This post has been corrected.

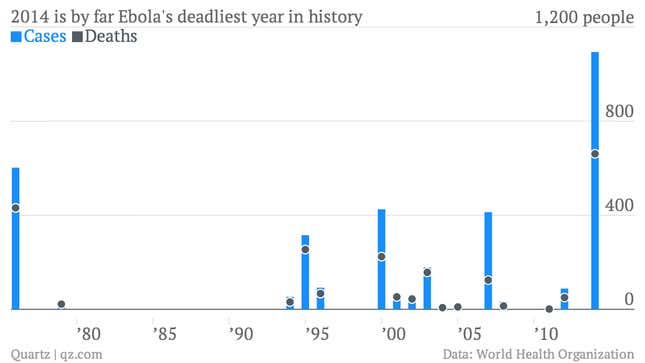

Since it claimed its first victims in Guinea last March, the Ebola virus epidemic has killed 660 people in three countries and infected nearly 1,100—more lethal than any other outbreak in the virus’s nearly 40-year history.

But last week’s developments could transform this outbreak from an unusually nasty regional epidemic to something much bigger. On Jul. 24, Nigerian authorities confirmed that a Liberian man, Patrick Sawyer, had collapsed in Lagos after flying there from the Liberian capital, Monrovia, and tested positive for Ebola; Sawyer died on the night of July 24-25.

This is alarming. So far, Ebola has been confined to Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia—war-torn and largely rural west African countries. But Lagos is different; not only is it Africa’s biggest city, with 21 million people. It’s also one of the world’s most densely populated. And perhaps scariest of all, it’s a center for international travel—meaning that if it’s not contained, the virus could easily go global. Sawyer’s was the first-ever recorded case of Ebola in Nigeria, according to the Nigerian Tribune.

So far, the Nigerian government’s efforts to contain it inspire little confidence. The World Health Organization says that Sawyer, who worked for the Liberian finance ministry, turned himself in to Nigerian health authorities after he began vomiting and having diarrhea in the middle of the three-hour flight from Monrovia to Lagos. Nigeria’s health minister says authorities are currently trying to track down an unspecified number of the 100 or so other passengers on the flight.

This might be tricky. The 35 Nigerian co-passengers took flight once word got out that the health ministry was supposed to have quarantined them, prompting the federal government to launch a manhunt to track them down, reports Sunday Newswatch, a Nigerian newspaper, citing a federal security agent. The government has only now begun screening passengers arriving from foreign countries for the virus, according to the Tribune.

One of the problems for airport screeners is that the first signs of Ebola, which is thought to be spread by bats, are a jumble of flu-like symptoms (e.g. headache, fever and stomach pain). “Unfortunately the initial signs of Ebola imitate other diseases, like malaria or typhoid,” Dr. Lance Plyler of the aid organization Samaritan’s Purse told the Associated Press.

Those symptoms soon become more noticeable, giving way to vomiting and diarrhea. Within a week, the sickened often begin bleeding from mucus membranes, particularly from the intestines. Victims die when internal organs begin shutting down; Ebola typically kills nine-tenths of those infected.

Causing its victims to spew mucus and blood helps Ebola enter the mucus membranes or cuts of its next host. It’s devastatingly good at this. Though medical workers are usually swaddled in biohazard gear, it’s still infected some 100 health workers. So far, 50 have died, including a prominent doctor.

Given that deadly efficiency, the fact that at least 35 people who might have been exposed are at large in Lagos—to say nothing of the other passengers arriving from infected areas of West Africa—is disquieting as well. Confined by geography, the built-up areas of metropolitan Lagos now have more than 20,000 people per square kilometer (53,000 per square mile)—about the same urban density as Dhaka or Mumbai. It has among the highest prevalence rates of open defecation of all major African cities, as well as some of Africa’s lousiest healthcare infrastructure.

Updated on July 28, 2014, 1pm (EST): A previous version of the headline of this piece misidentified Lagos as Nigeria’s capital instead of Abuja.