Unless you work in technology or corporate logistics, you might not have known that Amazon was ahead of Google in the cloud business. Most consumers will have encountered the cloud in the form of services where Google is strong—email (Gmail), document storage (Google Drive), and the like. But Amazon Web Services has for years been the front-runner in the business of renting computer power to companies.

To understand the scale of the war brewing between them, it helps to understand that what Amazon and Google are really contesting is who gets to eat a bigger portion of the total corporate information-technology pie. All the warehouses of servers that run the whole of the internet, all the software used by companies the world over, and all the other IT services companies hire others to provide, or which they provide internally, will be worth some $1.4 trillion in 2014, according to Gartner Research—some six times Google and Amazon’s combined annual revenue last year. Not surprisingly, both companies have said at one point or another that this new revenue stream has the potential to be larger than all their current sources of income.

But wait, you say; that stuff isn’t all in the cloud. Most IT services are still provided much closer to where they are used, on PCs themselves or in “private clouds” run by companies and their contractors. (For example, IDC reports that only 13% of companies’ data is currently stored in the cloud.) But if the advocates of cloud computing are right, some day most of that spending will be on software that runs on remote computers controlled by internet giants.

When that time comes, all the world’s business IT needs will be delivered as a service, like electricity; you won’t much care where it was generated, as long as the supply is reliable. And Google and Amazon both want to be the utility company that provides it—minus the government regulation that usually attends utilities.

For once, Google is David to someone’s Goliath…

In response to Google’s price cuts last month, Amazon fought back with price cuts of its own, leaving the two companies’ services more or less at parity with each other in terms of cost, if not performance.

There’s a problem with Google’s cloud push, however: It arrives eight years too late. Way back in 2006, Amazon had the foresight to start renting out portions of its own, already substantial cloud—the data centers on which it was running Amazon.com—to startups that wanted to pay for servers by the hour, instead of renting them individually, as was typical at the time.

Because Amazon was so early, and so aggressive—it has lowered prices for its cloud services 42 times since first unveiling them, according to the company—it first defined and then swallowed whole the market for cloud computing and storage.

…and Amazon’s lead over Google is almost unfathomably big

Today the cloud market has many players. Yet if Amazon’s entire public cloud were a single computer, it would have five times more capacity than those of its next biggest 14 competitors—including Google—combined. Every day, one-third of people who use the internet visit a site or use a service running on Amazon’s cloud. (Netflix runs on it almost entirely.) That’s one reason why, when a portion of Amazon’s cloud goes down, it can seem like the entire internet has failed.

Analysts have called Amazon the “Walmart of the cloud” for its rock-bottom prices and just-good-enough service. But there’s also a very human reason why Amazon has become so dominant. It’s the same reason Microsoft was able to win so many corporate contracts during the heyday of the Windows PC.

Amazon authored the lingua franca of the cloud…

For you to use a cloud service, your own computer has to swap information with the servers in the cloud. That means they need a common language, since computers all have different versions of operating systems and software. When the cloud started, there was no such common language. So Amazon created one of its own—in technical terms, an application programming interface, or API.

By now companies that rely heavily on cloud services are almost all customers of Amazon. (There are a handful of notable exceptions like the photo-sharing app Snapchat, which is on Google’s cloud.) That means they have created enormous libraries of code that are designed to talk to Amazon’s API. Efforts to create a universal cloud-computing language—the most prominent is called OpenStack—aren’t doing so well.

Which means Amazon has, by default, defined the language of the cloud.

“I claim that Amazon Web Services is the Windows of today,” says Mårten Mickos, CEO of Eucalyptus, which helps companies build “private clouds” (i.e., servers and data centers they own and physically control) that can interface with Amazon’s public cloud. What he means is that Amazon’s cloud has become so dominant, and so popular with developers—who are only human and therefore generally loath to learn new technologies, even if they’re in some ways superior—that its position resembles that of Microsoft Windows at its zenith. “Amazon has the chance of controlling the public cloud just like Windows controlled the PC environment for a long time,” he adds.

