All the ingredients are there for a proper arms deal: A former government official with connections to the military-industrial complex. A stockpile of Soviet arms in Ukraine. Soldiers in Syria with a yen for ammo and cash to burn. The biggest problem? Getting the arms from eastern Europe to the battleground without alerting international authorities or tipping off your enemies.

The story isn’t about Russia or the United States. It’s about Russia and the United States.

This week, the Wall Street Journal shone a light (paywall) on one American’s thwarted effort to run guns into Syria for the anti-regime Free Syrian Army. Last fall, analysts at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS) in Washington assembled public data to identify a network of businesses (pdf) in Ukraine and Russia at the heart of Russia’s efforts to arm the Syrian regime. The two stories have a lot in common, with a key difference being that Russia’s government is a lot more invested in arming its side of the conflict.

The guns of Odessa

While weapons of all kinds have cropped up throughout the Syrian conflict, from the chemical weapons that made president Bashar Al-Assad an international pariah to homemade rockets, the rebels have two main problems: Getting enough rifles and ammunition to give them a basic infantry force, and—the bigger problem—countering the regime’s vast military advantage, especially as it has aircraft and the rebels don’t.

Many weapons in the conflict hail from the former eastern bloc, according to surveys of small arms in Syria (pdf) that are admittedly unscientific. There’s a reason for this: The Soviet Union cranked up a massive arms machine, and when it collapsed, the combination of chaos, weapons stockpiles and criminal entrepreneurship gave men like Viktor Bout and Leonard Minin careers as arms dealers.

When it comes to recent arms deals to Syria, though, the C4ADS analysis sees a a new evolution in arms transit.

Using software developed by Palantir, the secretive Silicon Valley big-data firm, C4ADS tracked an interconnected network of businesses, often hidden behind shell companies, who handle most Russian arms shipments. The “Odessa network” it describes is centered on politically-connected Russian and Ukrainian businessmen and the Ukrainian seaport of Oktyabrsk, a former Soviet military base. At least 10 ships in the network visited Syria in 2012, while dozens of Syrian vessels have traveled back and forth to Oktyabrsk, according to C4ADS.

The most prominent firm discussed is the Kaalbye shipping group. It was founded by Igor Urbansky, a former Soviet naval captain who was a Ukrainian government deputy minister from 2006 to 2009, and Boris Kogan, whose business connections tie him to Russia’s defense industry. Kaalbye-operated vessels have shipped all kinds of cargo, but they have also have an important business transporting weapons to conflict zones on Russia’s behalf.

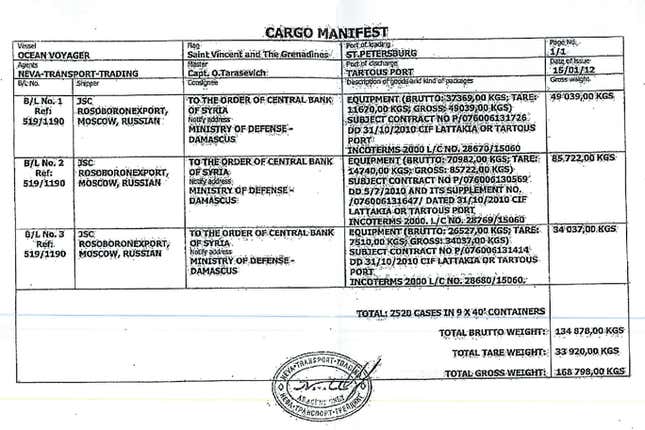

At least one of Kaalbye’s ships, the Ocean Voyager, took a shipment from Russia’s arms export agency to Syria’s ministry of defense in 2012, according to a cargo manifest obtained by C4ADS. The manifest (below) lists the contents of the shipment as only “equipment.” Kaalbye’s representatives at the law firm Patton Boggs declined to comment to Quartz, but the company has acknowledged this delivery to Syria and says it is the only one that occurred that year.

The C4ADS report also notes that other Kaalbye vessels dropped out of sight of global ship-tracking databases at the same time that Russia increased weapons deliveries to Syrian ports in 2012 and 2013. While it’s possible that this is a coincidence, and the innocuous product of less-than-perfect infrastructure, C4ADS suggests the timeline could point to Kaalbye ships shutting off transceivers while making weapons deliveries.

It’s likely not illegal for Russian ships to deliver such cargos, depending on the jurisdictions they pass through en route. But delivering weapons to Syria would violate Western sanctions. Kaalbye, presumably concerned that other lines of business—including potential US government contracts—might be affected by the C4ADS allegations, threatened to sue the think tank for defamation and hired a public relations firm to challenge its findings. Kaalbye also provided evidence to the Washington Post that one of the missing ships was in fact using its tracking system and did not stop in Syria.

But in April, the think tank preemptively sued the shipping firm for interfering in its business. The back and forth between the company’s American representatives and C4ADS is a saga in itself, and more may be revealed in early June, when Kaalbye must respond to the suit in court.

Kaalbye’s role aside, Western intelligence agencies are confident that Russian (and, to a lesser extent, Iranian) supplies—from helicopters to tanks to ammunition and diesel—have allowed the Assad regime to wage war despite not having much of an industrial base or support from other nations.

This analysis of Russia’s arms shipment logistics also, incidentally, helps explain president Vladimir Putin’s interest in influencing or annexing eastern Ukraine. Yes, it’s a former part of the Soviet empire where a lot of ethnic Russians live; but it’s also vital infrastructure for Russia’s efforts to project power abroad today—and a profit center for the Russian defense industry.

