I graduated from the University of California Santa Barbara in 2003. The four years I spent in Isla Vista—the square mile that abuts UCSB and the Pacific Ocean—were some of my happiest. I lived with five girlfriends, half a block from the beach. On Sunday mornings, we would drag an old comforter onto the front yard, curl up in the sun, and recount the escapades of the night before. That house, on a street named El Nido, which is Spanish for “the nest,” sits just yards from where Elliot Rodger opened fire on students on May 23, in a violent rampage that killed students Katie Cooper, Veronika Weiss, George Chen, Cheng Yuan Hong, Chris Michaels-Martinez, and Weihan Wang, and traumatized countless others.

Until Rodger attacked its residents, I had no idea that my beloved, beachfront college community, which has rightfully earned its Spring Breakers reputation, was also the unlikely source of my feminism. I was no gender studies major or women’s rights activist, but it was at UCSB that I connected with the girls who remain not only my closest friends, but increasingly, as we negotiate careers, relationships, and kids—my female role models. As a journalist in my thirties, I’m privy to constant conversations about how to “balance” (or not) a successful career and a happy family, Lean In, be #bossy, and get swimsuit-ready by beach season. In terms of utility, none of this approaches the love, advice, and support I get from text messages, phone calls, and too-rare get-togethers with the girlfriends I made in Isla Vista.

