Every year in spring, seals birth baby seals on the sea ice that lines Newfoundland’s coast. And for the last few hundred of those years, hunters have descended shortly thereafter, bludgeoning and shooting many thousands of young seals to death, collecting them for their downy pelts.

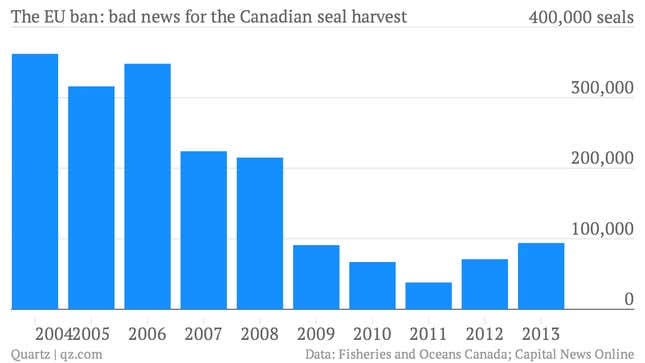

This spectacle of brutality prompted the European Union to ban the import and sale (paywall) of any products made from seal in 2009. Canada retaliated, bringing the dispute to the World Trade Organization to accuse the EU of violating free trade.

It turns out the WTO agrees that the EU is breaking its free trade obligations—but thinks that’s okay. Addressing the EU’s “public moral concerns on seal welfare” is more important, the WTO’s appellate body said in a final ruling today.

It’s a landmark decision; this is the first time the WTO has accepted animal welfare as grounds for violating basic trade agreements. This opens the door for countries to invoke animal welfare concerns as a basis for trade bans.

Some find this distressing. “Upholding the seal ban on moral grounds sets a dangerous precedent that could lead to trade bans affecting other sustainable-use industries,” Aaju Peter, an Inuit lawyer and sealskin designer, said in a recent press release about the dispute.

In this case, “sustainable-use” likely refers to the commercial killing of animals in a way that makes sure to use as many of their body parts as possible. (The EU ban includes exceptions for seal products from hunts conducted by Inuit communities that do so. However, it discriminates in favor of Greenland’s Inuit-hunted seal products, ruled the WTO, directing the EU to fix that.)

But the WTO’s ruling didn’t support a ban on killing altogether; rather, it found it plausible that the whole clubbing thing was “inhumane” enough to offend European ethics, and that protecting community morals was more important than enforcing trade obligations. The problem is that it’s often hard to kill animals on an economic scale without lapsing a little on the humane part.

It’s not that animal welfare hasn’t come up before at the WTO. But in the past, countries have framed their cases in trade terms. For instance, in an effort to prevent the mass slaughter of dolphins caught in tuna-fishing nets, in 1990 the US instituted rules designed to protect dolphins, allowing companies in compliance to label their tuna “dolphin-safe.” A few years ago, Mexico brought the US to the WTO, arguing that the labeling law discriminated unnecessarily against Mexican tuna; the WTO agreed. (The US has since changed its dolphin-safe tuna labeling rules to up its own compliance, not just Mexico’s; Mexico is bringing another challenge to the WTO.)

Would the US now be able to protect the blocking of Mexican tuna on the basis of public moral outrage stemming from love of Flipper? Maybe. But the even bigger deal here goes beyond animal rights alone. Thursday’s ruling was the first time the WTO considered whether a member could restrict trade on the basis of a moral rationale as opposed to a policy objective. That’s pretty fundamental.