Americans don’t go in for foodownership today, but once upon a time, they did.

Josh Barro at the Upshot has written a provocative case against policies that encourage homeownership over renting. He points out that society doesn’t urge the consumption of food by having people finance and purchase a lifetime’s supply up front, yet it does so for shelter, a similar necessity. In the US, subsidies for homeowners rather than renters have created a huge investor class who benefit when home prices rise. This situation leads to economy-wide distortions ranging from financial crises to artificially high rents in cities.

While Barro’s case against subsidies may be right, there are in fact some good economic arguments for why homeownership is a better choice than renting even in the absence of subsidies. Most come down to the fact that housing is so expensive compared to other goods that it makes sense to minimize transaction costs by living in one place for a long time, incentivize maintenance with owner-occupancy, and reduce financial costs with inflation.

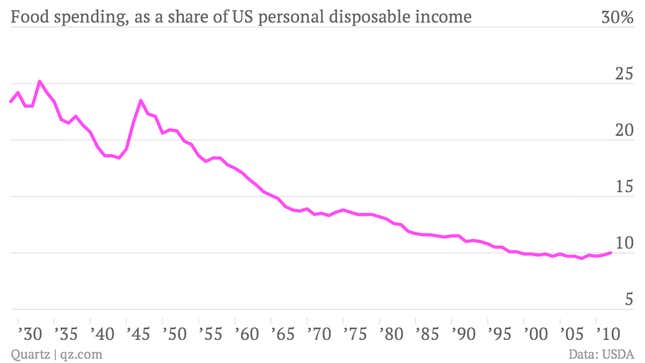

But as it happens, what’s true about housing used to be true about food too. Consider this chart, showing the share of disposable income that Americans have spent on food each year since 1929:

Where food spending was once a quarter of annual income, now it’s less than a tenth, thanks largely to technologies from the tractor to genetically modified seeds that have made agricultural land vastly more productive. When food production was a much larger share of national income before the 20th century, it made sense for many people to be foodowners—that is, to own farms and gain direct access to the goods they spent so much of their income on.

Landowners were foodowners, not homeowners

So the connection between land ownership and prosperity that is so central a part of the American psyche has a lot to do not with the value of the land as property in itself, but with the value of the food grown on that land. America’s 19th-century economic growth was fueled by government subsidies to foodowners—agricultural land was stolen or bought cheaply from natives and given to homesteaders. Being able to live on their own farms would be a double blessing.

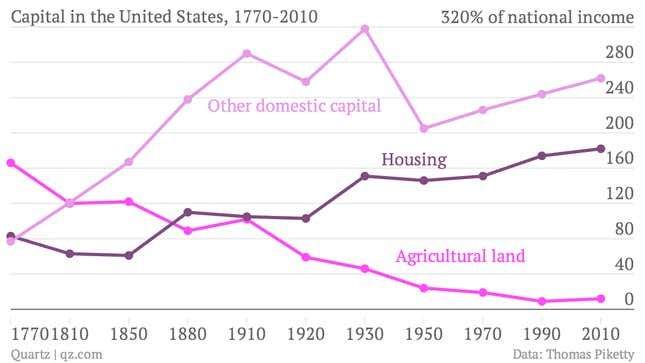

But the economy has changed since the 19th century, and as food costs have fallen, other costs have risen. Today, “affordable” housing is today considered to cost about 30% of disposable income; the typical American family spends more than that. You can see how the transition from the American foodownership society to the American homeownership society played out in national wealth thanks to economist Thomas Piketty’s research. In 1770, agricultural land was the most valuable capital in the US, worth 166% of national income. Today, it’s worth about 12% of national income. Housing, however, has happily replaced it, worth 182% of national income today.

As critics of Piketty point out, however, by separating housing from agricultural land, he’s obscuring a key point that helps explain this change: Land is valued only by its use. What we see in the chart above is that when most of the economy was focused on agriculture, arable land was most valuable, but as the economy switched over to manufacturing and, today, services, land becomes more valuable when it is near lots of people—hence the rise in the value of housing capital. And unlike technologies that made agricultural land more productive in the 20th century, today innovations that allow more people to live on valuable land—like taller buildings and more efficient transit—are limited by the government.

Barro’s certainly right about one thing: Instead of treating housing as a product that we want to make cheaper, like food, we treat it like something we want to get more expensive. That’s why he thinks it would be smart to unbundle subsidies for housing—the shelter people actually need and over-pay for—from subsidies for landownership, a relative luxury in the modern US economy, where land isn’t necessary for personal economic security. Economists think one way to make the situation more efficient would be to tax land separately from the structures built upon it. That could increase investment in property itself—and cut housing costs.