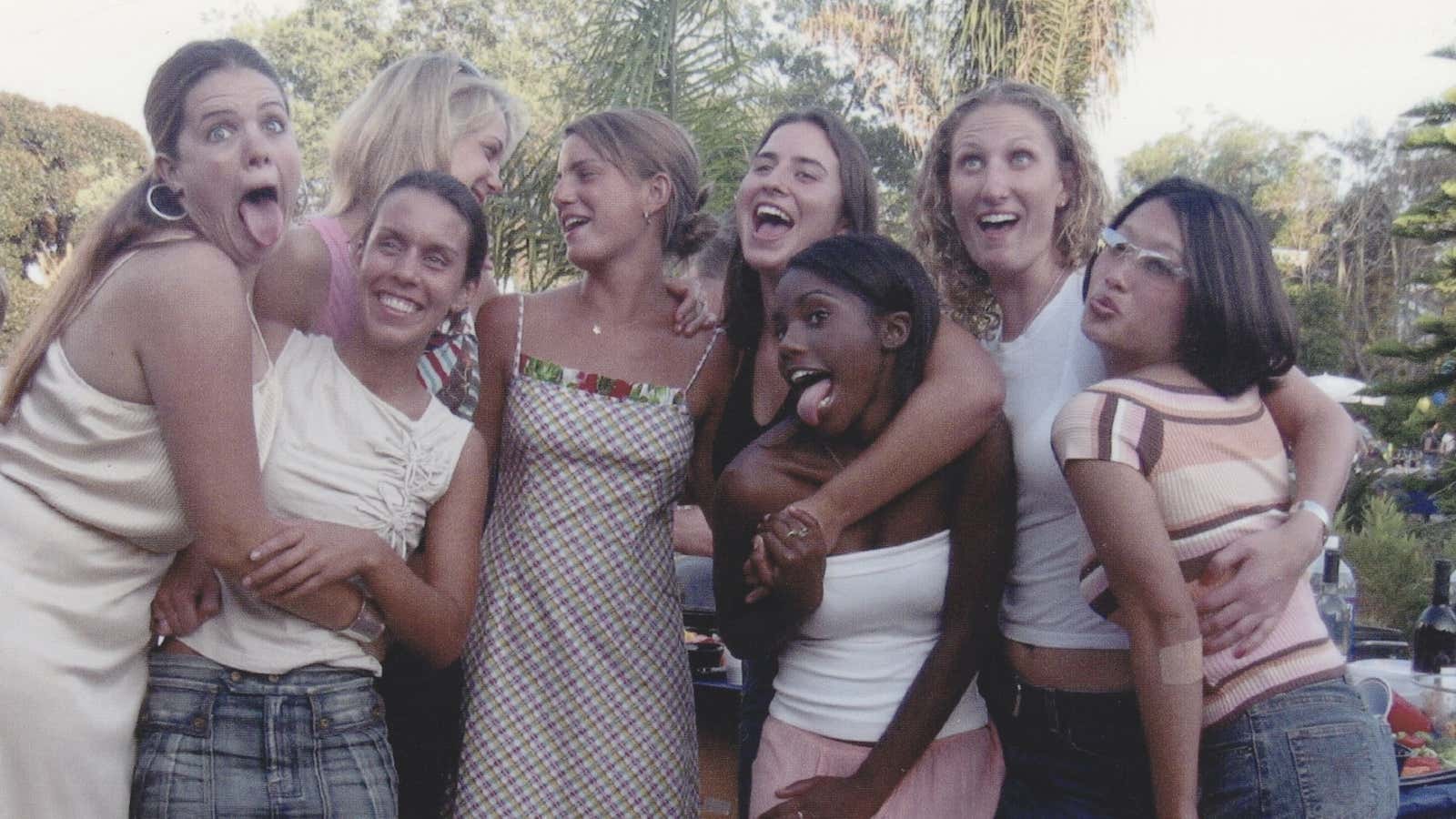

Elliot Rodger plotted and explained his attack in a 137-page manifesto and a video he uploaded to YouTube. He blamed women—and rather specifically, the young women of Isla Vista—for his massacre, or, as he called it, retribution. From Rodger’s rants, I understood that a decade ago, we too would have been the subjects of his vitriol, as so many of his neighbors were. “The whole area was full of young people enjoying their pleasurable little lives,” he wrote dismissively, as he planned vengeance on the affectionate couples and short-shorted girls he blamed for his alienation and virginity. (“If I can’t get laid there, then there is no hope for me,” wrote Rodger—a commonly held belief about Isla Vista that would get a laugh from my fellow Gauchos given another context.) As most of us know, he was far from the first college student to endure virginity or loneliness. And many have pointed out his place in an alarming movement of misogynist extremism. His actions galvanized a backlash against this hateful, violent, and entitled ideology, as the amazing proliferation of the #yesallwomen hashtag on Twitter proves. Scrolling through those tweets, I was grateful for the conversation about the everyday misogyny that yes, all women endure. And it occurred to me that my own greatest weapon in whatever private war misogynists are waging is the strength I draw from the girls I met in Isla Vista. Today our group of eight includes successful recruiters, directors, activists, artists, writers, editors, mothers, and wives. But we used to just be a bunch of bikini-clad girls on a patchy lawn with a beer pong table.

I was never one of those high-schoolers with a gaggle of girlfriends. I hung out with the guys, and when they told me I was one of them, I took it as a compliment. When I got to UCSB—a transplant from St. Louis, Missouri—it took me the better part of a year to find my friends. At a school of 18,000 undergraduates, it’s a bit of a miracle I found them at all. The towering off-campus freshman dorm where I lived held nearly 1,400 students and sat just shy of a mile from the Pacific Ocean—as far from the beach as one can get in Isla Vista. The dorm was a weird place, where students shuffled around in pajama pants and slippers, as if languishing indoors despite the glorious setting was the best way to exercise our new, parent-less freedom. Even for the happy and seemingly well-adjusted, the transition from home to college can be tough. Elliot Rodger wrote about the oppressive loneliness he felt in Isla Vista, while the rest of the world partied on in apparently carefree promiscuity around him. His profound belief that his loneliness was unique was not just narcissistic, it was tragically absurd.

At some point during the latter half of my freshman year, maybe a bit bored and lonely myself, I got into the habit of riding my bike to Sands, one of Isla Vista’s main beaches, for the sunset. The town’s westernmost beach, Sands sits at the end of series of dirt paths that meander along a bluff overlooking the ocean. Those paths hold the warmth of the sun all evening, and the air smells like a mixture of sage, sea, and tar. An oil rig sparkles on the horizon, and there’s a giant, twisted, fallen tree that’s perfect for sitting on. It is pure Isla Vista.

