This item has been corrected.

You may never have heard of the southwestern Chinese city of Chongqing, but by some measures it is one of the largest and fastest-growing cities in the world, with an official population of 29 million—about the same as Saudi Arabia—and unofficial population of 32 million or more.

The city center of Chongqing boasts a mere 9 million people, but dozens of satellite districts such as Fuling (population 1 million) and Wanzhou (1.6 million) are each major cities in their own right. In total, Chongqing covers an area the size of Austria, and it’s about to become part of a mega-region that is even larger, part of move in China to create the biggest urban municipalities on Earth.

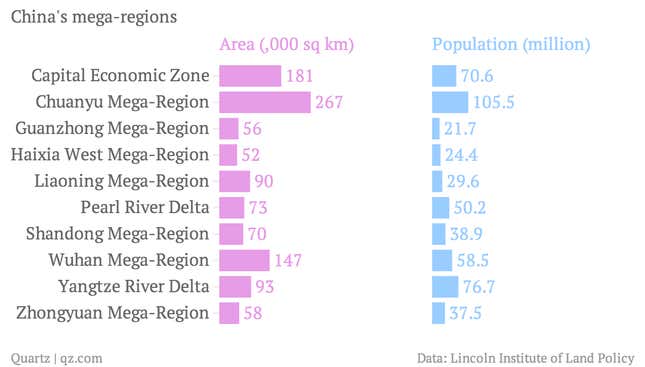

Chongqing, for example, will be part of the even larger Chuanyu mega-region, which also includes the major city of Chengdu and 13 cities from Sichuan province. The Capital Economic Zone encompasses Beijing and Tianjin; the Pearl River Delta region includes Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong; and the Yangtze River Delta region is centered around Shanghai.

China isn’t alone in the development of mega-regions—greater Tokyo and the Washington, DC-Boston corridor also have similarly huge populations and geographies—but China’s ongoing urbanization and rapid growth is making it something of a laboratory for urban planning on a massive scale. The theoretical appeal of ever-larger municipal areas is that they will create efficiencies in the delivery of services like transport and sanitation, while knitting together a thriving urban ecosystem.

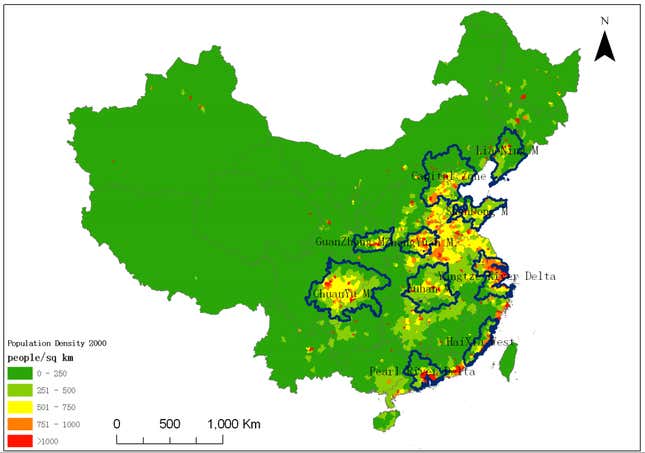

The trouble is that China’s mega-cities and mega-regions aren’t being built with an eye toward maximizing the advantages and minimizing the downsides of creating these massive metropolises. Most importantly, the mega-regions are being built around a small number of city centers, many of which are surrounded by concentric circles of commuters and bedroom communities that makes traffic hellish and pollution even worse.

“Among the 10 developed and emerging mega-regions in China, only a limited number have exhibited a significant level of polycentricity,” concluded a report by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (pdf), a US think tank. “Around half of the 10 mega-regions are either dominated by a single major center, or by a limited number of major centers which are located closely to one another.”

This is a problem because it ultimately means everyone will want to work in close proximity to the city centers, which causes sky-high property prices and transportation headaches. Size doesn’t always have to be a negative, though.

“Mega-cities are a necessary step in the development of urban areas,” Eric Marcuson, a Chongqing-based urban planner at Aecom, told Quartz. “A city is just an urban area with one center, but to increase growth and productivity cities eventually need to encompass more, complimentary centers.”

Unfortunately it doesn’t appear that China is following the advice of urban planners like Marcuson. Take Beijing, a city of around 20 million residents with just one main center for commerce and productivity. It is surrounded by concentric ring roads that create heavy traffic, and even its very good subway system is hugely overcrowded. Nevertheless, the Chinese government seems determined to double-down on Beijing, combining it with the city of Tianjin and parts of Hebei province into one huge megalopolis. But as Quartz has reported, While Hebei isn’t likely to attract workers away from Beijing, the other cities in the proposed “Jing-Jin-Ji” region are mostly suburbs, with no real urban centers of their own—precisely the opposite to what the specialists advise.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly named the Chongqing-based urban planner as Eric Marcusson instead of Eric Marcuson.