Virtually every country on Earth will be able to build or acquire drones capable of firing missiles within the next ten years. Armed aerial drones will be used for targeted killings, terrorism and the government suppression of civil unrest. What’s worse, say experts, it’s too late for the US to do anything about it.

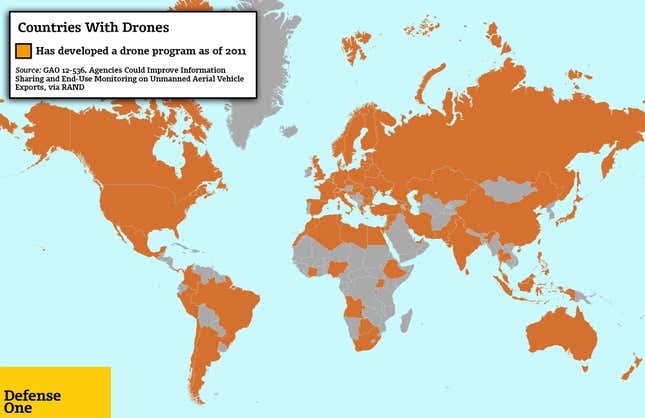

After the past decade’s explosive growth, it may seem that the US is the only country with missile-carrying drones. In fact, the US is losing interest in further developing armed drone technology. The military plans to spend $2.4 billion on unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, in 2015. That’s down considerably from the $5.7 billion that the military requested in the 2013 budget. Other countries, conversely, have shown growing interest in making unmanned robot technology as deadly as possible. Only a handful of countries have armed flying drones today, including the US, UK, Israel, China and (possibly) Iran, Pakistan and Russia. Other countries want them, including South Africa and India. So far, 23 countries have developed or are developing armed drones, according to a recent report from the RAND organization. It’s only a matter of time before the lethal technology spreads, several experts say.

“Once countries like China start exporting these, they’re going to be everywhere really quickly. Within the next 10 years, every country will have these,” Noel Sharkey, a robotics and artificial intelligence professor from the University of Sheffield, told Defense One. “There’s nothing illegal about these unless you use them to attack other countries. Anything you can [legally] do with a fighter jet, you can do with a drone.”

Sam Brannen, who analyzes drones as a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ International Security Program, agreed with the timeline with some caveats. Within five years, he said, every country could have access to the equivalent of an armed UAV, like General Atomics’ Predator, which fires Hellfire missiles. He suggested five to 10 years as a more appropriate date for the global spread of heavier, longer range “hunter-killer” aircraft, like the MQ-9 Reaper. “It’s fair to say that the US is leading now in the state of the art on the high end [UAVs]” such as the RQ-170.

“Any country that has weaponized any aircraft will be able to weaponize a UAV,” said Mary Cummings, Duke University professor and former Navy fighter pilot, in a note of cautious agreement. “While I agree that within 10 years weaponized drones could be part of the inventory of most countries, I think it is premature to say that they will… Such endeavors are expensive [and] require larger UAVs with the payload and range capable of carrying the additional weight, which means they require substantial sophistication in terms of the ground control station.”

Not every country needs to develop an armed UAV program to acquire weaponized drones within a decade. China recently announced that it would be exporting to Saudi Arabia its Wing Loong, a Predator knock-off, a development that heralds the further roboticization of conflict in the Middle East, according to Peter Singer, Brookings fellow and author of Wired For War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century. “You could soon have US and Chinese made drones striking in the same region,” he noted.

Singer cautions that while the US may be trying to wean itself off of armed UAV technology, many more countries are quickly becoming hooked. “What was once viewed as science fiction, and abnormal, is now normal… Nations in NATO that said they would never buy drones, and then said they would never use armed drones, are now saying, ‘Actually, we’re going to buy them.’ We’ve seen the UK, France, and Italy go down that pathway. The other NATO states are right behind,” Singer told Defense One.

Virtually any country, organization or individual could employ low-tech tactics to “weaponize” drones right now. “Not everything is going to be Predator class,” said Singer. “You’ve got a fuzzy line between cruise missiles and drones moving forward. There will be high-end expensive ones and low-end cheaper ones.” The recent use of drone surveillance and even the reported deployment of booby-trapped drones by Hezbollah, Singer said, are examples of do-it-yourself killer UAVs that will permeate the skies in the decade ahead—though more likely in the skies local to their host nation and not over American cities. “Not every nation is going to be able to carry out global strikes,” he said.

Weaponized drones are inevitable: embrace it

So, what option does that leave US policy makers wanting to govern the spread of this technology? Virtually none, say experts. “You’re too late,” said Sharkey, matter-of-factly.

Other experts suggest that its time the US embrace the inevitable and put weaponized drone technology into the hands of additional allies. The US has been relatively constrained in its willingness to sell armed drones, exporting weaponized UAV technology only to the UK, according to a recent white paper, by Brannen for CSIS. In July 2013, Congress approved the sale of up to 16 MQ-9 Reaper UAVs to France, but these would be unarmed.

“If France had possessed and used armed UAVs…when it intervened in Mali to fight the jihadist insurgency Ansar Dine—or if the US had operated them in support or otherwise passed on its capabilities – France would have been helped considerably. Ansar Dine has no air defenses to counter such a UAV threat,” note the authors of the RAND report.

In his paper, Brennan makes the same point more forcefully. “In the midst of this growing global interest, the US has chosen to indefinitely put on hold sales of its most capable [unmanned aerial system] to many of its allies and partners, which has led these countries to seek other suppliers or to begin efforts to indigenously produce the systems,” he writes. “Continued indecision by the US regarding export of this technology will not prevent the spread of these systems.”

The Missile Technology Control Regime, or MTCR, is probably the most important piece of international policy that limits the exchange of drones and is a big reason why more countries don’t have weaponized drone technology. But China never signed onto it. The best way to insure that US armed drones and those of our allies can operate together is to reconsider the way MTCR should apply to drones, Brannen writes.

“US export is unlikely to undermine the MTCR, which faces a larger set of challenges in preventing the proliferation of ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as addressing more problematic [unmanned]-cruise missile hybrids such as so-called loitering munitions (e.g., the Israeli-made Harop),” he writes.

Weaponized, yes. Weaponized and autonomous? Maybe.

The biggest technology challenge in drone development also promises the biggest reward in terms cost savings and functionally: full autonomy. The military is interested in drones that can do more taking off, landing and shooting on their own. UAVs have limited ability to guide themselves and the development of fully autonomous drones is years away. But some recent breakthroughs are beginning to bear fruit. The experimental X-47B, a sizable drone that can fly off of aircraft carriers, “demonstrated that some discrete tasks that are considered extremely difficult when performed by humans can be mastered by machines with relative ease,” Brannen notes.

Less impressed, Sharkey said the US still has time to rethink its drone future. “Don’t go to the next step. Don’t make them fully autonomous. That will proliferate just as quickly and then you are really going to be sunk.”

Others, including Singer, disagreed. “As you talk about this moving forward, the drones that are sold and used are remotely piloted to be more and more autonomous. As the technology becomes more advanced it becomes easier for people to use. To fly a Predator, you used to need to be a pilot,” he said.

“The field of autonomy is going to continue to advance regardless of what happens in the military side.”

This post originally appeared at Defense One. More from our sister site:

As debate goes on, the military prepares for climate change