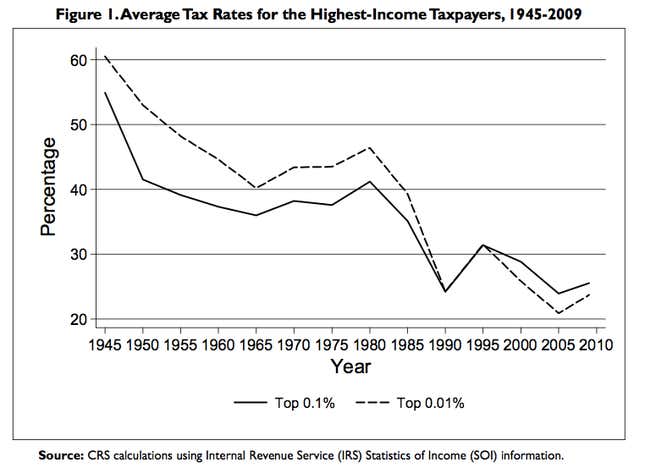

The US Congressional Research Service is normally about as exciting as it sounds: Academics churning out reports for the edification of American legislators. But a recent CRS publication so offended Senate conservatives that they had it pulled from public circulation. The report has been reposted elsewhere, though, so that all may read its shocking finding: contrary to Republican tenets, lowering the tax rates for high earners does not make the economy grow faster.

Coming on the eve of the presidential election, the report’s suppression raised a predictable fuss. But while press coverage has wondered whether attempts to quash it might backfire and draw more attention (well, they did), the findings themselves aren’t even unusual. Yes, the connection between tax rates and economic performance is complex; yes, the Republican leadership complained about the report’s rigor—it doesn’t take policy lag or Federal Reserve action into account—and its language (it referred to “the Bush tax cuts” and “tax cuts for the rich.”); and yes, the idea that higher taxes lead to less work can seem intuitive. Yet the CRS report isn’t the first to show little connection between tax rates and economic expansion. Consider:

- French economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty have done extensive research on American tax policy, and conclude that an optimal tax rate for a country’s wealthiest citizens is between 50% and 70%—far higher than America’s current top marginal rate of 36%. The economists say the data don’t show high earners working less when taxes get to that level, though they do try to lower their tax bills using different financial tools. They note that growth in the 30 years before US President Ronald Reagan reduced taxes from top marginal rates as high as 70% was greater than in the years thereafter. The two even compared tax rates and growth across the 18 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and concluded:

“[T]he bottom line is that rich countries have all grown at roughly the same rate over the past 30 years—in spite of huge variations in tax policies. Using our model and mid-range parameter values where the response of top earners to top tax rate cuts is due in part to increased rent-seeking behaviour and in part to increased productive work, we find that the top tax rate could potentially be set as high as 83%—as opposed to 57% in the pure supply-side model.”

- Bruce Bartlett, who worked on tax policy in the Reagan administration, has also noted little conclusive connection between low taxes and economic growth. He cites a paper by economist Martin Feldstein that found that the 1986 tax reform—the last major rate-lowering overhaul of the American tax code—had little effect on growth. A study of the same episode by Alan Auerbach and Joel Slemrod came to similar conclusions.

- Not all tax cuts are made the same way. If tax cuts aren’t matched with spending reductions, the accumulating debt can be a drag on economic growth. Both Peter Orszag, a former budget chief in the Obama administration, and Glenn Hubbard, a top economic adviser to the Romney campaign, have published research that shows increasing debt from unfunded tax cuts can make new investments prohibitively expensive.

Of course, tax policy can’t be totally disconnected from growth, and it’s not: Loopholes and tax breaks can distort business decisions and shape the economy with unexpected consequences, and tax differences across borders can have significant affects on international capital flows. Changes in how much revenue is taken from citizens affects consumer spending and saving. If the government can’t fund its spending, public debt has consequences of its own. But there’s no hiding the reality that when it comes to growth, the marginal tax rates paid by the highest earners aren’t the high road to expansion.