There’s a phrase in Assamese to describe families like ours: bhal ghor. Literally, it means “good home.” It’s thrown around a lot during matrimonial matchmaking. Or when a child applies to nursery and his mum needs to impress an admissions officer. Or if you need to send money to your village and only a stranger can do the hand-off: “He’s from a good home. Don’t worry.”

Intentionally vague, the catch-all sentiment sums up a family’s ethics and economics and helps create instant trust among certain types of people. The idea makes it possible for class to be defined by collective output rather than one’s own job and income—an important distinction that explains why India’s middle class numbers as small as 50 million, according to some, and as big as 250 million, according to others.

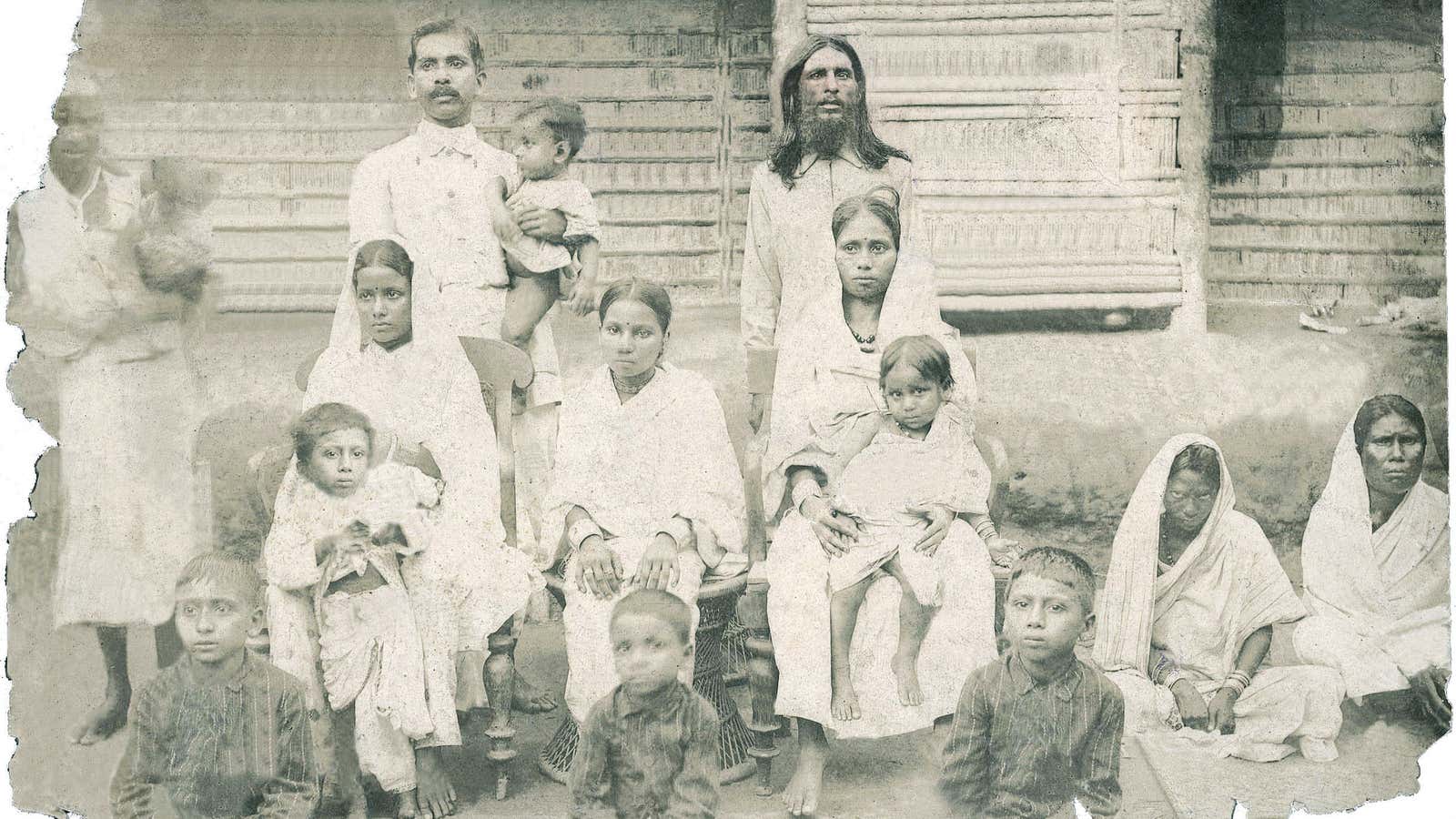

And so my huge extended Indian family—10 siblings on my mother’s side, eight on my father’s—spans college dropouts and MBAs, refinery managers and doctors, auto mechanics and contractors. Until the last of the lot left our village on the banks of the Brahmaputra in 1991, aptly the year India opened up its economy, many relatives on my dad’s side still toiled in agriculture—like two-thirds of the country back then, and about half now. I also have an uncle who is a tea seller, just as Narendra Modi once was.

To understand how Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party cruised to power this week, it’s worth looking back on the dynamism of the Indian family. It has been the bedrock in a society riddled with poverty, corruption, crummy infrastructure, mass unemployment. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Indeed, for as long as I’ve been going back to my parents’ native state of Assam, beginning with my first trip as a toddler in 1978, much of my own brethren felt stuck in time, trying to find the bridge between the India that was and the one of call centers, GDP growth, five-star hotels. But they were from a good home. There was at least that.

