On a rainy night in September 2007, hundreds of squatters made their way into the third-tallest skyscraper in Caracas, Venezuela, and set up a temporary encampment. The unfinished, 45-story building—intended as a bank headquarters in the center of the capital—had sat vacant for more than a decade, after the developer’s death and the country’s 1994 financial crisis put construction on hold.

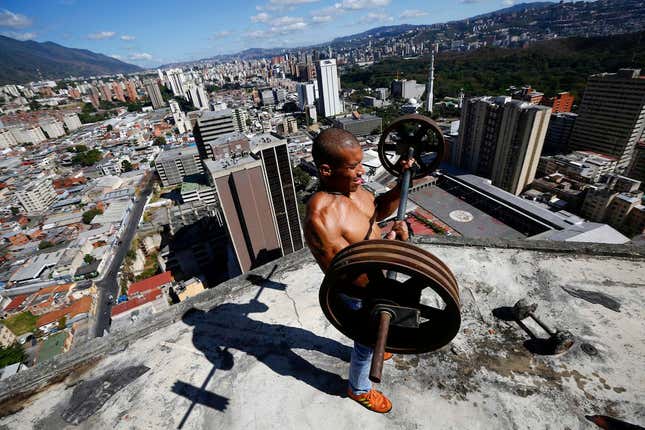

Eventually, nearly 3,000 of the city’s poor—many of them refugees from insecure shantytowns—would join the initial squatters, creating a makeshift city with apartments up to the 28th floor, even though there are no elevators or, in some places, even a facade. The squatters organized their own electricity, running water, and plumbing, along with bodegas, a barbershop, and an orthodontist. The improvised community became known as Torre David, or the Tower of David, after the developer, David Brillembourg.

Yesterday, the Venezuelan government began a long-threatened eviction of Torre David’s residents. They are being relocated to Cua, a small city 40 miles south of Caracas. Local newspapers speculated that a Chinese deal to redevelop the tower was behind the move. China’s president, Xi Jinping, was in Caracas this week to sign oil and mineral deals worth billions of dollars with Venezuela.

The government denied these rumors, citing safety issues instead. Ernesto Villegas, a government minister, told reporters yesterday: “The tower does not meet the minimum conditions for safe, dignified living.” Torre David’s half-finished state has led to accidents (mostly falls), and there were reports of gang violence in its early years.

A brutal, fictionalized version of the tower appeared on the US cable television series Homeland, prompting the New Yorker’s Jon Lee Anderson (who had written at length about Torre David and the economic policies that created it) to note that “In real life, as in ‘Homeland,’ the Tower is a symbol of contemporary Venezuela’s broken dreams and, more pointedly, of the failure of the late Hugo Chávez’s experiment in socialism, which he called his ‘Bolivarian revolution.'”

In a new book, Radical Cities: Across Latin America in Search of a New Architecture, the journalist Justin McGuirk recounts a 2012 visit to Torre David, which he calls a “pirate utopia.” He details some of the systems the self-organized community has put in place: The building’s electricity comes legally from the city’s grid, while an ad hoc water system is pumped from the 16th-floor elevator lobby. Residents are barred from buying or selling apartments, though some manage to. Bodegas have variable pricing because “in a vertical economy reliant on leg-power, there is a premium the higher up you go.”

In interviews with McGuirk, Torre David’s residents argue that for all its obvious faults, the squatted skyscraper is an improvement over the city’s crowded barrios. “Thank God this building is safer than many others,” one says.

And that suggests an obvious problem: clearing Torre David does nothing to address the chronic poverty and housing shortages that led to its establishment in the first place. Though the tower is highly visible, it’s hardly the only informal settlement in Caracas’s downtown. McGuirk counts ”dozens”; Anderson said there were over 155 as of late 2012. That includes an entire shopping mall just two blocks away from the emptying tower.