I can’t remember if I invited Deanna—a fellow freshman I met in the dorm’s elevator after overhearing her talk about a Ben Harper concert—on one of those rides. Maybe we just bumped into each other at the bike racks, but at some point we started pedaling out to watch the sunsets together. Later that spring, she invited her girlfriends along. They all lived on the tenth floor—the all-girls floor—and were a gaggle if ever there was one. They didn’t all have bikes, but someone had a station wagon, so we piled in. There was Erin, a soft-spoken soccer player from Washington state, Chrystine, who made sure the hip-hop in the car was on blast, Marjorie, a lanky-limbed New Englander always quick with a joke, and Alice and Cristina, a pint-sized pair of friends with matching mega-watt smiles. We were white, black, Filipina, tall, tiny, and all over the map when it came to our interests. All we had in common that night was that we had gone to Sands to watch the sunset. Some of us lingered longer than others, huddled into our new UCSB hoodies in the fading light, while the ones who got chilly trickled back to the car.

Riding back to the dorm that night in the station wagon, it occurred to me that I had finally found my girlfriends.

The fall of my freshman year, my parents finalized their divorce and sold the house I grew up in, so the safety and belonging I found with the girls in that station wagon, and later, in our house on El Nido, was welcome. I held tightly to them. For four years we stuck together, in spite of widely varied interests and disparate social circles—the tiny core intersection of a flowering Venn diagram. In that intersection were Sunday night dinners with cheap wine and store-bought spinach dip, outdoor study sessions, a spate of ridiculous theme parties (any excuse for an ultra-suede jumpsuit), mildly contained boy craziness, and a penchant for brownies eaten straight from the pan.

Also in that intersection, I know now, were professional ambition, aggressive individualism, wide open-mindedness, screwball humor, cultural curiosity, and generous love and respect—especially when it came to family, which, by extension, came to include one another. Studies have shown that women with strong female friendships lead longer, happier, healthier lives, and that we often form those friendships before we hit the age of 25. So while a bevy of beach babes or sorority sisters may seem superficial, the relationships they’re forming will help them handle a world that can be, at best, unfair, and at worst, fatally violent toward women.

As I watched the details of the shooting in Isla Vista emerge all weekend from my home in New York, I ached for the companionship of my girlfriends. In the days following the attack, my former professor, global terrorism expert Mark Juergensmeyer, wrote about Rodger’s actions as an act of terror, linking them (as many have) to a western culture of violence. In Juergensmeyer’s classes, we learned that terrorists methodically strike their subjects’ symbolic centers—those places that will shake their victims to their cores. I can say with certainty that Elliot Rodger did this to me. A random, insane shooting in Isla Vista, which this at first appeared to be, was alarming. The disorientating devastation I felt upon discovering this was a calculated misogynistic attack was something else entirely. Isla Vista, known for its raging parties, may never have been a particularly innocent place, but for a bunch of girls—and guys—on the verge of growing up, it was a sanctuary.

In the decade since we’ve graduated, we Isla Vista girls have spread across separate cities, coasts, and for a while, countries. At first it was weddings that brought us together. More recently, we’ve had to reserve random calendar dates as similarly sacred, just for the sake of togetherness. Two weeks ago, we gathered in a rented house just south of Santa Barbara for a belated 10-year reunion. With husbands, boyfriends, kids (eight little boys, incidentally), and one dog, we cooked, walked, talked, drank, swam, and laughed. Saturday afternoon, we dragged our growing families on a pilgrimage to Isla Vista. We took a picture on the front yard at El Nido and brought the kids down to the beach, where students were surfing, tossing Frisbees, and laying in the sun. It was perfect.

The following weekend, before I went to bed, I sent a group text: Such a quiet Friday after last weekend. I miss my girls. That night as I fell asleep, a barrage of affectionate replies came through. And then, in the morning, the news of the shooting. Chrystine immediately warned us not to watch Elliot Rodger’s YouTube video, which so many media outlets had posted with their coverage. She hoped to shelter us from his deeply disturbing diatribe—even more frightening for its familiar setting. There’s no inoculation against the virulent hatred that his attack revealed. But in her way, Chrystine—and all my girls—had already protected me.

I just hope that right now, the girls in Isla Vista are holding one another equally close. I had never recognized the sustaining bonds, fierce support, and unconditional love of one another we formed there as anything other than friendship. Now I realize, it’s also feminism.