And that’s why it’s interesting that a stockpile of weapons a group of Americans sought to provide to Syrian rebels also hails from Ukraine.

There’s something about Schmitz

About a year ago, according to the Journal’s story, a former US defense department official named Joseph Schmitz approached the leader of the rebel Free Syrian Army. He offered to give them 70,000 assault rifles from Ukraine and 21 million rounds of ammunition, for which an unnamed Saudi prince would foot the bill. Given that the fighting force of the Syrian rebels is estimated at perhaps 100,000 strong, it would have been a substantial injection of firepower—though it would not solve the air superiority problem. At the time, the US government was dithering over whether to provide much in the way of weapons at all, given the risks that they might reach anti-American groups or fail to change the dynamics of the conflict.

Schmitz, who had worked as the independent auditor for the US Defense Department, left that job in 2005 after coming under Congressional criticism for close relationships to contractors he supervised; no wrong-doing was ever identified. He became the the general counsel for Blackwater, the notorious US mercenary firm, before going into private practice as an attorney. Last year, the Journal reports, he somehow arose as the middleman between the unnamed Saudi benefactor, two unnamed US weapons brokers, and whoever owned those weapons and the capacity to transport them to Syria.

This all came to a halt, according to the Journal, when a US spy in Jordan apparently told one of Schmitz’s partners that the US government didn’t want any freelance arms dealing in Syria. This was before Schmitz had applied to the State Department for an official license to broker such weapons sales overseas, which he said he intended to do all along, though both arms trafficking experts and members of the Syrian opposition were skeptical of his approach. Soon, evidence that Syria had used chemical weapons against civilians in rebel-held areas loosened US restrictions. Now, the US is directly supplying training and an unknown amount of small arms and anti-tank weapons to select Syrian rebels across the border from Jordan—but still no anti-aircraft missiles.

How much do weapons cost?

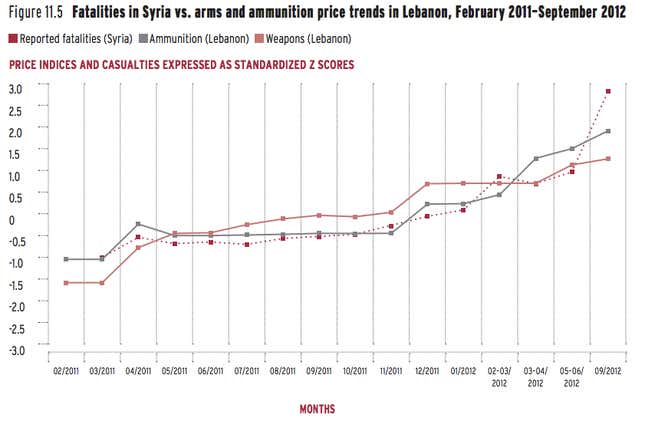

The more the war in Syria drags on, the higher the demand for weapons. Here’s a chart from the Small Arms Survey (pdf) looking at the correlation between increases in casualties and the cost of weapons:

In 2012, rebels seeking armaments in Turkey found that just one cartridge for a machine gun or assault rifle cost $2-$4, while a common assault rifle cost upward of $2,000. That puts some perspective on the value of Schmitz’s offer; at those prices, that much weaponry would have cost the rebels perhaps a quarter of a billion dollars. Presumably, the wholesale cost to Schmitz’s group would have run cheaper.

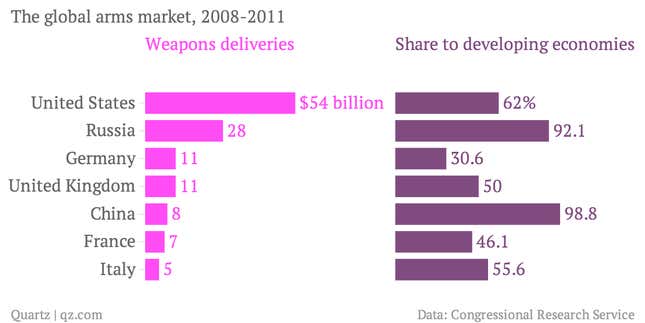

But those numbers also underscore that the conflict can be a boon for defense contractors. Russia exported some $17.6 billion in weapons in 2012 alone, and that’s just the arms transfers it reports; even if the government is underwriting most of those costs, it’s still promoting its industrial base. When it comes to arms sales, the US is it’s only rival, exporting perhaps $60 billion worth of military goods in 2012, although that’s an unusually high number driven by advance sales. Here’s a more representative picture of the global arms market:

What’s most worrisome is that these data are mostly focused on large armaments—planes, tanks, ships and bombs—and not small arms. While the dangers of mechanized inter-state warfare are well known, small-arms trafficking is harder to spot, and that has people worried, since it increasingly fuels destabilizing conflicts from Africa to Latin America. Last year, the UN passed a treaty in part designed to create more transparency around arms trading and urge countries not to send weapons knowingly to places where they’re likely to be used in genocide, terrorism, and the like. The US has signed the treaty; Russia has not.

As the world’s top arms dealers square off in Syria, the situation looks to be approaching a stalemate. Fractured rebel groups retreating in the face of pressure from a regime confident in its ability to consolidate power and wait its enemies out. That’s not likely to change unless the US or someone else decides to send anti-aircraft weapons to the rebels. But as long as the steady migration of weaponry from eastern Europe to the Middle East continues, the suffering isn’t liable to stop anytime soon—the latest count by activists attempting to track the disaster is is that more than 160,000 people have been killed, and many more have been turned into refugees, with the UN claiming that Lebanon alone will hold 1.5 million by the end of the year.