For those of us with a fondness for profanity, testing the bounds of cursing in the workplace can feel at once satisfying—and fucking terrifying. But fear not, there’s reason to believe that indulging your impulse to drop an f-bomb in the office is worth it, according to some experts. Here’s why:

Everybody’s doing it

Modern media tell us that workplace swearing is cool. Take Martin Scorsese’s latest movie, The Wolf of Wall Street, whose brash yet professionally successful characters dropped 506 f-bombs, a record for a feature film. In a 2006 survey by Associated Press/Ipsos (pdf), 74% of Americans said they encountered profanity in public frequently or occasionally and 66% said that as a rule, people curse more today than 20 years ago.

There are some prominent examples. After the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, US president Barack Obama famously commented on the Today show that he’d been talking to experts about the spill to figure out ”whose ass to kick.” T-Mobile CEO John Legere, a renegade executive known for his potty mouth, badmouthed competitors AT&T and Verizon at a recent press event by saying that ”the fuckers hate you.” Former Yahoo CEO Carol Bartz once told her staff at an all-hands meeting that she’d “dropkick to fucking Mars” anyone whose company gossip ended up on a blog (which her comments promptly did).

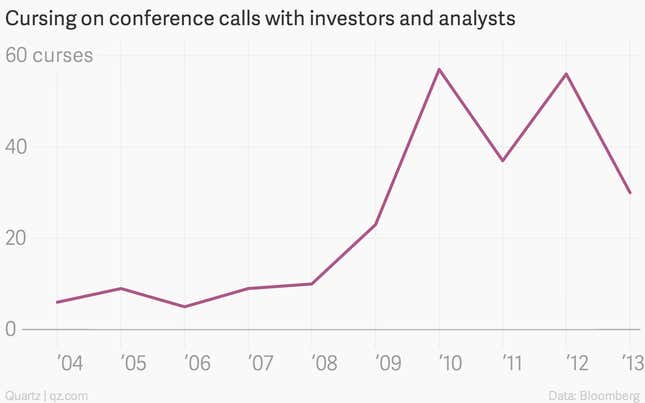

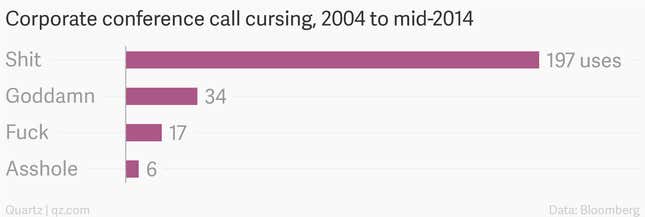

A Bloomberg analysis of corporate conference calls over the past decade found that CEO cursing spiked after the 2009 recession—when the shit hit the fan—and dissipated with the recovery. Apparently “shit” was by far the most popular swear word, used more than ten times as much as “fuck.” (Bloomberg abbreviated these to S, F, GD and AH.)

Earlier politicians and business leaders weren’t necessarily better mannered. But they did have fewer of their words recorded, and what went on the record was often polished for the sake of politesse. Jack Garner, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s vice president from 1933 to 1941, once said the job of VP was “not worth a pitcher of warm piss” and was incensed when newspapers changed his last word to “spit.” The language-scrubbing died down as the recording of speeches and interviews became commonplace.

It’s better than punching someone

Physical violence is never the right answer in the workplace, no matter how bad things get. But in certain contexts, the occasional swear word can be an effective way to manage frustration and diffuse tension. Research has even found that unleashing a cathartic bout of expletives can reduce physical pain, so long as you do it sparingly (the more you swear, the less effective profanity becomes as a coping mechanism). Cursing appears to elicit a fight-or-flight response that releases pain-diminishing endorphins, according to Richard Stephens, a senior lecturer in psychology at Keele University in the UK. It’s ”not necessarily a negative thing,” Stephens has said of his findings on swearing. “It can be a linguistic tool when dealing with frustrating events.”

It boosts leadership

The key to effective workplace swearing is to appear relatable. In an interview with Business Insider, T-Mobile’s Legere said he uses profanity to connect with his employees and customers and come across as an everyman. “I don’t walk closely up against the line. I ignore it. It’s who I am,” Legere said in the interview. “I may be a little rough and crude, but I’m much more like my customers and employees than I am an executive. I think employees relate to the way I speak, customers relate to exactly the way I think and talk.”

