There has been a lot of recent attention focused on the importance of executive function for successful learning. Many researchers and educators believe that this group of skills, which enable a child to formulate and pursue goals, are more important to learning and educational success than IQ or inherent academic talent.

Kids with weak executive function face numerous challenges in school. They find it difficult to focus their attention or control their behavior—to plan, prioritize, strategize, switch tasks, or hold information in their working memory. As a teacher and a parent, I’m always looking for fun ways to shore up these skills in my students and my children.

I recently reported on the benefits of free play and noted that kids who spend a lot of time in adult-organized and structured activities such as lessons, athletic practice, or highly scheduled camps get fewer opportunities to strengthen self-directed executive function.

Free play is a fantastic default mode for summer, but when the lightning flashes, the thunder roars, and the words “I’m bored” escape my children’s lips, I reach for games. Not the electronic kinds that require a controller and a background check at Common Sense Media—the kind that rattle around in a box and require human interaction and cognitive engagement.

It turns out that some of my family’s favorite games are educational tools in disguise. Dr. Bill Hudenko, child psychologist and assistant professor of psychiatry at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, uses board games in his practice to diagnose and strengthen these much-touted executive function skills. He also encourages parents to play these games with their children at home.

Dr. Hudenko was kind enough to share his five favorite executive function-building games with me, and I recruited my children as unwitting lab rats in a bit of field-testing.

I’m going to start with my 10 year-old son’s favorite game, Swish.

Skills required: Visual-spatial processing, working memory, attention, concentration, processing speed, and impulse control

Swish consists of a deck of transparent cards with circles and hoops in varying colors and positions. The players must look at an array of as many as 12 cards and identify matches, or “swishes,” in which the appropriately colored circles and hoops of two cards line up. Because the cards are transparent, they may be flipped over and rotated to complete a swish. In an email, Dr. Hudenko elaborated on the benefits of Swish for kids with impulse control and working memory deficits:

Children with executive functioning deficits often struggle with the heavy working memory demands of mentally rotating the cards and sequentially identifying additional card matches. This game also is particularly helpful for developing an appropriate balance between impulse control and increasing processing speed as the child is trying to be the first to identify a “swish.”

My 15-year-old son’s favorite game is Quarto! (I believe because he is our family’s reigning champion).

Skills required: Working memory, reasoning, planning, attention, and concentration

Quarto! is played with a board and 16 pieces that each have four different physical attributes: height, shape, color, and indentation or flatness. The object of Quarto! is to line up four pieces that share the same attribute, but that goal is not as simple as it sounds, because you don’t get to choose which piece you play—your opponent does.

Quarto! taxes players’ working memory and attention because there are so many possible configurations of the game pieces. In order to prevent your opponent from winning, you must figure out all the possible winning moves available to your opponent and not give him or her those pieces. While the game is complex in practice, younger children can understand the rules and improve their working memory as they improve. For children who really need to work on their ability to plan and create systems, Dr. Hudenko recommends the following adaptation:

Allow the child to create his or her own system to keep track of which pieces should not be given to the opponent. If the child requires prompting to develop a system, provide her or him with a paper and pencil and suggest that he or she can write down or draw which pieces would lead to defeat if they were given to the opponent. This approach can create a wonderful learning opportunity wherein children recognize the importance of using assistive techniques to compensate for difficulties with executive functioning.

One game that most families have stashed away in a box or trunk is Chess, and it’s a one of the world’s oldest and most popular strategy games.

Skills required: Attention, concentration, working memory, reasoning, planning, problem solving, and impulse control

As the rules of chess are both complex and widely known (or easily searchable), I will skip right on ahead to Dr. Hudenko’s description of the game’s benefits:

Chess requires children to attend to multiple emerging scenarios as they evolve on the board. Advanced players learn to think many moves in advance. Playing chess necessitates the successful use of problem solving, planning, and reasoning skills that are the hallmark of healthy executive functioning. Chess also can provide a platform for teaching impulsive children to slow down and think carefully before acting in a way that leads to the loss of a piece.

For younger children, who may lose patience with the pace or complexity of the game, Dr. Hudenko suggests simplifications such as limiting the way pieces can move around the board. He adds that this can also quicken the pace of the game. And for kids who already know the rules and tend to be inflexible in their thinking, changing the rules can help them adapt to the concept of change.

