It was hard to find water in Toledo, Ohio, this weekend.

The source of northern Ohio’s water the scarcity comes from further north: the green slick covering Lake Erie. It may look no more pernicious than a wheat-grass smoothie, but this bloom of green-blue algae, or cyanobacteria, is toxic enough that it can damage humans livers and other organs (pdf, p.9) and sometimes kill pets. Since some half-a million people in Toldeo and elsewhere in northwest Ohio get their drinking water from Lake Erie, the state government declared the water unsafe to drink (or bathe in and cook with, for that matter).

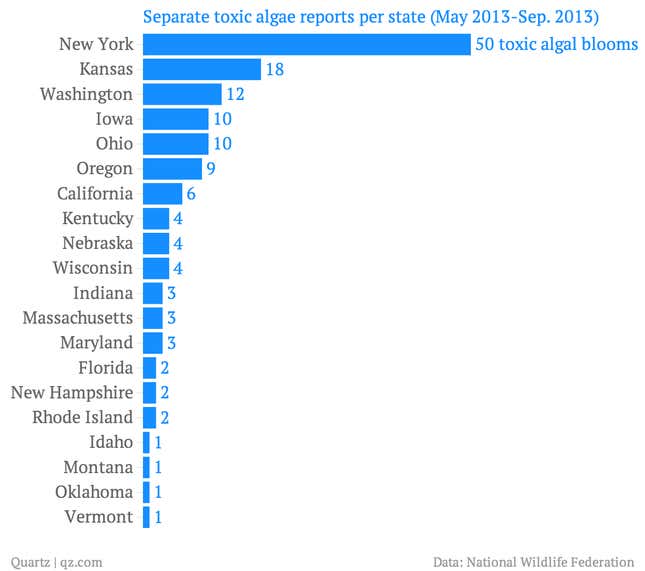

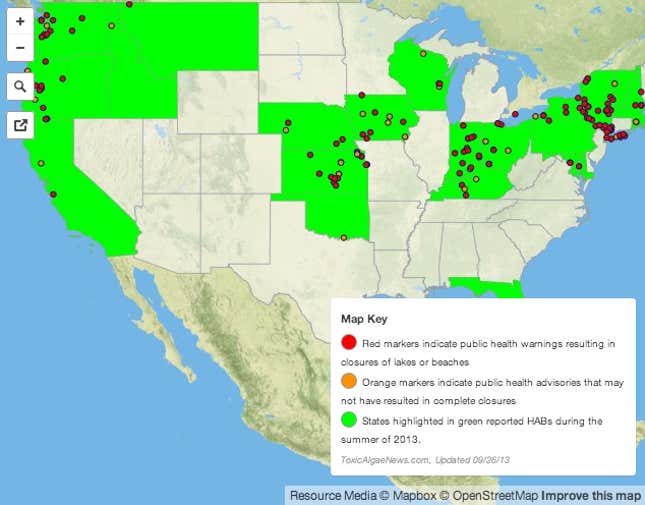

Lake Erie is notorious for its algal blooms. But it’s hardly the only body of water in the US that sees these ecological catastrophes in the summer of 2013 alone:

For instance, Oregon had to commute its Midsummer Triathalon down to a biathalon in Aug. 2013 due to toxic slime clogging Blue Lake. Kentucky reported its first toxic algae problems in the state’s history only in 2013, after visitors to four lakes complained of rashes and stomach pain; the blooms are back again this year. In Florida, toxic algae in Indian River Lagoon killed more than 120 manatees in 2013, say some scientists.

Why is this happening? It’s not that algae are fundamentally bad. In fact, they’re a crucial part of the aquatic food chain. But when you dose algae with phosphorous and nitrogen—which comes from fertilizer and animal feed, as well as human and animal waste—they grow like crazy. At the same time, industrial waste pumped into US waterways has helped kill off the fish that eat the algae. Worse, these blooms strip oxygen from the water, making it harder and harder for the surviving fish to breathe.

In addition to threatening human health, the blooms can destroy whole ecosystems. Take for example Indian River Lagoon, one of the most diverse ecosystems in the US. Not only do local officials drain polluted waters of Lake Okeechobbee into Indian River, but more than 300,000 septic tanks pump human waste into the lagoon—like injecting algae with steroids (here’s a good slideshow of the result). As the bloom blanketed the lagoon’s surface, it blocked sunlight from penetrating the water below, killing nearly 50,000 acres (80 square miles) of sea grass—about the same size as Cleveland—that needs light to photosynthesize. Manatees usually eat around 40 or 50 pounds of sea grass a day. So when the sea grass died off, toxic algae was the only major food option. With so many animals dying, some scientists worry whether it will ever return to full health—grim tidings given that Indian River Lagoon supports a $3.7-billion economy, as well as 15,000 jobs.

The US government recently passed a bill to invest $20.5 million annually in algae bloom research. Getting people, hog farms and soybean farmers to put their waste and agricultural gunk somewhere else, however, will cost a good deal more.