When the first Harry Potter movie came out in 2001 the idea of the Daily Prophet, a newspaper that contains moving pictures, qualified as magic. A Kickstarter campaign by Ynvisible, a Lisbon-based technology firm, is bringing that magic to life with its displays, held together with paper-thin circuitry.

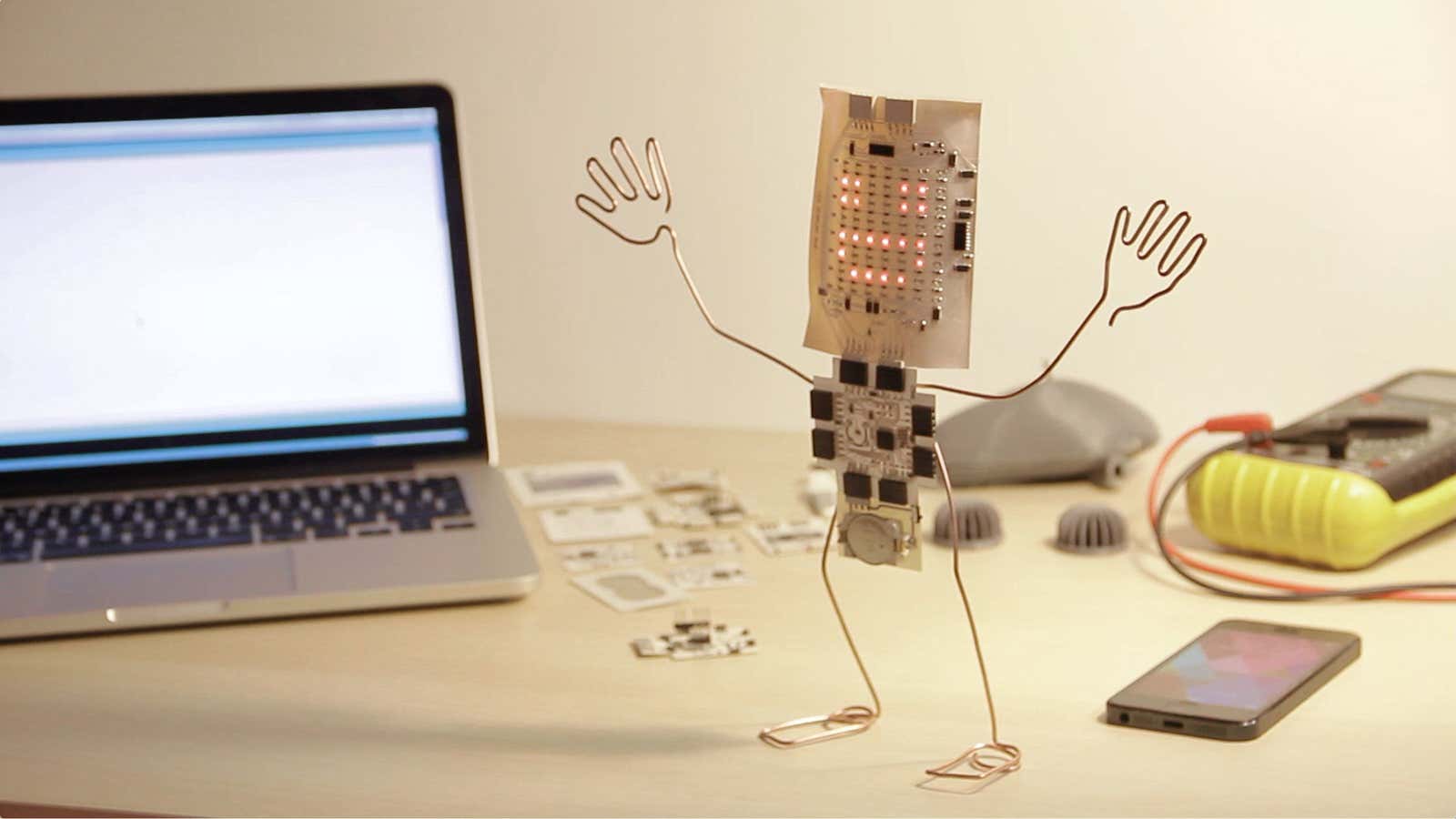

Ynvisible’s offering, called Printoo, is a bunch of paper-thin circuit boards. Imagine the Arduino board, perhaps the most popular do-it-yourself micro-controller used by tinkerers, but thinner and lighter. The Printoo modules are flexible, meaning they can be bent, folded and attached to any object—cans, clothes, toys—and come with both LEDs as well as flat, flexible “electrochromatic” displays for output. The idea obviously caught the imagination of the DIY community. The Printoo Kickstarter achieved its goal of $20,000 within four days of going live. It has exceed $31,000 at the time of this writing, with another 24 days before it closes.

Printable, or flexible, electronics have been around for years, but have never taken off in mainstream consumer goods, with the notable exception of the Duracell battery power tester. Several companies, including the Scandinavian Thinfilm and American Soligie, make products for a narrow range of customers—security professionals, medical researchers, logistics. Ynvisible itself has been in printable electronics since 2006, and has served a small range of corporate customers, such as L’oreal. The industry is tiny. Xerox PARC estimates the global market for printable electronics is just $1 billion.

“I wouldn’t say there is yet a clear success case in the industry,” says Ynvisible product manager Manuel Camara. The idea behind the Kickstarter campaign, therefore, was to bring the technology to early adopters so they could figure out wider applications for it. And the company intentionally set a low goal—Ynvisible assumed research and investment as internal costs—to encourage its success.

To make Printoo familiar, Camara and his team adapted it to work with Arduino, which hobbyists have used to make everything from Twitter-enabled coffee pots to shoelaces that tie themselves. That meant compromising on flatness—Arduino connectors are pretty chunky relative to thin film, but gives it much greater versatility and ease of use. Camara says Ynvisible’s “vision” is to “bring everyday objects to life.” For that to happen, it isn’t just processing power that needs to get cheaper and smaller, which it has, but the input and output mechanisms also need to be smaller and easily adaptable. Ynvisible is betting there is a broad market for such technology. The roaring success of its Kickstarter campaign is an early validation of that belief.