Amazon’s cloud service now claims hundreds of thousands of customers, says Mickos, so at a minimum there are hundreds of thousands of developers adept at the company’s more than 38 different cloud services, which range from everyday computing and storage to systems for making sure that customer’s services stay up even when one of the regional data centers that comprise Amazon’s cloud (inevitably) goes down.

…it has big customers like Netflix locked in…

What’s it like to be one of the hundreds of thousands of customers for Amazon’s cloud? Like all relationships with technology, it has a touch of Stockholm Syndrome.

Ariel Tseitlin, head of cloud at Netflix, told Fast Company that as an early customer of Amazon Web Services, Netflix had to pay a “large pioneer tax” in order to make the service work for Netflix. That included a big push to write open-source code that stitches together bits of Amazon’s cloud in ways that are useful to Netflix and Amazon’s other customers.

As a result, said Tseitlin, “we don’t have a particularly strong desire to pay that pioneer tax again with another cloud provider.”

In other words, Netflix would pay a high cost in switching to a competitor. Not just a financial cost; it would also just be a huge hassle, a company-sized version of the headache of switching from a PC to a Mac, or from an iPhone to an Android smartphone, or learning to drive on the opposite side of the road. Technology can move quickly, but when it does, the technology between our is ears slow to adapt.

…and even as Google plays catch-up, Amazon is pressing ahead

One reason Amazon’s cloud service grew so fast was its cheapness. For literally the price of a cup of coffee, developers could massively boost their processing power and storage for a day to deal with a short-term problem, meaning they never had to worry about budgeting bureaucracy. Google is now trying to undercut even those prices, but in the past few years the game has somewhat changed.

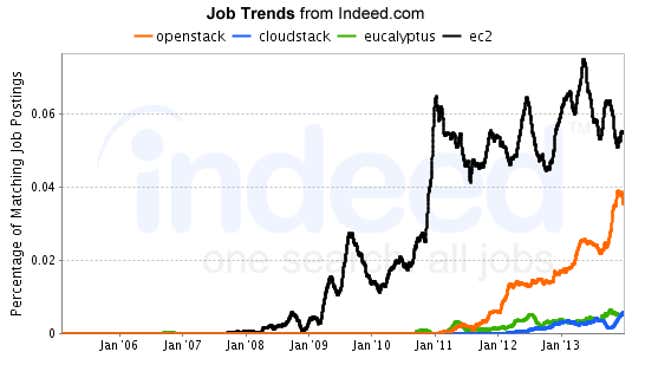

Offering cheap cloud will still help Google nab startups where developers have enough sway to decide which provider to use. (That’s one reason Google’s cloud got Snapchat, along with all its explosive growth.) But for bigger companies, a key consideration isn’t how a much a cloud service costs, but how easy it is to hire engineers who can write software in the language of that cloud service. In that area, Amazon is far ahead of all competitors. A search of jobs website Indeed.com puts listings for Amazon’s primary cloud technology, called EC2, far ahead of competing languages for communicating with the cloud:

Amazon’s cloud services have so much momentum that the company could just rest on its laurels. Its revenue in cloud services was an estimated $3.4 billion in 2013. But the company is continuing to roll out new services even as it keeps pace with Google in the price war. “I think Amazon is now trying to expand even faster while they have the freedom to expand,” says Mickos.

Google does have a long game: superior technology…

Perhaps the most telling evidence of Amazon’s advantage is that Google’s cloud API is in fact very similar to Amazon’s, says Mickos. It seems to have accepted that Amazon’s API is what engineers are comfortable with.

But similar doesn’t mean compatible. “Running services on both Amazon and Google and switching between them, the cost of it is high—you have to maintain a lot of ‘glue code’,” says Mickos—meaning custom-written software that allows workloads and data to flow between the two companies’ clouds. “That’s heavy and expensive and fraught with problems.” That means any given company is likely to use just one provider for all its cloud needs.

