Earlier this year, a letter to the editor appeared in the back pages of the Journal of Clinical Oncology. In it, Harvard professor Anthony D’Amico points out that, until 2002, the Food and Drug Administration had approved only three medicines for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer; however, in the ensuing 12 years, the FDA has added nine more to its list. Notably, research funding for six of those nine drugs has come from the Prostate Cancer Foundation–an organization founded by a man with prostate cancer.

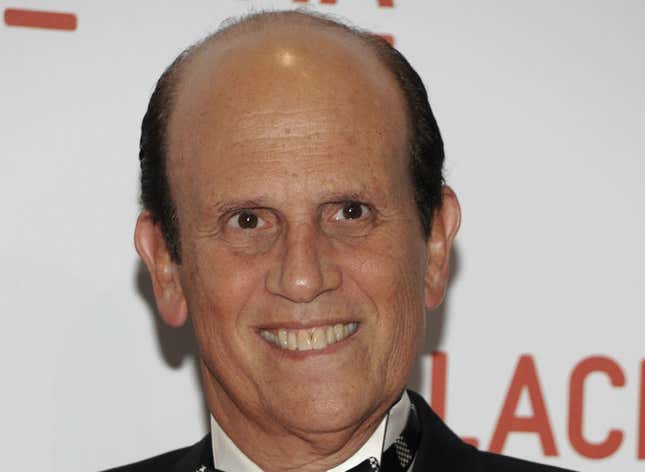

The Prostate Cancer Foundation (originally called CaP Cure) is the brainchild of Michael Milken. I once attended a dinner on the pastoral grounds of Milken’s Lake Tahoe estate, where I schmoozed with Nobel laureates and business legends, including Intel founder Andy Grove. The occasion was CaP Cure’s 2001 annual conference. I was on hiatus from my career as a cancer doctor, working as CEO of a biotech start-up company. We had developed a new kinase-inhibiting drug deemed sufficiently exciting to merit presentation at the meeting. Our drug, however, did not ultimately earn a priority score high enough to secure the “real money” necessary to fuel expensive clinical trials.

After the meeting, I discussed the outcome within our organization as well as with others whose funding proposals had not succeeded. Some advocated for moving on to identify other monetary sources. Others, however, directed their angst toward Milken. “Some altruist,” said one scientist, “The guy gets diagnosed with prostate cancer then desperately hurls his money after a cure for his own disease.”

The personal barb led me to wonder whether qualification as philanthropist must be predicated solely on altruism. It’s difficult to find negative comments about, for example, Katie Couric and her efforts to educate viewers on the subject of colon cancer, the illness to which her husband succumbed and to which her children may be susceptible.

Similarly, it’s nearly impossible to come up with evidence of negativity toward Michael J. Fox and his attempts to encourage study of Parkinson’s disease, the neurological disorder from which he suffers. Or perhaps the ultimate fodder that was never scooped up by cynics, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who as president, created the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to shunt significant federal funds to study polio; the disease that rendered him wheelchair-bound. Still, as chat room banter shows, when it comes to Michael Milken and his organization’s impressive contributions toward curing the disease from which he suffers, resistance persists.

The assertion that Milken’s organization is key to the fight against prostate cancer is unassailable. To date, the foundation has raised more than a half-billion dollars to fund research at nearly 200 academic centers in multiple countries within North America and beyond, including Argentina, China, and Norway. And it might be that a personal investment creates a more effective change. PCF director Howard Soule attributes the organization’s high batting average to its scientific advisory board’s knowledge about prostate cancer’s underlying biology as well as about advantageous ways for meeting clinical needs. He notes that PCF’s scientists look at highly innovative proposals often rejected by more conservative peer reviewers in the National Institutes of Health. Soule told me that they then “relentlessly, even doggedly” keep on researchers to monitor outcomes.

Johns Hopkins urology professor Bruce Trock agrees that PCF is a crucial lynchpin in the fight against prostate cancer. “PCF is the mostly highly regarded entity in prostate cancer science; a fact corroborated by the variety of projects that are brought to them without solicitation, and by the number of talented young investigators whose careers have been jump-started by PCF funding.

Milken is obviously intelligent, with unique talents for evaluating systems and getting things done. But as news archives report, in 1989 Michael Milken was sentenced to 10 years in prison for his involvement in securities fraud. After sentence reduction, he spent two years in jail. What, I wondered, was driving this man? Perhaps a need to further repay his debt to society; or maybe his confinement had provided time for contemplating his life and crystalizing his values.

Whatever his reasons, Milken has directed serious energy to the public good in invaluable ways. In addition to the foundation’s medical research, he has championed numerous causes—most notably education—and engaged others in philanthropy. His generosity has not been without cost. In an argument that would seem to neutralize most critics, Howard Soule points out that,” …in a way, we at the Prostate Cancer Foundation are the suckers.

The value of the intellectual property that underpins these new drugs and the subsequent royalties would be in the tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars if we operated like a for-profit entity.” A glance at the billion-dollar sales projections for just one of their most exciting drugs, Enzalutamide, attests to the truth of Soule’s lament. Yet in some quarters, disparagement of Milken’s efforts continues.

Must we personally like the philanthropist or agree with his or her behavior? Do we expect them to live up to our own moral standards? Are we justified in ridiculing and denying help to countless others because we choose not personally to approve of the helper? Over a decade ago, as a younger (and probably naïve) idealist, I didn’t know how to sort out the dissonance that accompanied me as I departed the CaP Cure convention.

It’s impossible to be certain about what propels someone like Milken. My sense is that authenticity seeps through his generosity, but some will never find forgiveness for a man who, according to James Stewart’s book Den of Thieves once profited as target companies went under, jobs were trashed and personal savings vanished.

Ultimately, it doesn’t concern me whether Milken’s efforts were motivated by altruism, egoism or some synthesis of the two forces. His suffering prostate cancer is not reason to disparage his constructive efforts to cure a disease that hurts so many. We are the beneficiaries of his comeback story that has been greeted with multiple rounds of applause at the Food and Drug Administration. The successful outcomes of the Prostate Cancer Foundation remind us that when it comes to philanthropy, self-interest is not synonymous with selfishness.