It is common knowledge that research studies have demonstrated the harmful effects of divorce on children. Surprisingly, that common knowledge turns out not to be supported by evidence. Although proponents of marriage would like us to believe that kids with divorced parents have more emotional, academic and psychological problems than they would have had if their parents had stayed together, no credible data exist to back up those claims.

The reason why there is no scientific evidence for the effects of divorce on children is that nobody has ever performed a rigorous study. That is not entirely the fault of the research community, because this turns out to be an extremely difficult question to address.

First, people who get divorced are different, on average, from people who stay married. That causes researchers to compare apples to oranges, which can lead to false conclusions. For instance, parents with low incomes are more likely to divorce than wealthy parents (paywall). Children from poor families also, on average, do worse in school. A researcher could conclude that children whose parents divorce do worse in school and would be statistically correct. The researcher would be just as correct to conclude that children who never vacation in Europe or ski in Aspen are more likely to drop out of school.

If the researcher went one step further and said that divorce causes children to do poorly in school (or that sending a child to Paris will prevent her from dropping out of school), that would be an example of the second problem with divorce research, which is confounding correlation and causation. Our brains are wired to look for causes and effects everywhere. When you hear that children whose parents’ divorce are at increased risk of becoming divorced themselves, do you begin to think of reasons why children would react to their parents’ divorce in that way? Most people do. However, there are many reasons for this association that may have nothing to do with causation.

One simple example is that alcoholics have a heightened risk for divorce, and their children have a heightened risk of alcoholism. If mom is an alcoholic and divorces, and her daughter Olivia is also an alcoholic and divorces, can we conclude that Olivia’s parents’ divorce caused her divorce? It seems just as likely that alcoholism (or some other trait that runs in families) contributed to both of their divorces. Separating causation from correlation is impossible when there are so many factors that contribute to both divorce and the success and well-being of a child, and when most of those factors can’t be measured or quantified.

The complexity of factors that contribute to outcomes for children also leads to a third problem with divorce research. To tease out the effect of divorce from the effects of poverty, genetics, mental illness, neglect or abuse, and many other things nobody even thinks to measure, researchers would need to study far more children than has ever been done before. Studies that claim to have found an effect of divorce on children report tiny effect sizes, on the order of one-quarter of one standard deviation. To put this in perspective, imagine that a study revealed that men who live in Boston are tall, whereas men who live in New York City are of average height. The difference between the two groups of men is one-quarter of one standard deviation. That means that the average man in New York is 5’10 inches tall, whereas the average man in Boston is 5’10 and three quarters inches tall. When you meet a man who is 6′ tall, can you predict with any reasonable certainty whether he is from Boston or New York? Of course not. Even if the studies that purport to find negative effects of divorce on children were confirmed with much larger sample sizes, when you see little Jackson running around screaming and whacking other children on the head while little Noah sits calmly reading chapter books, you could not possibly predict which boy has divorced parents.

How could anyone properly study the effects of divorce on children? The best solution would be a large, randomized study. Researchers would need to randomly assign tens or hundreds of thousands of married parents to two groups, one where everyone gets divorced and one where everyone stays married. Imagine participating in a trial where you were told, “You will get an envelope in the mail, selected at random, that will tell you whether you need to get divorced next week or whether you must stay married for at least the next five years. Then we will test your kids every year to see how they are faring.” Even if you were willing to participate, there is not enough money in government or private foundation coffers to pay for such a study. This is why no reliable studies about the effects of divorce on children exist.

