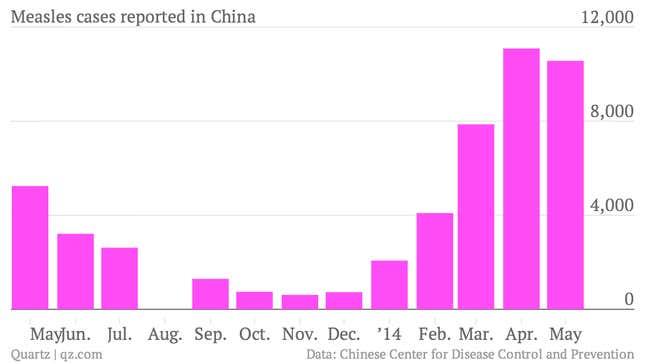

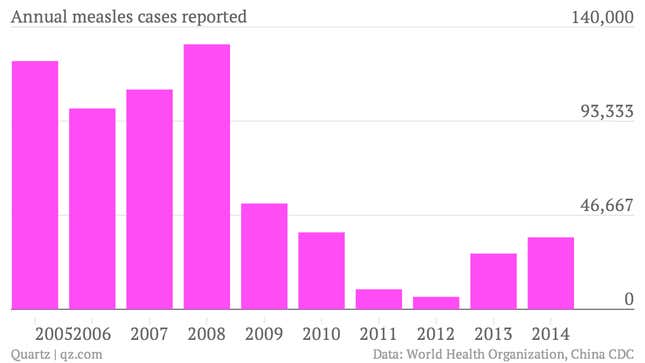

China’s latest push to eradicate measles, started in 2005, has been showing excellent progress in recent years, and experts predicted the goal could reached by 2015. But 2013 saw an uptick in cases, and in recent months there has been a sharp rise, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest statistics show:

In the first five months of 2014, China has reported nearly 36,000 cases of measles, well over the 27,646 cases reported for all of 2013 and almost six times the number reported in 2012.

What’s behind the outbreak? Some experts say China’s nearly 250 million migrant workers, who have moved in recent years from rural areas to jobs in urban centers, and whose families may have missed country-wide vaccination drives because of their nomadic lifestyle. “The incidence of measles is likely to rise, mostly in adults, because China has such a large mobile population and many have missed their vaccinations,” Cai Haodong, an expert in infectious diseases at Beijing Ditan Hospital, told the South China Morning Post.

China’s vast urban migration and industrialization have created mega-cities, where healthcare is generally easier to administer than in the country. At least judging by measles outbreaks, though, when workers bring their families to cities, children aren’t always getting the same health care as other urban residents.

“Migrant children have been at the forefront of China’s measles epidemic,” researchers from the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development wrote in a recent paper (pdf pg. 9). The increase is “likely related to their lower rates of receiving the measles vaccine,” thanks to greater reliance on unlicensed physicians, and the fact that they don’t have permanent residence permits that give them full health care benefits available to other urban residents.

China estimates its migrant workers will swell to 400 million in coming years, about one-third of the current population, but the government has done little to study the health of these workers. The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development recommends that China develop special health care programs, including vaccination drives, for these workers—until it does, measles outbreaks could keep increasing.

Cathy Sizhao Yi contributed reporting.