It is no coincidence that the amorphous political platform of the incumbent Congress Party is referred to as mai-baap. Mother-father. Like doting parents, the party of India’s independence pledged to take care of you, an attitude rooted in a once-socialist economy that perpetuated even amid a recent embrace of western-style capitalism. The problem with this patronage is that it is easy to mask shortcomings under Mai and Baap. About a decade ago, a cousin of mine paid a bribe to secure a government job, only to have his fixer never deliver. I asked him to send me his c.v. so I could help; it was four lines long. I called and scolded him. “Sorry,” he said. “I thought you were going to just get me the job and this was a formality.”

For much of India’s 67-year history, the majority of my family has supported Congress. And not just as voters—my mother’s great uncle was a member of the legislative assembly, and her father and uncles wore the signature homespun khadi of the party until their deaths. During Assam’s separatist movement in the 1980s, some aunts and uncles grew more politically active and idealistic and supported local (and Communist) parties—but that fizzled out as a generation matured and a movement immatured. Like the rebel teen who eventually moves back home, back to Congress they went. In recent years, a handful of cousins, upset over the number of Bangladeshi immigrants in Assam, threatened to defect to the Hindu fundamentalist BJP. Some did. Yet most kept faith that the government under chief minister Tarun Gogoi, a Congress Party stalwart, would get something done. “Poisa khai kintu kaam koreh,” was oft-repeated to justify corruption in his cabinet. He eats money but he works for it.

When I lived in India between 2006 and 2008, my trips to Assam grew more frequent, for weddings and funerals, reporting assignments and renovations on my parents’ home in Guwahati. I kept waiting for another revolution. It never came.

Then last month, amid the biggest election in human history, I landed in an India that somehow and suddenly felt different. The revolution was not as I’d expected—no mass protest in the streets over inequality and women’s rights, graft and malnutrition, wages and labor conditions. Yet there was a palpable shift in a nation’s psyche, most evident in my own family. Dozens of relatives were firmly in Modi’s camp.

“Our family was with Mahatma Gandhi’s original Congress,” my mom’s cousin told me. “The present-day Congress is a fragment of the original Congress. We’ve lost our hope.”

What changed?

Corruption is still rampant in Assam. Some infrastructure, such as roads and airports, are better. Power and water supplies remain unreliable. But these are perpetual problems; my family had looked the other way many times.

Then I pondered the sudden absence of that phrase: the good home. It didn’t come up as it used to, which is to say all the time. Like when I asked about the family, the “home,” of a woman just married to my cousin. “Works at Indian Oil. Plays badminton.”

“Her father?”

“No,” laughed my cousin. “The bride.”

A newfound individualism was asserted, too, by rattling off possessions: cars, phones, flats. But it also manifested through that most precious commodity: time. My trip coincided with another cousin’s wedding. In the past, everybody in the extended family showed up to everything. No longer: attendance at rituals were squeezed in between jobs and school drop-offs, tutoring sessions and dentist appointments. The bride’s side of the family asked for one ceremony to be moved up, so everyone wouldn’t have to take off of work.

This might sound like oversimplification, especially for denizens of India’s major metros where the extended family disbanded and the pace of life quickened long ago. Yet it is places like Assam that form the heart of India; it is only here that a real Indian revolution can begin. And if the old adage about democracy is true—that people get the governments they deserve—it is the people who must change before their government. And so in Assam, the question is not what changed but who.

I type these words knowing the next prime minister of India throws so much of the country’s founding values, namely secularism, into doubt and disarray. He is easy to dismiss as a despot who oversaw a bloody, unforgivable period of India’s history, specifically the Gujarat riots of 2002. Yet for the sake of India’s future, it is necessary to understand his appeal and what his rise means at this critical moment for families like mine. His opponents are perfectly right to worry—but they are wrong to prop up the old ways of Congress as an option the country could continue to tolerate. They are wrong not to delve into the despair and demographics that fueled Modi’s victory.

The loss of an old way of life, coupled with the rise of individualism and a survival instinct in places like Assam, proved fruitful for Narendra Modi. The middle class woke up from its indifferent slumber and decided to take matters into its own hands. With an 80% voter turnout rate, Assam’s was among the highest in the country. The BJP, once a non-existent force in the state, gained at least seven seats, thanks to the world’s newest “me me” generation. Trends on Facebook India during elections were especially telling, their order even more so: jobs, education, corruption.

Charisma—that’s what supporters say is behind the so-called Modi wave. During my stay in the region, it looked more like a well-oiled marketing machine: an Assamese jingle devoted to Modi played on the radio, he wore signature Assamese garb in countless billboards, makeshift rallies were held along major highways and narrow footpaths deep inside villages.

Mainly, I think Modi benefited from a people’s fatigue, a desire to believe in him, and his being in the right place at the right time. The history of families like mine have been tangled in the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty for India’s entire existence. Yet economic instability and uneven prosperity are forcing a realization that the country must find a path toward growth that is truly sustainable—not rooted in the riches of an elder brother, the inheritance of ancestral land, the occasional freebies from Mai and Baap. Suddenly, the middle class has a desire to be a part of the political system, help create a vision for its economic future, not simply take crumbs or cover from the more prosperous. If there is a silver lining of Modi’s ascension, this engagement, this redefinition, this seizure is it. From the shadows of good homes across India, the revolution has come.