On Monday, July 7, the street leading up to the Queen’s residence in London turned into a little piece of France. Gendarmes roamed the streets; advertisements for Carrefour, a supermarket chain with no presence in Britain, lined the pavements; trucks full of technicians shouted at each other in French, Gauloises cigarettes hanging from their lips. There were baguettes.

In another time it may have been an invasion. This week, it was the London leg of the Tour de France, which organizers say is the most-watched sports event in the world after the Olympics and the FIFA World Cup. Some 3.5 billion people watch some part of the 4,700 hours of television coverage.

Unlike the other two, the Tour de France does not stay put in one stadium, one city, or even one country. Instead, the world’s premier cycling race covers more than 2,200 miles (over 3,500 km) over two more or more countries and terrain that can be flat, hilly, or mountainous.

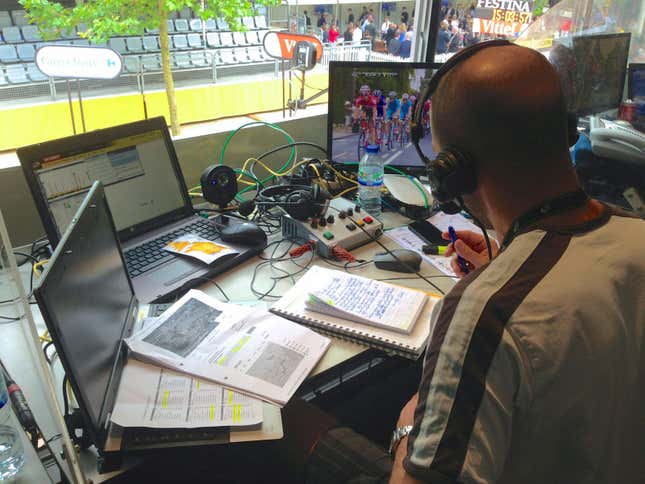

At every stage, a team of technicians must ensure a full suite of communications infrastructure (including superfast broadband) and continuous, robust connections for press, broadcasters, commentators, and event officials. Quartz went behind the scenes at the center of operations for the Cambridge-London leg of the tour, led by Henri Terreaux, the technical director of the event from Orange, a French communications multinational that supplied infrastructure for the event.

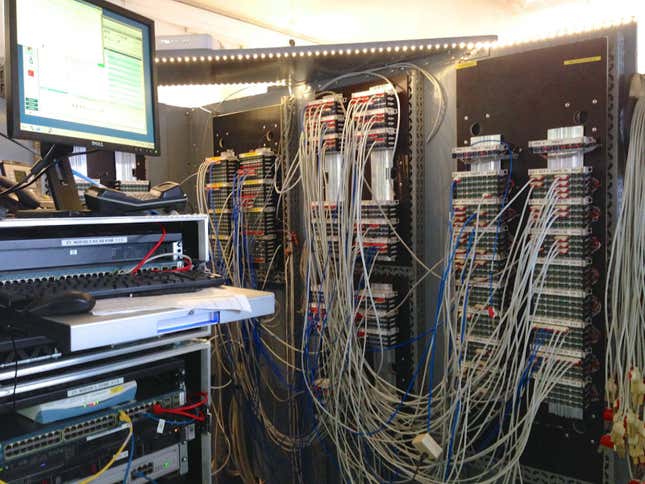

Terreaux leads a team of 50 engineers. Every morning, 25 engineers start building a communications headquarters from scratch, based in four trucks that travel from town to town (the other 25 travel on to the next stage of the race.) One truck is for the press, the second for photographers, and the third for broadcasters. Each is essentially an office on wheels, albeit with broadband connections. The fourth truck is the most important. It is the heart of the communications infrastructure for the world’s media.

Terreaux points to a bank of ports and wires, and tugs gingerly at one. “If I pull that, goodbye BBC,” he says. 70% of all the Tour de France video seen by viewers across the world passes through this one truck. (The other 30% goes directly via satellite.) Putting such a robust system in place—at least when not in France where he can use his own Orange network—involves weeks of planning with the host country’s biggest ISPs.

In the UK, Terreaux is working with BT for fiber-optic connections. In addition to the dozens of fixed-broadband connections, the operation has 500 phone lines and four Wi-Fi hotspots—one each for organizers, commentators, general workers (such as catering), and photographers and broadcasters. The requirements of each are different. Photographers, for instance, need much faster upload speeds than download speeds. One of the trucks carries back-ups of every single piece of equipment, should something go wrong on the road.

What really keeps the show on the road is wires. Lots and lots of wires. His team laid 12 km (7.5 miles) of cabling just on the one-kilometer stretch of The Mall, where the UK leg of the race finishes, Terreaux says, wiping his brow with a theatrical flourish. And there’s loads of spare cable, just in case. Among Terreaux’s biggest worries are the weather, and “trucks running over your cable and breaking it.”