Pfizer, the US pharmaceutical giant, has made a $100 billion cash-and-stock offer to purchase Anglo-Swedish rival AstraZeneca. Is this the best use for that much money?

Perhaps, from a shareholder’s perspective: The goal is to obtain AstraZeneca’s collection of patent-protected cancer drugs, a guaranteed cash cow. As an added bonus, Pfizer can fund the takeover with untaxed foreign revenue and structure the deal as a reverse merger, incorporating the combined group in the UK, which further cuts its American tax bill.

Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies are reliant on patent laws that grant them a time-limited monopoly on their drugs, especially in the US, the world’s largest and most profitable pharmaceutical market. Drugs are much more expensive in the US than other rich nations—by 150% on average, according to the OECD—thanks to Americans’ appetite and ability to buy expensive drugs for niche conditions; strict and sometimes outdated regulatory procedures; and a lack of competition for branded drugs.

Maintaining a monopoly goes against what economists have learned about tuning market forces for maximum prosperity, but we make the otherwise unpalatable trade-off with pharmaceuticals to encourage companies to spend the vast sums it takes to develop life-saving medicines. Pfizer, however, has decided it’s better to plough a big chunk money into buying existing patents instead of funding new research. As a result, society may not be getting the trade-off it was promised.

That’s one reason economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis made the case for abolishing the patent system in 2012—patents can lead companies to fight over existing intellectual property instead of invest in innovation. The economists found that patent protection wasn’t the major advantage pharma firms make it out to be, with more relative importance placed on being first to market, having proper manufacturing infrastructure in place, and effective sales and service efforts.

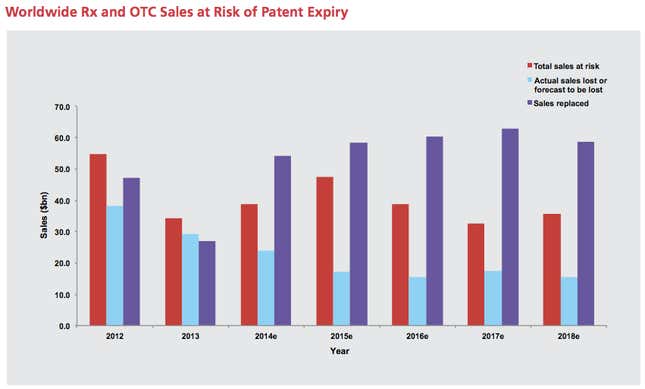

The dreaded “patent cliff” is proving much less daunting these days, with drugmakers employing a variety of tactics to lose only a third of sales of medicines to generic competitors when their patents expire, according to EvaluatePharma. A few years ago these firms routinely lost 70% of a drug’s sales when it lost patent protection.

Pfizer has spent an average of $8 billion on research and development over the past five years, or around 14% of revenue. It keeps nearly $70 billion in cash on its balance sheet outside of the US, which would trigger taxes if it brought it back home. With the AstraZeneca bid, those resources will be used to buy existing drugs, not fund more research. This is despite 2012 being a record a year for new molecule approvals by US regulators and 2013 seeing the highest-ever sales for newly-approved drugs, according to EvaluatePharma.

All of this suggests that the incentives aren’t correctly aligned. Eliminating drug patents is a bit of a blue-sky provocation at the moment, given the industry’s political clout. But reforms to limit patent duration and upgrade America’s aging regulatory infrastructure—a key source of the costs pharma companies face when developing new drugs—could provide better returns to society. Like a good vaccine, injecting a bit more competition won’t kill the pharma industry, but will make it stronger.