Sears reported earnings today, and it wasn’t pretty. The US-based retailer posted a loss of $402 million. This particular loss was driven by a poorly performing electronic-goods division—which the company hopes to turn around by focusing on “empowering connected living,” whatever that means—but it’s another chapter in an ongoing decline.

The company’s been shedding assets recently. CEO Eddie Lampert spun off the Lands’ End clothing brand earlier this year, and the company’s small-format stores, Hometown and Outlet, last year. Sears announced plans to close 80 more stores in 2014 after shuttering more than 90 last year. And Sears Holding is now looking at “strategic alternatives” for its auto centers, and to sell off 51% of its stake in Sears Canada.

Selling or spinning off assets has returned money to shareholders (Lampert’s hedge fund is by far the largest) and provided cash to keep the company running as it tries to transform—most recently to a member-centric discount model. But none of Lampert’s many changes have boosted sales or even stopped the bleeding. And the dwindling cash pile hasn’t gone to stores, in which the company has underinvested badly. Spinning off Lands’ End, one of the company’s most lucrative divisions (paywall), has meant higher losses for the rest of Sears. One analyst told Bloomberg that “it would take almost an act of God at this point for them to turn this around.”

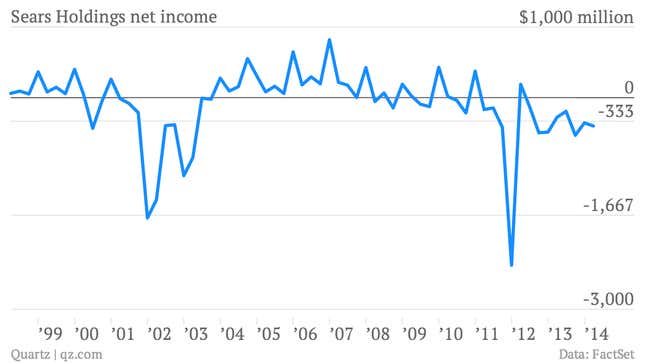

Taking a underperforming company and spinning off assets to try and unlock value is nothing new. But Sears is losing so much money that investors are starting to balk. The company has been hemorrhaging money for some time, and this is the eighth consecutive quarter that it’s lost more than $100 million:

Lampert, who made his fortune in hedge funds, combined and took control of Sears and K-Mart in 2005. There were a few tough but decent years. Then the wheels started to come off. Besides that fact that just about every one of its retail operations faces growing competition from e-commerce, Sears has also been hurt by Lampert’s idiosyncratic management and organization philosophy, detailed last year by Bloomberg Businessweek.

Inspired by the libertarian philosopher-novelist Ayn Rand, Lampert split the company into 30 autonomous divisions that competed with each other for resources. The theory was that selfishly competing managers would run their divisions more efficiently, boost performance, and provide better data about what was working. The result has been infighting and dysfunction.

Lampert repeatedly emphasized in his pre-recorded earnings presentation that the company’s spinoffs and sales are in support of its strategic transformation. But by the time it’s done “transforming,” there might not be much left that customers want.