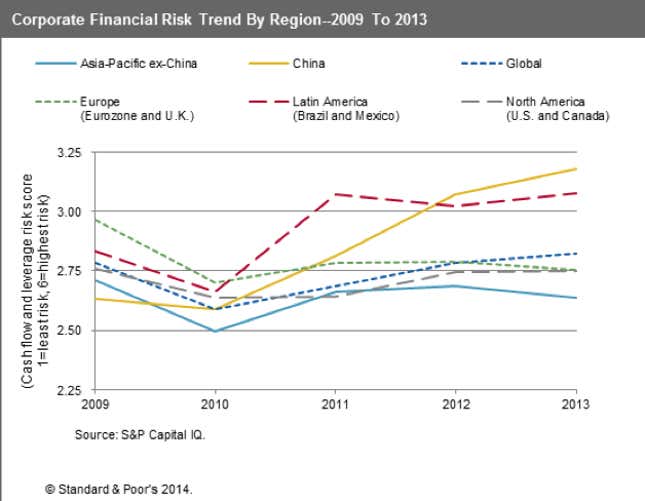

Back in 2009, China’s 8,500 listed companies were in much better shape than their global peers. No longer. The average Chinese company now has worse cash flows and more debt than other similar firms elsewhere in the world, says Standard & Poor’s, a ratings agency.

So great has China’s borrowing binge been that its companies racked up $14.2 trillion in debt at the end of 2013, blowing past the US’s $13.1 trillion to become the world’s biggest corporate borrower. This, says S&P, is worrying since a “higher risk for China’s borrowers means higher risk for the world.”

How did China ascend to the top of the corporate debt list a year before S&P expected it to?

The story takes us back to the global financial crisis. After Lehman Brothers collapsed in late 2008, China’s leaders opened the lending taps, pumping huge sums of credit into the system via state-owned banks. Much of that went into growth-juicing sectors like real estate, shipbuilding, and steelmaking. The timing was bad; China’s economic growth had already peaked in 2007, and was starting to slow.

As Chinese companies expanded their ability to produce—building new factories, buying more land, and the like—they created a excess of supply that began to drive down prices. Then the slowing economy hurt cash flows even more.

But instead of letting companies default, leaders kept pumping more money into the system, in part through official channels, though also by allowing China’s off-balance-sheet credit system—better known as “shadow banking“—to flourish. That shifted money to companies with terrible credit records and weak cash flows that no sane banker would lend to. Now, as much as one-third of corporate debt—between $4 trillion and $5 trillion—comes from the shadow banking sector. An enormous amount of this funding was used not to invest in new businesses, but to pay off old debts.

Though these problems became too big to ignore last year, they keep getting worse. That could hurt the global economy, says S&P. “As the world’s second largest national economy, any significant reverse for China’s corporate sector could quickly spread to other countries,” it notes in a report.

Unfortunately, Chinese corporate borrowing isn’t really slowing down. S&P says that, by 2018, Middle Kingdom companies will have issued between $21.9 trillion and $23.9 trillion in debt—equal to one-third of global corporate debt, including refinancing and new issues. That implies an average annual increase of between 7.5% and 9%—much faster than China’s economy is able to grow.