China’s Great Firewall, the government’s censorship program, came down quickly and heavily after a New York Times story on Oct. 25 revealed that family members of Chinese premier Wen Jiabao have made at least $2.7 billion through sectors he has some authority over.

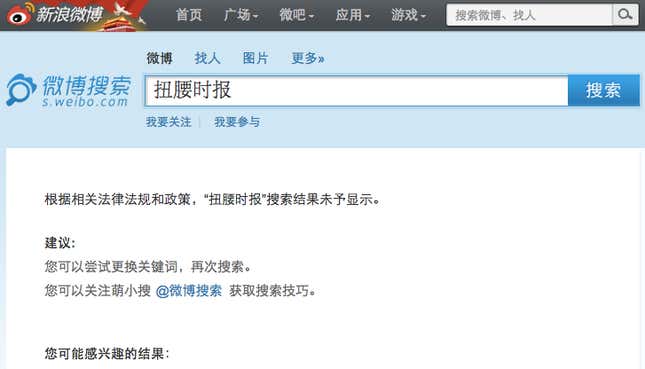

Beijing has said the report was intended to “smear China” and had ulterior motives, but authorities still blocked the paper’s website and all search terms in Chinese related to the story. On Chinese microblogging site Sina Weibo, searches for Wen’s name in Chinese and English have both been blocked as well as “WJB” and “Diamond Wen” or 钻溫. Quartz was also blocked from posting our Chinese translation of the story on Sina Weibo.

Because of China’s upcoming leadership change in November, authorities are more sensitive to stories about Chinese officials, says Sarah Cook, a senior analyst with Freedom House which works on media freedom issues. The government has been hit by political scandals that suggest corruption and subterfuge at the top levels of China’s Communist Party such as the murder of a British businessman committed by the wife of ex-Chongqing party chief Bo Xilai, who allegedly attempted to cover up the case. Another top official’s son crashed and died in a Ferrari outside of Beijing, raising questions about the wealth of officials. ”Part of what is happening here is that the censors both in government and in private firms are on high alert because of the upcoming Party congress,” Cook told me.

To evade the censorship, some Chinese internet users are resorting to creative phrases that haven’t yet been blocked. Like these:

牛约时报 or “Cattle Times”

Chinese bloggers have been using various homonyms for the New York Times to get by the censors. One that translates to “twisted waist times” (扭腰时报) and sounds like the Chinese name for the paper has already been blocked. But “Cattle Times,” another homonym, seems to have gotten through for now.

A user by the name _xiang_long started a post with the term “ni ma,” which literally translates to a Tibetan county but is a reference to “cao ni ma” or “grass mud horse,” to symbolize flouting Chinese censors. “Nyima, ‘Cattle Times’ is now a sensitive term!” he wrote. A blogger by the name of fenghanjianke responded, “People with money are just different.” Another wrote in English, “truth always under the cover.”

The term “18th Party Congress,” a meeting in November where the new members of China’s decision-making Politburo Standing Committee will be announced, is blocked on Sina Weibo. Bloggers use terms like “Sparta” or 斯巴达, characters that sound like the abbreviation for the 18th congress, instead.

某家族 or “a certain family”

There were over 30,000 posts containing the term “a certain family” but only about dozen of the most recent posts were about the New York Times story, a sign that censors may have already deleted messages. Cook said the Chinese government as well as private companies use tens of thousands of human censors to identify and delete social media posts. In one study of almost 1,400 Chinese blog-hosting and bulletin-board platforms, researchers estimated that 13% of posts were deleted, many within 24 hours of a particular term becoming sensitive.

Still, some bloggers thought the netizens were not giving Wen’s family wealth the attention it deserved. One Sina user demanded, “Why isn’t anyone talking about the Cattle Times story that a certain family made $2.7 billion off of the people’s blood sweat and tears?” Others got around the censors by uploading a PDF of the New York Times graphic tracing the family connections. One user advised that it could be downloaded without going around what he casually called “the wall.”

Some Chinese bloggers expressed disappointment in Wen, nicknamed “Grandpa Wen” or the “People’s Premier,” for his reputation as a reformist who cares about China’s lower classes. A user by the name xiaoying0822 said he had heard from foreign media that “some grandpa’s family had made it rich.” He writes, “The fact that we can’t see this from inside China just adds to a loss in faith in the future of this land.”

Another blogger wrote, more ominously, “This certain family’s wealth really allows the country to see how China’s stability will break apart. We’ll wait for tomorrow’s fall.”