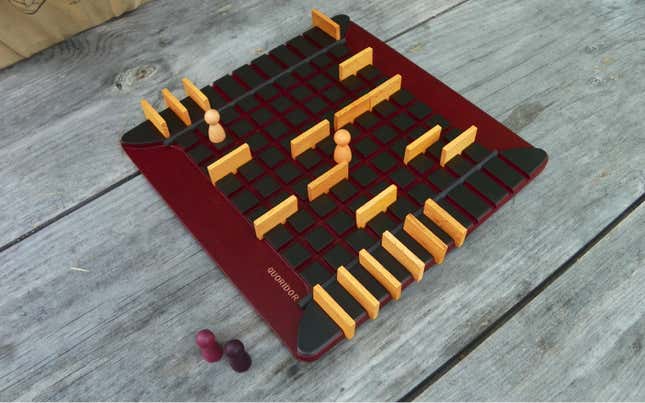

The newest game in our home, but one that has quickly become a favorite, is Quoridor.

Skills required: Reasoning, planning, and problem solving

I like this game because I enjoy switching between a defensive and offensive mindset, and that flexibility is the key to winning Quoridor. The object of the game is to navigate through “corridors” that your opponent creates in order to advance to the opposite side of the board. With each move, a player either moves his or her token or places a piece of barrier that will foil the opponent. Dr. Hudenko explains the challenges inherent in Quoridor’s play:

To emerge victorious, children must learn to carefully observe the opponent’s strategy and thoughtfully plan an effective offense and defense. This game is a good executive functioning challenge because each player is allowed only 10 barriers—which necessitates judicious planning and problem solving to outwit an opponent.

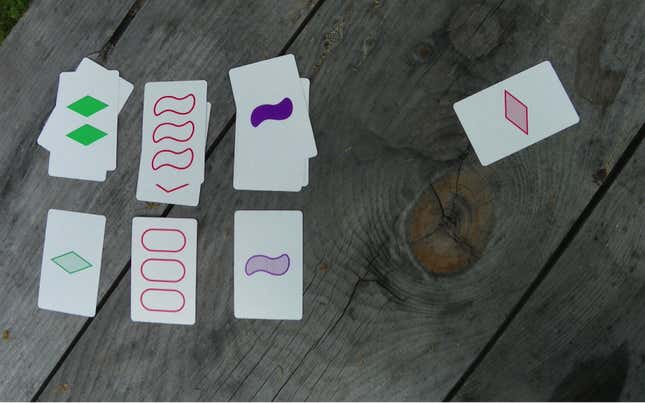

Finally, no article about executive function games would be complete without a mention of Set.

Skills required: Sequential searching, working memory, mental speed, visual-spatial processing, concentration, and processing speed

The goal of Set is, as the name would suggest, to be the first player to create a set of three cards similar in either number, symbol, shading, or color. The rules of the game are simple, Hudenko says, but deceptively so:

Though simple in design, this game requires immense executive functioning skill to search through cards and hold in working memory the specific features that are required for a successful card match.

In my family, we often adapt the basic rules of Set, mainly because some home-grown versions can be played in the car or on kids’ laps. Hudenko explains that one adaptation of the Set rules mimics a popular neuropsychological test called the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), a sensitive measure of executive functioning deficit.

Choose 3 cards that differ across all 4 categories and place them in front of the child. Think of a “mystery matching rule” that will group the cards (e.g., match on color) and help her discover the rule. Give her one card at a time and have her place it next to one of the cards on the table. Confirm whether this match meets the “mystery matching rule,” and continue to work through a process of trial and error with successive cards until the child determines the “mystery matching rule.”

While Dr. Hudenko uses these games to identify deficits in his patients and tax their abilities in order to help them build coping mechanisms, they can help any child (or adult!) become a more flexible, organized, strategic thinker. As an added bonus, these games are fun ways to spend family time together, even if you have offspring like mine; the kind of kids who keep meticulous track of their win/loss records and hold them over your head for all eternity.

This post originally appeared at The Atlantic. More from our sister site:

Disability is not just a metaphor

In a year, child protective services checked up on 3.2 million children