Using swear words at choice moments can produce an “emotional wallop” that’s missing in tamer words, Robert Sutton, an organizational psychologist at Stanford University and the author of The No Asshole Rule, told NPR. A 2006 study by Northern Illinois University that asked college students (pdf) to evaluate two five-minute speeches on the merits of lowering tuition fees—one that was PG-rated, and the other with swear words—concluded that swearing made speakers appear more human and hence more credible. Such was the case when Obama swore in his interview about the BP spill; commentators praised him for using language that showed he cared (paywall).

It empowers women

According to the Harvard Business Review’s Anne Kreamer, swearing helps women to penetrate male-dominated networks. A senior female attorney once told Kreamer, “Swearing gives men and women reciprocal permission to feel comfortable sharing revelations.” Similarly, a study from the UK’s East Anglia University found that women tend to swear more around men as a way to assert themselves and turn the tide in male-dominated conversations.

Why? Perhaps because in some cultures, taboo language has given men power, according to Melissa Mohr, author of Holy Sh*t, a Brief History of Swearing. Based on research into ancient Roman society, Mohr’s book argued that, even though women swearing in public is more recent, profanity has historically been linked to sexuality and social order. She documents how men in ancient Rome were put into “active” and “passive” categories, and profane words invented solely for “active” (read: dominant and virile) men to use on “passive” ones. The holdover of that in the modern day, argues Mohr, is that many swear words still reference sex or the body.

If public swearing is effective for women, it is also risky; it can be judged more harshly than for men. Elizabeth Gordon, who researches speech and gender stereotypes at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, has found that foul-mouthed women in New Zealand were judged to be of lower social and moral strata.

But it isn’t for everyone

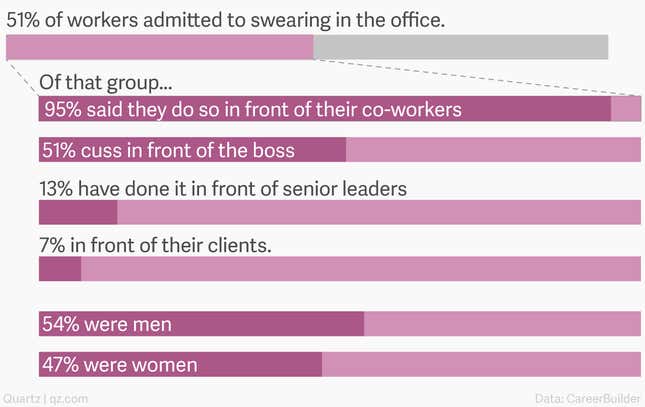

All this doesn’t mean you should just let rip some juicy expletives the next time you walk into the office. As with so many things, good execution is key. In the wrong context, swearing can sully a worker’s sense of professionalism, self-control, maturity and intelligence, according to a recent CareerBuilder survey. It found that 64% of employers thought less of an employee who repeatedly used curse words, and 57% were less likely to promote someone who swears in the office.

But even if swearing now seems ubiquitous, whether it’s appropriate for the office depends largely on the audience and the delivery. In more casual offices—the kind littered with Silicon Valley-esque hoodies and KIND bars—dressed-down language may not only be accepted but celebrated. In a place that’s more conservative or service-oriented, however, it may be wise to tread lightly.

So if you want to give your profanity an airing, spend some time observing your new office first. For instance, the practice is rife at talent agencies, management consultancies, investment banks, media businesses, heavy manufacturers and movie studios, according to the Wall Street Journal. In government, retail, and human-resources jobs, for example, it might not go down so well. And it depends on geography too. A British advertising executive told the Journal that cursing helped define his career because “everyone swears.” After moving to an ad agency in New York, where he discovered bad language was a turnoff, he quickly toned it down.

As for Carol Bartz, after being fired from her post at Yahoo, she told the Wall Street Journal that the one thing she would have done differently was not use the f-word (paywall) during her tenure. She contrasted this with her previous post as head of Autodesk, where she claimed her use of profanity energized employees. Four-letter words “show passion and commitment,” she said. Staffers there “loved me.”

But bad habits can be hard to break. Fresh from being fired, Bartz told Fortune, “These people fucked me over.”