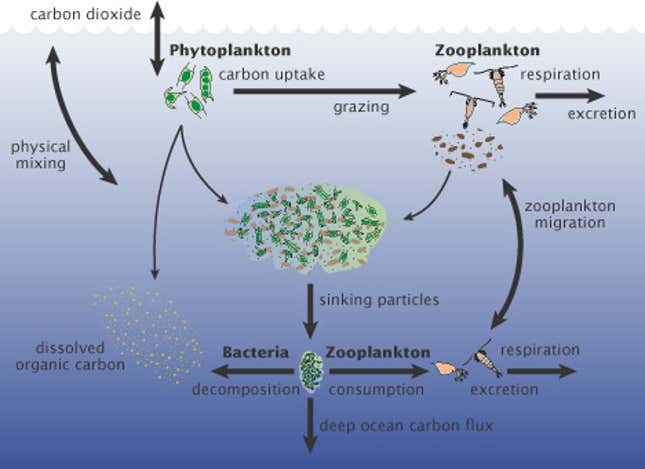

Humans are pumping roughly 33 billion tonnes (36 billion tons) of carbon dioxide into the air each year. If all that showed up in the atmosphere, it would accelerate global warming even further. The ocean, however, absorbs around half of that CO2. Phytoplankton (essentially, microscopic plants) that live near the sea’s surface take in a lot of it as they photosynthesize, ultimately flushing the CO2 into the cold, dense depths, where it stays trapped for centuries.

How does it travel all those fathoms? Until now, scientists have chalked it up mainly to gravity—to the sinking of phytoplankton that have either died or been eaten and excreted by fish. But new research reveals that we have deep-sea fish to thank for transferring a lot of that carbon into the depths—and that sinking alone wouldn’t do the trick.

In fact, bottom-dwellers transfer more than a million tonnes of CO2 a year from surface waters of the UK and Ireland, helpfully storing between €8 million and €14 million ($10.9 million and $19 million) a year in carbon credit value, says a new study (paywall) by a University of Southampton team. Killing too many of those fishes, as well as the ones they feed on, risks damaging the ocean’s ability to store carbon, leaving more CO2 in the atmosphere.

From top to bottom

Though the cycle is complicated, there are two main fish groups in this story: those living in the sea’s middle swath, around 200-1,000 meters (650-3,300 feet) down; and the deep-sea set best known for fangs, underbites and Gollum-like looks.

Every night, billions of middle-layer fish head up to the giant plankton salad bar on the surface to chow down on plankton, small plankton-eating organisms, upper-level fish, and each other, swimming back down once they’re done. Scientists recently discovered (pdf) that these mid-level fish are likely just as critical as upper-dwelling species to the “biological pump,” as they call the mechanism that moves carbon deep into the sea. Presumably that’s because, like the plankton, these mid-level fish sink when they die, taking their CO2 load with them—but they’re much more efficient at moving that carbon down than if it had to sink all the way from the surface.

As for deep-dwelling fish, though, everyone’s assumed they live mainly off nutrient crumbs falling from above. Since they’re more than a kilometer below the ocean’s surface, it’s hard to tell.

According to the new study, however, that’s not the case. A majority of deep-sea fish are cruising up to the middle layer during the day and tucking into the fish that live there, say the researchers. In fact, the deeper-dwelling the species, the more it tends to get its food from other fish.

The fact that these deep-sea critters are eating middle-level fish at far higher volumes than anyone previously realized explains how a lot of that mysteriously descending carbon gets so deep. If the researchers are right, this food web also means gravity alone isn’t nearly as critical to marine carbon storage as we’ve long assumed.

Which means, then, that overfishing threatens this biological pump, because it puts both layers of fish at risk. Though fishing vessels tend to target middle-level species, they also go for some deep-sea fish like blue ling, red seabream or black scabbard fish. And unwanted fish of both levels are also accidentally caught in huge volumes as “bycatch.”