Tragedy struck Malaysia Airlines for a second time in five months yesterday, after a flight from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur was shot down in eastern Ukraine, killing all 298 people on board. Even before this latest disaster, questions were already being raised about the airline’s viability—especially in the wake of the March disappearance of flight MH370.

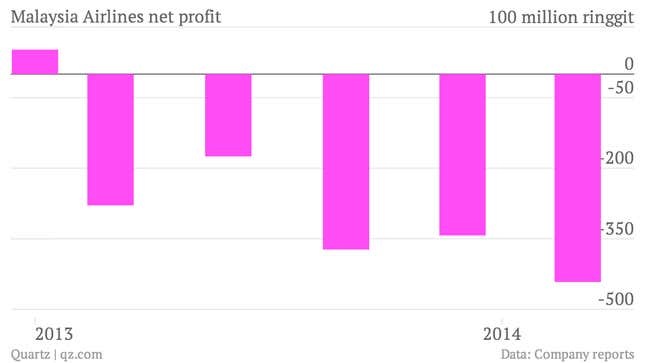

After flight MH370 went missing, the airline reported a first quarter loss of 443 million ringgit ($139 million), versus 279 million ringgit the year before, as passengers, particularly those from China, opted for other airlines and non-Malaysian destinations. The most recent tragedy could depress passenger numbers even further, even though early indications suggest the airline and its pilots were not doing anything that unusual by flying through the area.

Although European and US aviation agencies warned in April that some Ukraine airspace should be avoided, dozens of flights a day were flying through the country’s airspace, according airline analysts, despite the fact that two Ukraine aircraft had been shot down in the past week alone.

“Malaysia Airlines, like a number of other carriers, has been continuing to use it because it is a shorter route, which means less fuel and therefore less money,” Norman Shanks, a former head of group security at airport operator BAA, told The Telegraph. Most commercial airlines fly at heights believed to be too high for military strikes. Right after the Malaysian flight was shot down, flights operated by Singapore Airlines and Kazakhstan Airlines flew through the same airspace, The Telegraph reported.

Whether the airline should have altered its flight plans or not, already-negative sentiment about flying it has turned even darker. The airline is now offering full refunds, even on non-refundable fares, to passengers who want to cancel flights in the next week.

But two tragedies aren’t the only problems Malaysia Airlines faces. Like other flag carriers, it faces stiff competition from low-cost airlines. Malaysia Airlines lost $359 million last year. The loss in the first quarter—while surely worsened by the MH370 disappearance—were its fifth straight quarter of red ink, due in part to a strategy of slashing fares to fill seats.

“MH370 exacerbated an already tough situation and makes it even more challenging for [Malaysian Airlines] to turn around without major changes,” airline analysts CAPA said in May.

Besides driving away potential passengers, the loss of MAS flight 17 could create an insurance quagmire. The airline’s insurer, Willis, should provide coverage and compensation for the value of the aircraft itself, insurance experts say. But the airline is on the hook for $44 million in compensation for the families of victims, and any reimbursement of that figure could be lengthy and complicated, with insurers pursuing the people or groups who shot the airplane out of the sky.

Ultimately, the airline’s woes are the Malaysian government’s problem. It is 69% owned by the Malaysian government through its investment arm Khazanah Nasional. Many investors and former government officials have been pushing for Malaysia to dump its stake, long before the two accidents.

But finding a potential buyer isn’t going to be easy. Etihad, seen as a likely partner, publicly denied reports it could be considering buying an equity stake last month. A tie-up is tough because of Malaysia Air’s grim financial numbers, but also because unions, who represent a majority of Malaysia Airlines 20,000 employees, squashed attempts to partner with discount carrier Air Asia in 2011.