Since supermarkets came of age in the 1950s, the American grocery store layout has largely been frozen in time.

And for good reason. Every inch of the traditional track around US supermarkets—from the beautifully lit piles of produce and bounteous bakery section to the inviting prepared foods—has been honed to maximize the grocery industry’s tried-and-true business strategy: Promote the national brands and packaged goods that drive customers in the door, but steer them toward the more-profitable, perishable goods—such as fresh produce—where the supermarket really makes money.

“The outside of the store, the produce, the meat, and seafood, it has much higher margins,” says Euromonitor International analyst David McGoldrick.

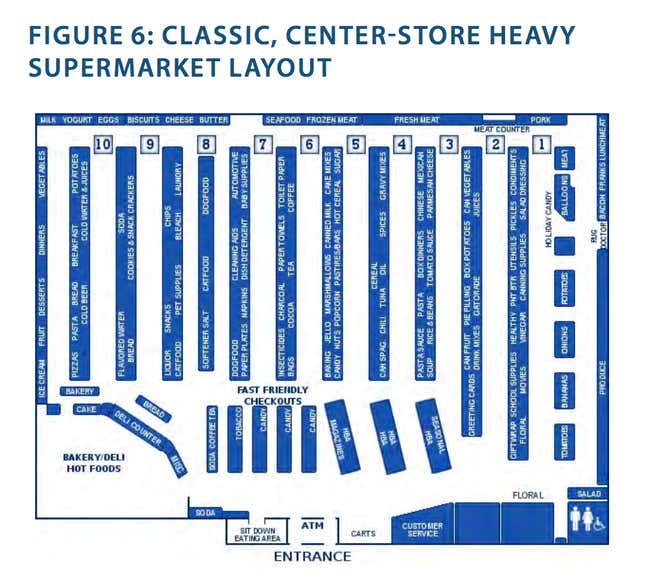

And that’s why grocery store layouts almost always steer shoppers through those hillocks of lettuce and tomatoes immediately upon entering, before they wander off to the “center store” where less-profitable packaged foods are found. That tried-and-true approach has been the unchallenged model of the grocery store business for decades. Here’s a typical “planogram”, in which customers enter but are forced to turn right at the checkout counters, ending up in the produce section:

Until now, that is.

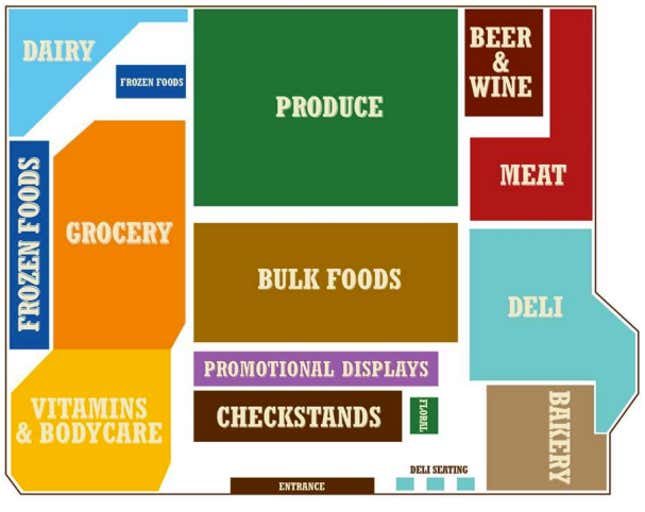

The fastest-growing American grocery store has thrown the traditional game plan out the window. At Phoenix-based Sprouts Farmers Markets, fruit and vegetables aren’t a section through which customers have to be steered; they’re the main draw.

Quite literally, Sprouts stores are built around produce. Unlike almost every other supermarket, Sprouts puts the produce section deep in the back of the store, secure in the knowledge that shoppers will seek it out.

The reason is price. Sprouts’ business is based around aggressively-advertised low prices for produce—20% to 30% below conventional competitors. Those low prices mean high sales volume, which means, faster turnover, which means less waste, which means lower costs, which means the company makes money despite the lower prices.

“Sprouts has essentially flipped the conventional supermarket model, which promotes center-of-the-store grocery products to drive traffic and builds a basket with higher-margin perishables like produce,” wrote Credit Suisse analysts, in a note that referred to the “disruptive” potential of the chain and called it “one of the most compelling growth stories in retail.”

Waste not

In effect, Sprout’s business model is based on the well-known inefficiencies in the way America sells produce. According to consulting firm Oliver Wyman, up to one out of every seven truckloads of perishable food delivered to grocery stores will be thrown out. Perishables make up 80% of the waste at food retailers. In a 2011 paper, USDA economists estimated that $15 billion worth of fruit and vegetables get wasted by retailers annually.

A key source of waste seems to be the the giant piles of produce stores rely on to catch the eyes of customers. These are designed to create a feeling of abundance. But in reality they lead to over-ordering by the store and over-handling by both customers and staffers, and to spoilage when the stuff at the bottom rots. (Interestingly, in its annual report, Sprouts refers several times in passing to its “low displays.”)

Produce pays

Sprouts is projected to add nearly 30 stores this year, and it plans to open more than 1,000 stores over the next decade. It’s not just the fastest growing grocery retailer, but one of the fastest growing stores in any sector in the entire country.

However, right now, Sprouts is concentrated in the Southwest, the produce powerhouse of the country. Its three distribution centers are in Arizona, California, and Texas. Expanding far into other regions could be difficult to achieve with the same pricing and quality. Approximately 46% of Sprouts’ sales—and as much as 70% of its produce, depending on the time of the year—come from California, leaving it potentially vulnerable to weather-related disruption or local economic downturns.

Moreover, the competition is intensifying. Whole Foods, the supermarket chain known for its organic and high-end produce, has more stores across more of the country, and is starting to aggressively invest in bringing down prices. Low-cost giants like Kroger and WalMart are boosting their organic and produce offerings. If Amazon expands its grocery delivery service, Amazon Fresh—currently available only on parts of the US west coast—that would also hurt Sprouts, though according to Deutsche Bank, it has the advantage that people still like to look at and feel produce before they buy, and Sprouts is already relatively cheap compared to Amazon.

Still, Sprouts’ focus on organic and fresh food should help it. ”I think the area that Sprouts and Whole Foods are in the kind of natural and organic market that is going to be one of the biggest growth drivers over the next 5 to 10 years,” David McGoldrick says.

And pricing will probably continue to be its chief advantage. Sprouts doesn’t just undercut Whole Foods, which charges a premium for produce, but even big chains. Consumers are particularly sensitive to price when it comes to groceries in general, and produce in particular, because of how often they buy it. And the discounters and hypermarkets that come closest to competing with Sprouts on price have the lowest quality ratings (pdf).

Sprouts commands less than 1% of US grocery market share, and has barely touched the South, let alone the east coast. Even with stiff competition, there’s plenty of potential growing left to do.