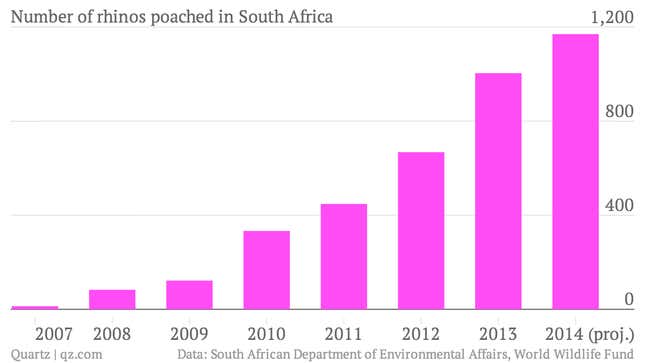

South African rhino poachers have once again outdone themselves. Poachers have killed 558 rhinos this year in South Africa, putting numbers on pace to increase for the eighth consecutive year. The country’s poaching explosion since 2007 is fueled by black-market demand for rhino horns, which can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars each in Southeast Asia—particularly Vietnam, where demand is highest.

A powder made from the horns is prescribed in traditional Chinese medicine to cure fever and convulsions, but the substance is now used as a status symbol and a very expensive way for affluent Vietnamese to cure hangovers or, supposedly, to get high—even though the horns are composed of the common material keratin and have about the same psychoactive effects as snorting a fingernail clipping.

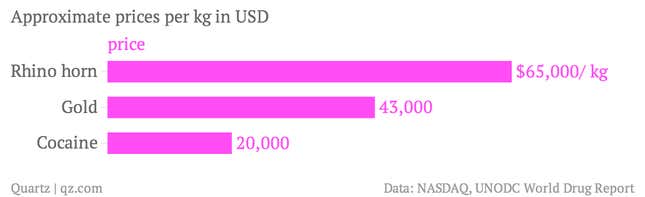

By weight, the horns go for anywhere from $60,000 to $100,000 per kilogram—single horns are about 3.5 kg, on average—making the substance significantly more pricey than other ubiquitous status symbols and intoxicants:

South Africa is home to about 75% of the world’s 29,000 rhinoceroses, but if the country can’t stop the poaching, it may lose that status, said Naomi Doak of the wildlife monitoring network, Traffic.

“We are going to reach the tipping point for rhinos,” she told the BBC. ”By the end of 2014, we’re starting to be in the negative in terms of deaths and poaching outstripping birth, and the population will start to decline very quickly.”

Trade in rhino horn is outlawed by the United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, but some argue that the best way to undercut black market horn trade is to give it competition in the form of a well-regulated, cheap and legal market for cultivated horns. Rhino horns can be removed harmlessly and regrow—so legalizing the trade could facilitate horn farming that doesn’t harm the animals.

Others argue that such an option would encourage misconceptions about the medicinal properties of ingesting the horn and overwhelm the market with demand, allowing poachers to simply coexist with legal trade.

The South African government acknowledges that something has to change. The country’s minister of environmental affairs, Edna Molewa, said that government officials have been meeting to consider “a proposal for the legalization of commercial international trade” to be brought up at the next Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species meeting in 2016.