After Tim Cook was inadvertently outed yesterday on a CNBC business-news talk show, (though hardly for the first time), some are calling on the Apple CEO—who has never admitted to being gay, but never denied it either—to come out himself.

And indeed, it might seem strange for someone who heads a company steeped in the ultra-liberal culture of Silicon Valley to stay private about his sexuality. But that’s only because we also intuitively associate the Silicon Valley culture with the 20-something graduates it recruits. And to expect someone like Cook to be cut from similar cloth is to completely ignore where he came from.

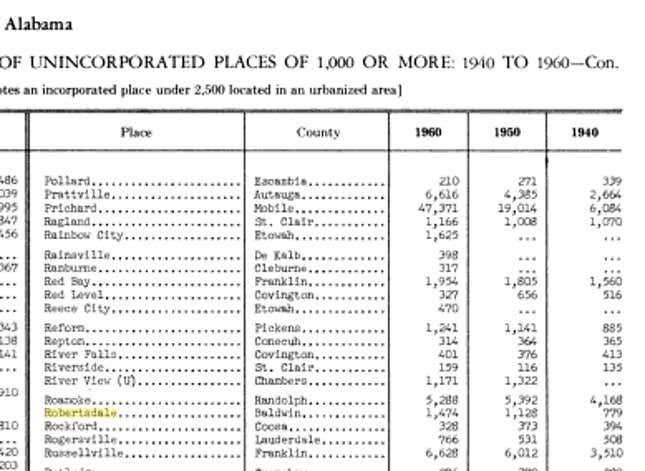

When Cook was born in 1960, same-sex relations were illegal in all 50 US states. His hometown, Robertsdale, Alabama, had just 1,474 inhabitants in that year’s census.

Alabama is one of the US’s most conservative states; it still requires its schools to teach that homosexuality is “not a lifestyle acceptable to the general public” and is illegal in the state. (Technically the ban is still on the books, though the US Supreme Court struck it down in 2003.) In a speech last year at his alma mater, Auburn University, Cook spoke of having witnessed a cross-burning, presumably by the Ku Klux Klan, as a child, and of growing up deeply conscious of discrimination around him.

By the time Cook enrolled at Auburn University—in a smallish city in eastern Alabama—in 1978, the US gay rights movement was well under way. But homosexuality remained illegal in just over half the US’s states, and the activism was concentrated in a few pockets. In San Francisco, a gay activist called Harvey Milk had, the year before, become the city’s first openly gay supervisor (council member). But a few weeks after Cook started at Auburn, Milk and the city’s mayor were shot dead by another supervisor, Dan White. Milk became a gay-rights martyr, but White, notoriously, managed to plead that depression had “diminished his capacity” and get away with a lesser charge of manslaughter, for which he served five years.

The first state to ban discrimination against LGBT people in the workplace—Wisconsin—didn’t do it until 1982, Cook’s last year at Auburn. That was also the year AIDS went mainstream, infecting tens of thousands of gay men and officially being named AIDS; the following year, the influential preacher Jerry Falwell, whose support in 1980 helped Ronald Reagan get elected president, would call it the “gay plague.”

IBM, where Cook went to work upon graduating, adopted an LGBT non-discrimination policy (pdf) in 1984, making it quite a pioneer among big firms. Nonetheless, it wasn’t until 1995—a year after Cook left IBM—that a new CEO, Lou Gerstner, decided that IBM needed to not merely ignore differences but actively encourage diversity, and set up several task forces to work on making minorities, LGBT people among them, feel welcome.

Of course, we can’t speculate on what effect this all had on Cook himself. But it certainly makes it a lot easier to understand why someone with his history might, even today and in Silicon Valley, continue to choose not to shout his sexual orientation from the rooftops.

And as James Stewart, a New York Times columnist, pointed out in a recent article (the inadvertent trigger for the episode on CNBC), most CEOs of the biggest companies are of Mr Cook’s generation or older. So it’s also no surprise that, while the macho but young world of sports is seeing ever more openly gay players, the C-suite is still a closet.