This post has been corrected.

On Jul. 17, Australia scrapped its carbon tax—hardly a surprising move given that the country’s prime minister, Tony Abbott, once called evidence of climate change “absolute crap.”

Australia’s winemakers, however, don’t seem to agree with Abbott. Several leading wineries are investing in Tasmania, a cooler island state 240 kilometers (150 miles) south of continental Australia. Wine production there is now growing nearly 10% a year, reports the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, while production for the country as a whole is expanding at an average of about 1% a year since 2009.

It’s not just Australia, though. Traditional winemaking strongholds like Tuscany and South Africa will soon become too hot for grape-growing. In fact, by warping the flavors of the most popular varieties and driving production away from the Earth’s poles, climate change is threatening to remake the entire $30-billion global wine industry (pdf, p.14).

Does that mean a “grape-ocalypse” is upon us? No. But it does mean the wine you sip a decade or two from now will taste very different from today’s tipple—and will be a lot pricier, too.

The “good problem”

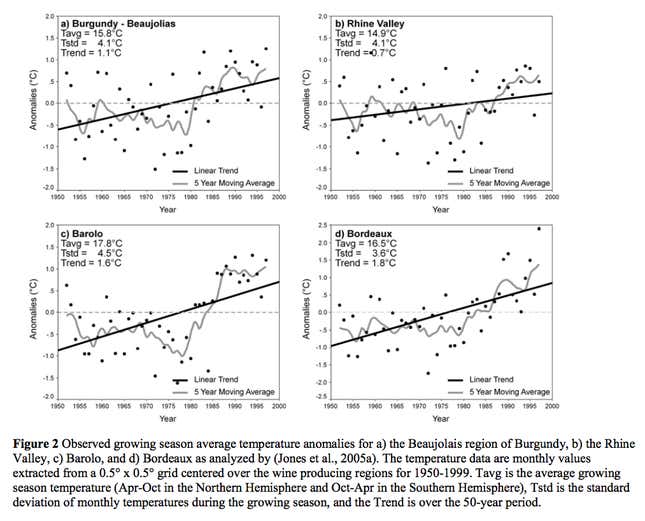

While politicians like Abbott might debate whether the climate is changing, to winemakers, it’s been undeniable. So far, though, it’s mostly been a boon. Warmer temperatures have improved ripening, boosting quality of wine (pdf, p.98) and increasing yield. This is why in Bordeaux, for example, winemakers refer to climate change as the “bon problème.“

Why California wines get you drunk faster

It’s also been responsible for the shift toward bolder-tasting wines that pack a boozier wallop. As grapevines photosynthesize, they create the sugars, which in the fermentation stage, are what yeast converts into alcohol. Thanks to extra sunshine, some Bordeauxs now contain around 16% alcohol, compared with 12.5% in the early 1980s. Zinfandels, meanwhile, have gotten around 30% more alcoholic since 1990. And in the US, at least, this trend might be even more pronounced; one study found that Californian wineries consistently understate the alcohol levels (pdf) of their wine.

But eventually, too much is too much. Stiffer wines are not necessarily a good thing for sales, though, says Alois Lageder, an Italian winemaker.

“[T]he alcohol level is so high that you have one glass and then you’re done. Any more and you will be drunk,” Lageder told Wired. “In Europe, we prefer to drink wine throughout the evening, so we favor wines with less alcohol. Very hot weather makes that harder to achieve.”

Sweetness vs. acidity

They also just don’t taste all that great. To offset sweetness, wines need acidity, the tangy bite that helps cuts the fatty taste when you eat steak. Grapes get that flavor when cool evenings slow the speed at which it metabolizes acids. Brisk weather also promotes anthocyanins, which give wine both its red hue and its astringency. That’s why cooler night temperatures are a big factor in determining wine quality.

