The Ebola pandemic plaguing Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia got more international attention this week, when two American medical workers fell sick and details emerged about the Ebola patient who died in Lagos, an international air travel hub.

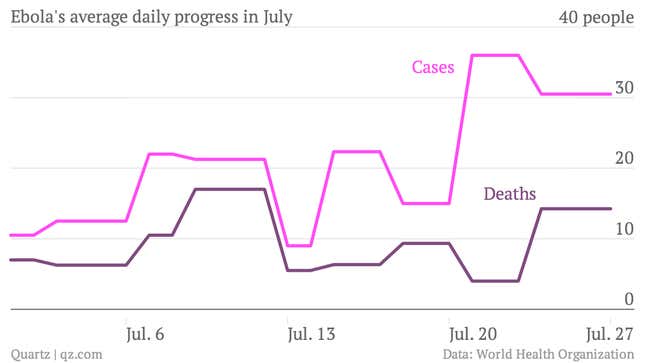

But perhaps the scariest news comes in the latest Ebola data from the World Health Organization. Between Jul. 24 and 27, Ebola claimed 57 lives and infected 122 people. The virus’s spread has been gaining speed:

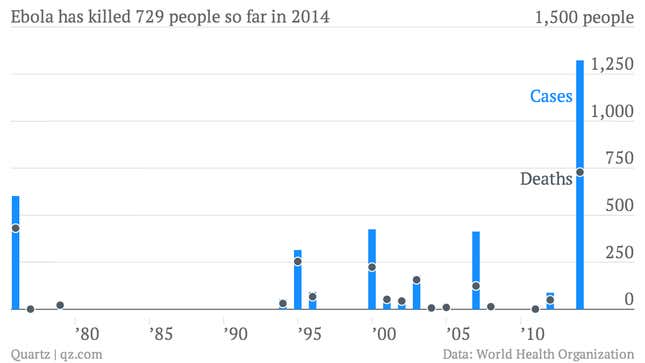

That brings the body count to 729 people, with more than 1,300 infected. To put that in historical context, those killed and infected by Ebola in 2014 alone account for one-third of the total deaths and infections in the 20-some outbreaks since 1976. And it’s only August; the head of the US’s Centers for Disease Control says the outbreak will rage for another three to six months.

This is scary because, as viral public health menaces go, Ebola should be easy to contain. Unlike airborne viruses like, say, swine flu, it’s not exactly sneaky. Ebola is spread only when infected bodily fluids come into contact with someone’s mucus membranes or open cuts. And it tends to broadcast the risk of infection pretty clearly; the symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea and, in some cases, hemorrhaging of mucus membranes.

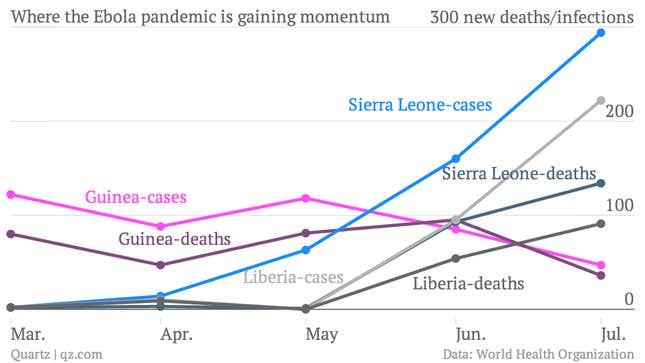

That made Ebola relatively easy to contain when it flared up in remote forests of central and eastern Africa, which are sparsely populated. But this new pandemic is a totally different story:

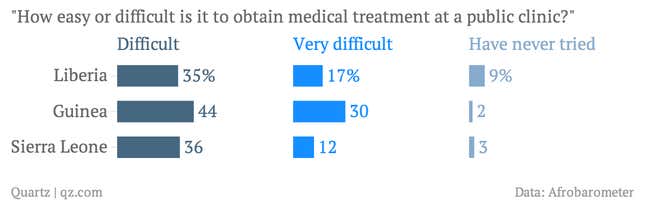

Why is that? For one, Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia all have dreadful medical infrastructure. Sierra Leone has a single laboratory capable of Ebola testing. Earlier this week, Monrovia, Liberia’s capital, ran out of hospital space to quarantine Ebola patients. And that’s in its biggest city, where infrastructure is most robust. In other parts of Liberia, as well and in Guinea and Sierra Leone, hospitals simply aren’t available, according to data from Afrobarometer, a survey group.

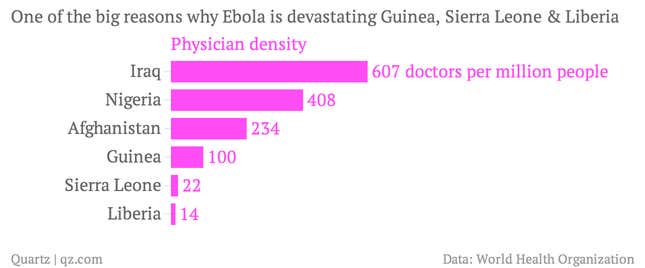

There are also nowhere near enough doctors to go around, and they are at high risk of infection; Ebola has already killed two of the region’s most prominent doctors. That fact hasn’t escaped the notice of local residents, many of whom, thanks to a lack of public awareness about the virus, blame doctors for Ebola’s spread.

Simply put, West African governments don’t have the money or staff to keep their people healthy. That’s why the work of non-governmental organizations like Doctors Without Borders, which has treated a majority of Ebola patients, and Samaritan’s Purse (two of whose workers are now infected) are so vital.

But even their work hasn’t kept infection rates in check. Fortunately, WHO head Margaret Chan just vowed to throw an extra $100 million at the pandemic. The US is upping aid as well, and will dispatch 50 more health workers to affected areas.