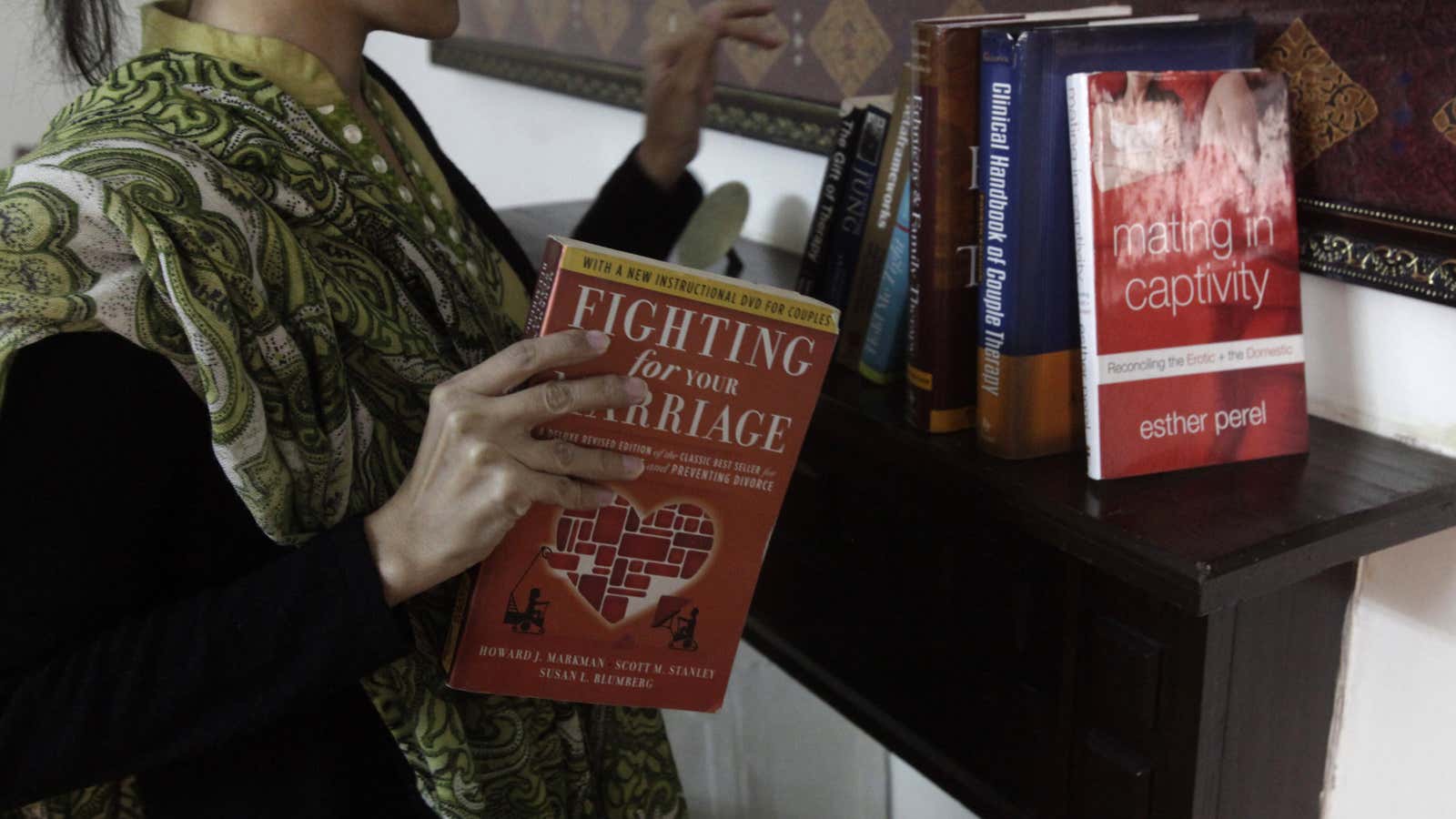

Of course, nobody needs a scientific study to tell them that divorce is painful. Divorce is upsetting to children, and some grow up to feel that they are emotionally crippled because of their parents’ divorce. Even children who view the changes resulting from divorce as positive still have to suffer through the upheaval of changing family structure. Parents should be encouraged to make every effort to mitigate the pain for their children.

What parents should not be told is that their children’s long term happiness and success will be jeopardized if they divorce. This adds unnecessary guilt and grief to a process that is already excruciating. There is no evidence that divorce meaningfully impacts the sort of adult a child will become. Moreover, even if good quality studies existed, decisions about divorce need to be made based upon all of the individual details of each situation, not based on some faulty notion of the law of averages.