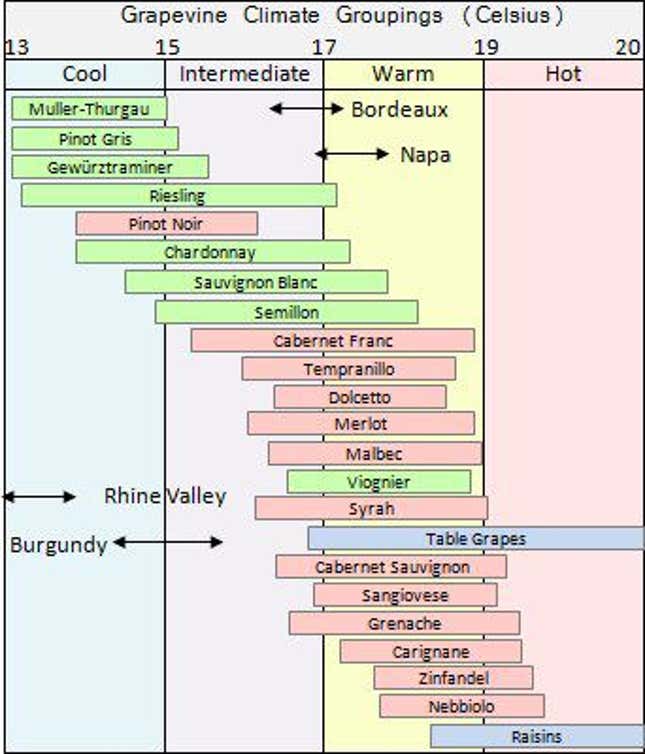

It’s also why wines from cooler climes—Pinot Noir, for example—tend to be more acidic and less alcoholic. And why Shiraz, Zinfandel and other grapes grown closer to the equator tend to be sweeter, fuller-bodied and more liable to put you under the table.

Those more delicate grapes are getting harder and harder to grow. And even in California’s Napa and Sonoma valleys (pdf), where average temperatures haven’t risen excessively, nighttime temperatures are increasing much more quickly.

To prevent sugars from overwhelming the acidity, some wineries now pick grapes up to a month before they would have a century ago. The problem that warming temperatures presents is that if you pick grapes too early, they’ll be bland.

The “hot limit” pushes wineries to the poles

Then there’s what’s called a grape’s “hot limit“—when vines go dormant to try to conserve water, shutting down photosynthesis. If temperatures then rise further still, the grape enters thermal shock, which can ruin its flavor.

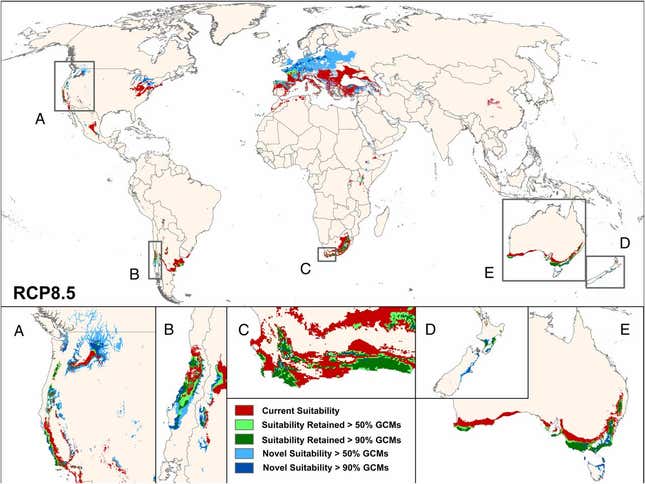

Some regions are starting to get alarmingly close to those limits. In fact, by mid-century more than four-fifths of the land in France, Italy and Spain that’s now used for vineyards will be producing grapes unsuited for wine, according to a 2013 study. Australia stands to lose up to three-quarters of its currently viable vineyard land; California’s looking at a 70% decline.

