Money: Americans want it again

Nobody has wanted money for a while now.

Nobody has wanted money for a while now.

Want proof? Just look at the price. Interest rates—the price of money—remain at record lows. Simply put, that means the supply of greenbacks is way larger than the demand.

Here’s a look at one of the cornerstones of interest rates: yields on government debt in the US. The yields are the lowest at any time on record — except perhaps in the aftermath of World War II.

Seriously. The aversion to money has been stark. You’d think the global economy was populated exclusively by Weimar-era Bavarian housewives, who saw little use for cold, hard cash—except perhaps as fuel for the furnace.

So what’s going on here? If money is this cheap, why haven’t banks been rushed like a Wal-Mart giving away free waffle irons on Black Friday? The answer has to do with what came before money went on sale. The massive buildup of consumer and corporate debt that burst in the financial crisis resulted in painful losses for both homeowners and financial institutions. The economy went into the tank. Banks grew leery of lending. And consumers and companies had no appetite for borrowing.

Even after the US crawled out of the recession, growth has looked mighty slow. There seemed to be little reason to borrow and invest, even if the thought of borrowing didn’t make corporations and consumers nauseous. According to economists like Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, this is what you’d expect in the aftermath of a financial crisis. And as with any hangover, the only surefire cure is time, and perhaps some greasy food and a jog.

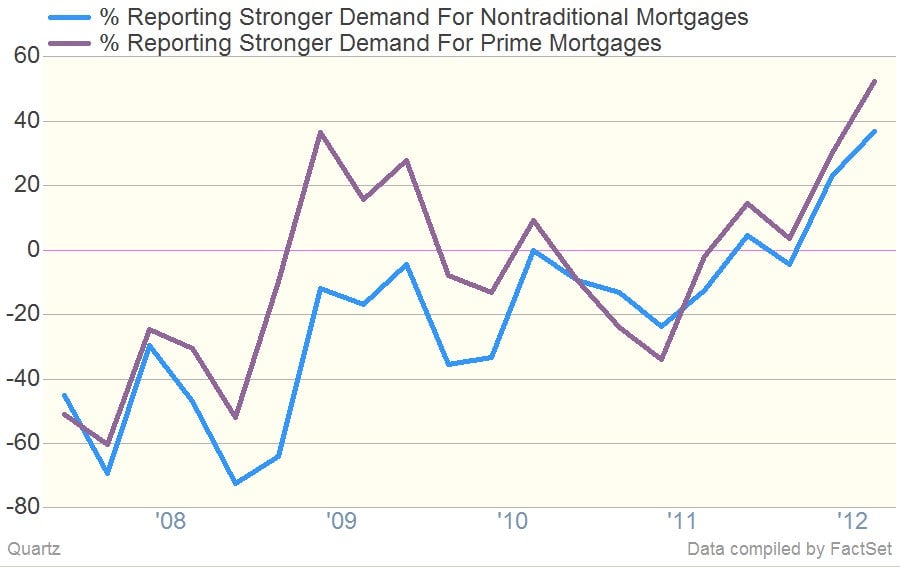

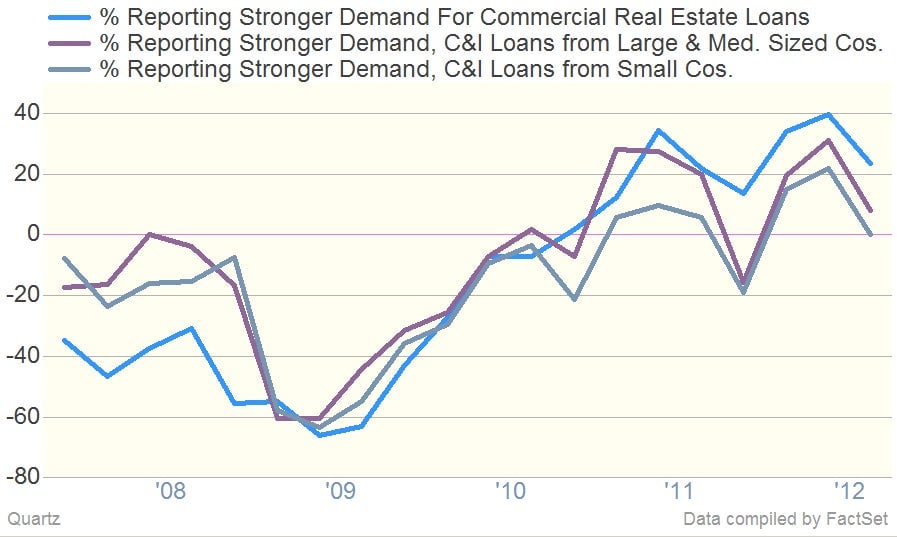

On the other hand, it’s been more than four years since the financial crisis climaxed. And there are some signs that demand for money is starting to pick up. How do we know? Well, the bankers are telling us. Or at least, they’re telling the Federal Reserve, via the central bank’s quarterly survey of the folks that dole out the loans at banks.

