As we report this week, in much of the developing world, mobile money is evolving. Initially just a means of making payments, it’s now becoming a platform for an entire financial-services industry. But one of the world’s biggest and poorest countries has remained immune to the attractions of mobile money. Despite the potential benefits, “the uptake has been limited,” says Graham Wright of MicroSave, a financial-inclusion organisation working in India. “And because of those challenges, the mobile operators are unsure about how much to invest in this business.”

That doesn’t mean there isn’t opportunity. India has 15 mobile money providers, second only to Nigeria. Of the 904 million mobile subscriptions in India, 371 million (pdf) are in rural areas. Analysts think that mobile money transfers in India could be worth $350 billion annually (paywall) by next year. Yet the state of the industry remains small: Less money moves through wireless transfers in India than in either Pakistan or Bangladesh, both of which have smaller, poorer populations.

So why, despite boasting 15 mobile money services, does India lag so far behind other developing nations?

The simple answer is regulation. India requires mobile operators to work with banks to provide the services. Mobile networks would like instead to have their own agents who can cash out the digital money into hard currency. Much of the infrastructure is already in place, because there are so many locations where customers can top up on airtime. But the mobile operators aren’t allowed to use those sales outlets as financial agents.

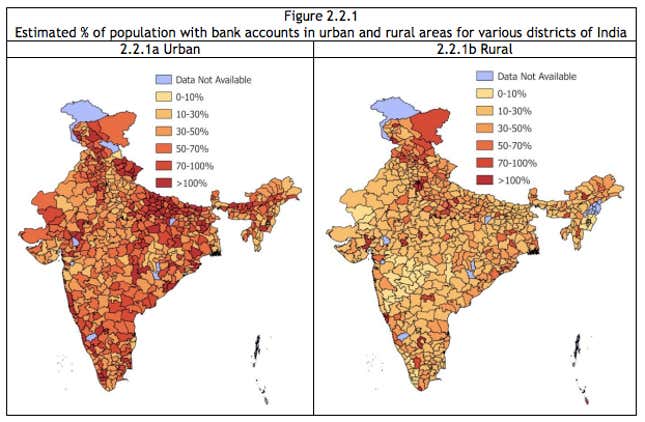

Yet the banks aren’t filling the gap. They have failed to serve rural areas, especially thinly-populated ones. Nor are they particularly keen on sending agents to operate in small villages. A report (pdf, p.31) on financial services for the poor, commissioned by the Reserve Bank of India, called the situation in both rural and urban India “grim,” with 64% of Indians lacking bank accounts. ”The business case for providing mobile money services to the unbanked in the most remote rural areas of India is not appealing to banks,” reports the GSM Association (pdf), a trade body of mobile operators.

“If you look at all the unsuccessful mobile money deployments that haven’t taken off around the world, it is almost always because mobile operators and banks half-went into it and didn’t spend enough to reach the scale they need,” says Wright.

Rural customers are too much hard work for big financial corporations, particularly when there’s a large urban population that’s more affluent and easier to reach. Mobile operators, on the other hand, don’t offer lucrative loans or fancy financial services; the profits in mobile money come from large volumes, not large margins. Banking and mobile telephony are basically mismatched industries. It would be much more sensible not to make the latter depend on the former.

There is a glimmer of hope that things might change. The central bank’s report recommends the creation of “payment banks,” which can offer payments and remittances but not loans. Mobile operators are expected to apply for licenses. But the banking industry is expected to lobby against them.