It’s now 20 years since Steve Albini, the legendary rock music producer best known for Nirvana’s last studio album In Utero, penned a seminal essay for the literary magazine, The Baffler.

It was titled “The Problem with Music,” and detailed how the entire food chain of the music business was set up to profit from the end product, except for the artists who actually conceived and made it.

He offered the example of a band, “pretty ordinary, but they’re also pretty good” that signed to a moderately sized independent label. They sold 250,000 copies of an album—considerable success by most standards—making the music industry more than $3 million, yet still ending up $14,000 in debt. “The band members have each earned about 1/3 as much as they would working at a 7-11, but they got to ride in a tour bus for a month,” he famously wrote.

Many aspiring musicians (and music journalists) of a certain vintage would have come across this inspirational piece of writing, thanks largely to the internet. So it’s quite fitting that since then, the same irrepressible force—the internet—has largely dismantled the profit centers the music industry has relied on for most of its existence.

Not everyone is cool with that. “The internet will suck the creative content out of the whole world until nothing is left,” wrote David Byrne, the former Talking Heads frontman, a sentiment that is shared by many in the music business who think the economics for artists have gotten even worse. Yet Albini, who we tracked down to discuss the state of the industry, is relatively upbeat, ebullient even.

“The single best thing that has happened in my lifetime in music, after punk rock, is being able to share music, globally for free,” he tells Quartz. “That’s such an incredible development.”

Over the past two decades the way recorded music is consumed has changed irrevocably. Napster and the various copycat file sharing services it spawned taught an entire generation of would-be CD buyers to expect to be able to listen to their favorite music for free. Not long after, Apple’s iTunes made it more attractive for those who are prepared to pay for music to buy individual songs rather than full albums.

The adjustment to this new reality has been painful, and not everyone has embraced it. (Remember when Jon Bon Jovi, hilariously, blamed Steve Jobs for the death of the music business?) But in Albini’s view, what exists now is far better than what existed before.

“Record labels, which used to have complete control, are essentially irrelevant ,” he says. ”The process of a band exposing itself to the world is extremely democratic and there are no barriers. Music is no longer a commodity, it’s an environment, or atmospheric element. Consumers have much more choice and you see people indulging in the specificity of their tastes dramatically more. They only bother with music they like.”

In the physical music era, company executives and the music press were the arbiters of taste— a band needed to convince a label to sign it, fund it, and often get critics to like it, to have a realistic shot at success. These days, it’s a much more meritocratic process: people can make music in their garage and reach their audiences through YouTube, BandCamp and any number of internet avenues. “You can literally have a worldwide audience for your music….with no corporate participation, which is tremendous,” Albini says.

Swimming upstream

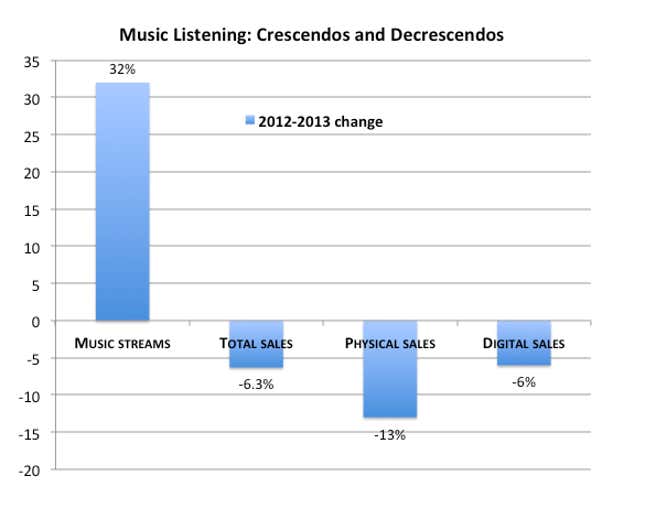

Another seismic internet-driven shift in music consumption is currently underway, with streaming services like Pandora (a publicly listed company with a market value of around $5 billion) and Spotify (valued at $4 billion in the private markets ahead of a possible IPO) becoming increasingly popular, and arguably responsible for further declines in recorded music sales.

Albini these days runs his own recording studio in Chicago and is lukewarm on the value of such services for true music enthusiasts. He’s skeptical about the chances of them becoming a viable earnings stream for artists, but refreshingly comfortable with their business models.

“I think they are extremely convenient for people who aren’t genuine music fans, who don’t want to do any legwork in finding bands,” Albini says. “[But] I think there is incorrect calculus being done by the people who are upset about them.” When a song is played one million times on Spotify, it can still have an audience of one person who plays it a lot. When it is played one million times on terrestrial radio, the audience is orders of magnitude bigger, he explains. “I actually think the compensation is not as preposterous as anyone else,” he says. “It’s like complaining that cars are going faster than horses.”

Spotify, which is reportedly part-owned by record labels, has been subject to fierce and colorful criticism from artists about remuneration. But Pandora, a much bigger service, has had its biggest problems with music publishing companies who control licensing rights and collect royalties for songs used commercially (for example by radio stations, digital music services, film studios and advertisers.)

Albini describes the music publishing business as “extortionate.” “Publishing was a racket. It was not a legitimate part of the music business,” he says. We recently took a deep dive into a court case between Pandora and the century-old American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) that uncovered some questionable behavior by the music establishment against the internet company. The Future of Music Coalition also has an explainer on how the incredibly complex world of music royalties works here. “It never operated for the benefit of songwriters,” says Albini. “Of all of the things that have collapsed in the music paradigm, the one I am most pleased to see collapse is the publishing racket.”

The future of music

It’s not just record company profits and shady A&R executives that have lost out from the internet-driven disruption of the music industry. The entire ecosystem that once supported musicians—neighborhood record stores, small recording studios like Albini’s Electrical Audio complex in Chicago, and indie record labels—is struggling. Albini likens these players, himself included, to blacksmiths that are surviving on a “thrifty entrepreneurial spirit” and settling into a niche role for really high-quality work.

Yet, amid the collapse of the old music business model, the underlying economics for artists have quietly undergone a significant transformation. Ticket prices for live music have increased significantly. Arguably, this reflects the fact in that our internet-connected, device obsessed society, people are increasingly seeking out tangible experiences. It ultimately means that live performances are likely to be the main way successful artists starting out today will earn their living. “I think that’s a totally much more direct and genuine way for an audience to pay for a band, and a much more efficient means of compensation” Albini says.

“On balance, the things that have happened because of the internet have been tremendously good for bands and audiences, but really bad for businesses that are not part of that network, the people who are siphoning money out. I don’t give a fuck about those people.”