Cambodia, where hundreds of thousands of people fled from life under the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, may soon be accepting asylum seekers unwanted by Australia.

The two countries came to a tentative agreement this week that could eventually see some 2,500 asylum-seekers held on Pacific Islands resettled in the Southeast Asian nation. The motivation for the deal largely stems from internal Australian politics, where pressure to protect the country’s many sea borders is high.

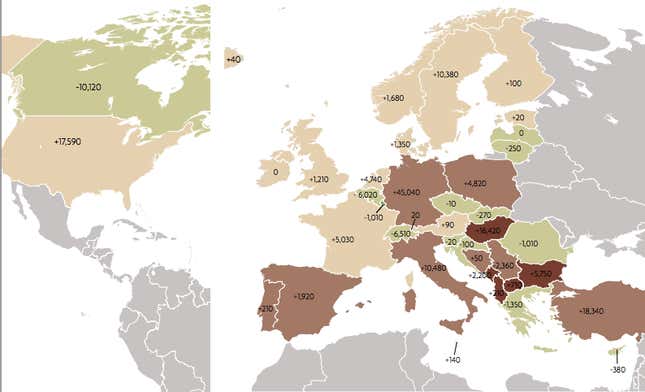

But it also reflects a global trend: the world is seeing a swelling population of refugees who are fleeing to an ever-wider range of countries, where many of them are likely to be only marginally better off—or not better off at all. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, asylum applications increased last year in most of the world:

Cambodia

Australia’s proposal to resettle some of its expanding population of asylum seekers in Cambodia has been roundly criticized by human rights groups.

Out of the top refugee recipient nations last year, Australia saw the largest increase in applications, a jump of 54% to 24,300 claims, according to a report released last month by the United Nations’ refugee agency. In contrast, at the end of 2012, there were only 77 refugees and 24 asylum seekers (pdf) in Cambodia.

Under Canberra’s deal with Phnom Penh, Australia would resettle residents currently living on the islands of Nauru and Papua New Guinea to Cambodia. Cambodia’s foreign ministry says that it is currently reviewing the proposal, and will only accept refugees who voluntarily agree to come to the country.

Human rights groups say that impoverished asylum seekers may be no better off in Cambodia than the countries they fled. The poor Southeast Asian nation ranks 138 out of 186 countries (pdf) on the UN’s Human Development index, which evaluates residents’ standard of living.

Hungary

A member of the European Union (EU) that sits along its eastern border, Hungary has always been a thruway for migration in central Europe, but had never appeared among the world’s top receiving countries for asylum seekers until last year.

Against the backdrop of continuing civil war in Syria, the number of asylum seekers in the country rose six-fold in 2013, to an all-time high of 18,600, according to the UN. Aside from Syrians, applicants are mainly from Russia, Afghanistan and Serbia.

Authorities regularly detain asylum seekers for illegal border entry and, according to Human Rights Watch, the country has been known to send asylum seekers back home despite evidence of ill treatment.

Last year, the country passed new rules to improve the detainment process, but the European Court of Human Rights says detainees are still not informed of their right to challenge detention, and applications for release are rarely granted. Between September 2012 and September 2013, only three out of about 8,000 applications for release from detainment were granted.

Serbia

A country perhaps best known for forcing millions of ethnic Albanians out in the late 1990s has become the 20th largest recipient country of asylum seekers, mainly from Africa and the Middle East. Serbia’s registered asylum claims have jumped from around 52 in 2008 to an all-time high of 5,100 claims in 2013, according to the UN.

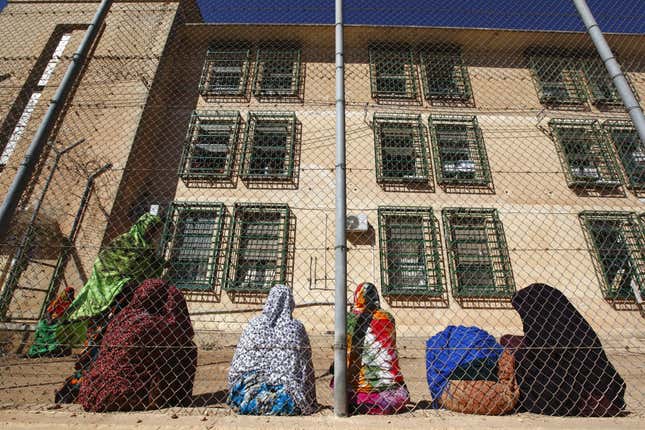

As in Hungary, asylum seekers are often detained in Serbia. Asylum centers in Serbia have been known to fill quickly, forcing hundreds to sleep outside in tents. Migrants are also sometimes sent on to Macedonia and Greece, home to overwhelmed and chaotic asylum systems (pdf), where seekers face the threat of being deported to the countries they escaped from. As of the end of 2012, Macedonia had not granted asylum to anyone since 2008, according to the Center for Research and Policy Making.

Malta

Malta has the highest rate of asylum seekers per its national population of the industrialized world—20.2 per 1,000 inhabitants. (The US and Germany, for comparison, have one and 3.5 asylum seekers per 1,000 inhabitants, respectively.)

Thousands of people from Africa and the Middle East cross the Mediterranean by boat each year in an attempt to reach the EU. Malta rescues many distressed boats, but deems most of these migrants illegal entrants, and places them in detention for up to 18 months.

And while Malta has one of the most efficient asylum-processing systems in Europe, in 2011 only 4% of applicants (pdf, p. 19) were granted refugee protection.