Machine-gun hailstorms and other freak weather

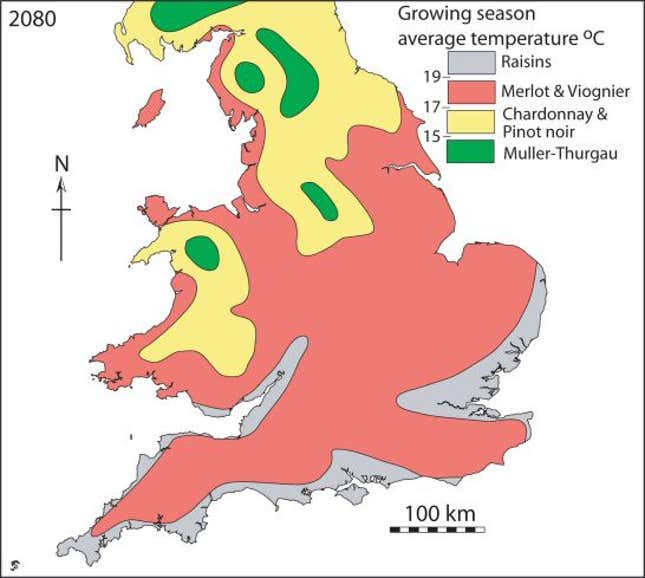

As that happens, cooler areas—places like Germany, New Zealand, Argentina, southern England, and the US’s Washington and Oregon—will experience the bon problème.

But even the new “winners” of this global shift can’t avoid the impact of weather patterns caused by climate change. At the extreme end of that trend are increasingly frequent freak whips of weather like this hailstorm that “machine-gunned” Burgundy vineyards in Jun. 2014. This can devastate a vineyard; for instance, in Napa Valley, replanting a single acre of vines can cost between $15,000 and $25,000. These cause much bigger swings in a wine region’s output from year to year than the industry currently sees.

The cost of adapting

While there’s little winemakers can do to brace for hailstorms, preparing for hotter weather is increasingly necessary. For instance, in Tuscany losses could be as much as 70% as soon as 2020, according to one study. Other research found that if Australian vineyards do nothing at all, they would see gross losses of up to 25% by 2030 (pdf).

2030 might seem like a ways off, but the nature of viticulture means wineries have to start planning now. Since vines can live more than 25 years, those planted with only 2014’s conditions in mind will see returns on those investments dwindle as temperatures rise. Already, some are implementing new planting methods that shield their grapes from the sun. Meanwhile, winemakers that once tried to maximize sunlight are increasingly growing in the shade to try to keep their grapes from frying.

Bye-bye, Pinot Gris—and hello, Merlot

But many are simply replacing vines with those that thrive in balmy temperatures. That explains the surge in Tempranillo production and other grapes that take to heat, including Syrah (a.k.a. Shiraz), Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot. If that trend continues, those varieties will start replacing grapes now grown in colder climes. White wines are particular trouble since the skins of their grape varietals don’t handle heat as well.

The new New World

The surest—but most expensive—hedge against climate change is probably what’s happening in Australia: moving production somewhere cooler. Already, leading Spanish winemaker Bodegas Torres is moving vineyards from the central valley to the mountains. And French champagne-makers are buying up land in southern England.

As they set up in those newly suitable regions, both established wineries and independent entrepreneurs will shoulder the heavy startup costs entailed in starting making wine from scratch (to say nothing of the financial burden that mounts before it’s good enough to start selling).

These are costs that wine-drinkers will ultimately swallow. Of course, climate change probably won’t make all wine more expensive. We can probably expect that hot-climate varieties will stay affordable thanks to extra supply. And perhaps fruity, super-boozy wines will become cheaper too. But wines with subtler flavor profiles will be pricier to make—and will therefore cost more, too. Of course, a pinched wine budget is hardly the scariest thing about climate change. Then again, if you ever needed an excuse to splash out on a Margaret River cab, this is probably it.

Correction: Aug. 3, 2014, 10:30pm (EST): The original version of this story mistakenly featured the chart from Gregory V. Jones’ research paper, “Climate change: observations, projections, and general implications for viticulture and wine production,” showing the modeled growing season average temperature anomalies for the Beaujolais region, Rhine Valley, Barolo and Bordeaux instead of the observed growing season average temperature anomalies.