As long as Amazon is willing to match Google on price—which it has, so far—Google’s only alternative is to beat Amazon at the technology. The only reason that might be possible is that, even though Amazon’s external cloud business is much bigger than Google’s, Google still has the biggest total cloud infrastructure—the most servers and data centers. That’s because Google itself uses so much cloud computing power for Google Search, Gmail, and all the other services it provides. Given Google’s near-legendary ability to attract and retain talent, Amazon’s cloud team is now in a fight with the only engineers in the room who might be smarter than them—and have more resources.

…and enormous investments in infrastructure

Google has already laid extra fiber-optic cable all over the globe, to tie its data centers to each other and to customers with ultra-fast connections. But Amazon is doing the same—and both companies are customizing and optimizing every single part of their cloud infrastructure, from servers down to the electric substations that power them.

Right now, tests of Amazon’s and Google’s clouds show that by one measure at least—how fast data is transferred from one virtual computer to another inside the cloud—Google’s cloud is seven to nine times faster than Amazon’s. (Update: A more recent test by the same tester, David Mytton of Server Density, found the two more evenly matched.) This is just one measure, however, and only makes a difference to certain customers. What will ultimately matter is the overall experience developers and corporations have when playing in each cloud.

Ironically, however, the end point of the technological arms race between Google and Amazon will, at least for some types of services, be clouds that customers don’t much think about, the same way we don’t often think about where our electricity comes from—it’s just there. Netflix’s Tseitlin told Fast Company that he longs for the day when the cloud is a commodity that can be taken for granted.

But we aren’t there yet. “It really isn’t a utility like we feel someday it is going to become,” he said.

But why compete if the cost of cloud computing is heading to $0?

The prospect of becoming a utility could be worrying for Google and Amazon, though. Consumers can already store gigabytes of information for free with services like Google Drive and Dropbox. It won’t be long before it costs nothing to store pretty much your whole life in the cloud. Businesses are another matter—they have many orders of magnitude more data—but all the same, as hardware gets cheaper and giants like Amazon and Google come up with ever more efficient ways to use it, merely renting out data storage and processing power will become a commodity business with cutthroat margins.

That means both companies are developing more sophisticated services that will also lock customers in to their cloud-storage systems. Amazon has Redshift, a “data warehouse service” which allows businesses to analyze gigantic quantities of data, and in turn creates more demand for the underlying cloud storage. Google has its services like Google App Engine, which makes it easier for developers to build entire applications with Google’s own libraries of code—which, of course, must then be run in Google’s cloud.

But even with add-ons like these, and even if, as Google and Amazon claim, cloud computing ends up being even bigger for them than their existing businesses, that’s no guarantee of how profitable it will be. Which means that the battle for the cloud is either the world’s biggest battle of egos—not unheard of in Silicon Valley—or it’s ultimately about something else, like control.

The future is Amazon, Google, Microsoft… and not much else

Whatever the endgame, it could take decades to reach. In the meantime, this is a fight that rewards scale. Size means efficiency, efficiency means lower prices, and smaller providers of cloud services are going to have a hard time competing.

And there’s a third big player: Microsoft. The company launched its own cloud service, Azure, in 2008. Though Azure is an also-ran for now, the company is so deeply entrenched in corporate IT culture that at least some companies are willing to wait for it to bring its cloud services to parity with Amazon’s. And like both its main rivals, Microsoft has the money to spend on the engineers and infrastructure required to make its cloud truly big.

“I do think the market [for cloud services] will support three big players,” says Mickos. “Google and Microsoft will build big businesses but can’t take the lead away from Amazon anytime soon.”

That still leaves room for a gaggle of smaller companies providing other services, such as private clouds for companies that are nervous about keeping their data on someone else’s servers in an age of hacking and NSA surveillance. Companies that offer such services, like Rackspace and VMWare, as well as Mikos’s Eucalyptus, can offer these clients more control over their data—though there is evidence to suggest that private clouds are no more secure than the ones administered by Google and Amazon.

Either way, the upshot of all this competition is that computing has never been cheaper, and it will only become cheaper still. And as the internet penetrates every part of our lives, down to the everyday objects like toasters and cars that will someday soon be “smart” and connected, humanity is only going to need more cloud.