Those numbers are clearly consistent with the “rebirth-of-housing” narrative that’s been playing out in the US economy for the last several months. The story for business loans is a little bit more blurry. While demand for commercial and industrial (C&I) loans has improved markedly since the worst of the recession, it’s softened significantly in recent months. And that squares with the “fiscal-cliff-is-creating-uncertainty” theme we’ve been seeing show up in other business investment data lately.

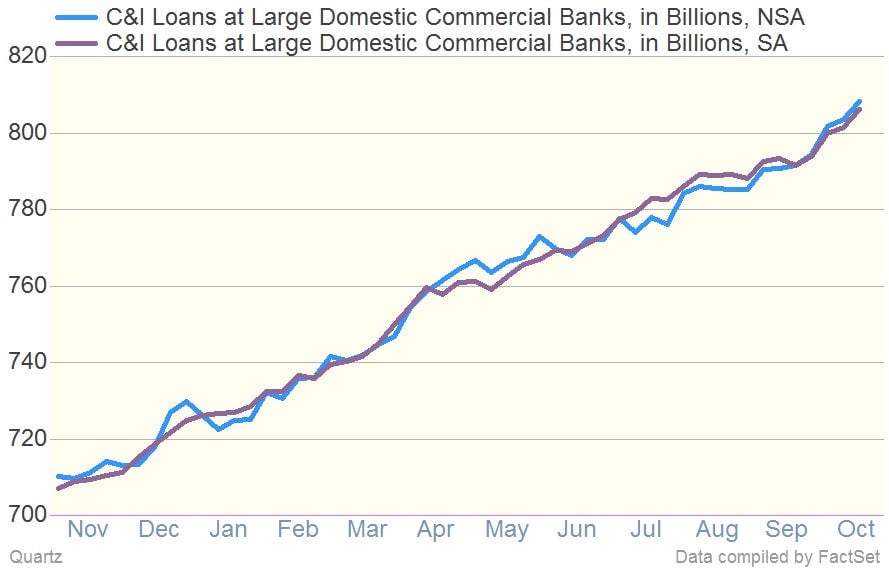

But even so, there are indications that somewhere out there, companies are interested in borrowing. Here’s a look at the amount of commercial and industrial loans that banks have been making. Even the Fed, in its recent lending survey, noted what it called “the brisk expansion in C&I lending at commercial banks over the past 12 months.” Here’s a look at Fed data on C&I loan growth at large US banks over that period. (We’ve included both seasonally adjusted (SA) and non (NSA).)

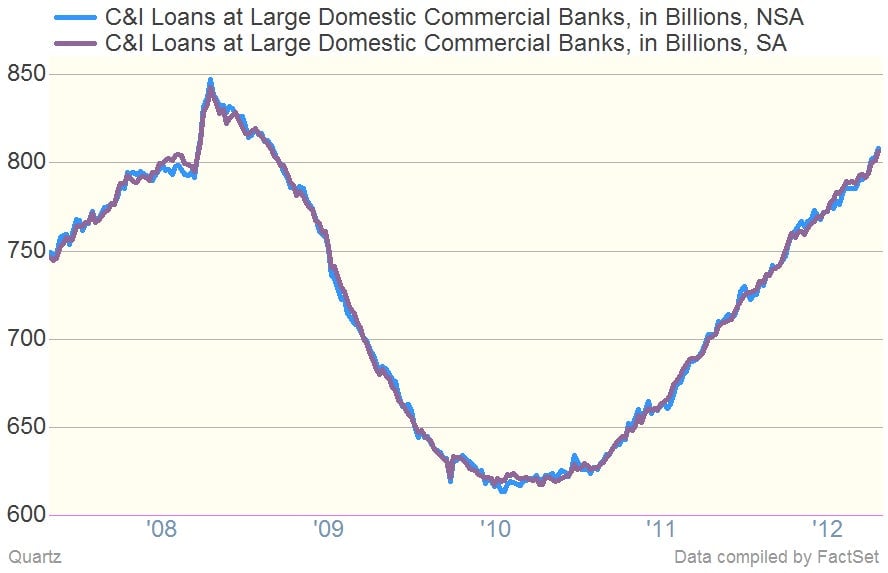

This is significant. Here’s a longer term look at the same data. You can see the marked decline in business lending through the worst of the economic slowdown. And we’ve made real progress clawing our way out of it.

Ok, there are plenty of caveats. For instance, some of the lending in commercial and industrial loans is filling in the gaps left behind by the disappearance of other sources of funding for companies, such as the market for short-term business loans known as commercial paper. But that’s not the bulk of what’s going on. In fact, in its survey US bankers told the Fed that “the replacement of nonbank debt accounted for less than 25 percent of the increase in C&I loans at their bank.”

Here’s the bottom line: Five years after the financial crisis things in the US really starting to return to something like normal. Would-be homeowners are interested in mortgages, which are really cheap. And cash is flowing into the US business sector.

On the business count however, it won’t help the economy much unless these companies actually spend it. And as we’ve seen recently, businesses seem to be in a decided holding pattern until they are confident that Washington wrangling over the fiscal cliff isn’t going to send the country back into recession.