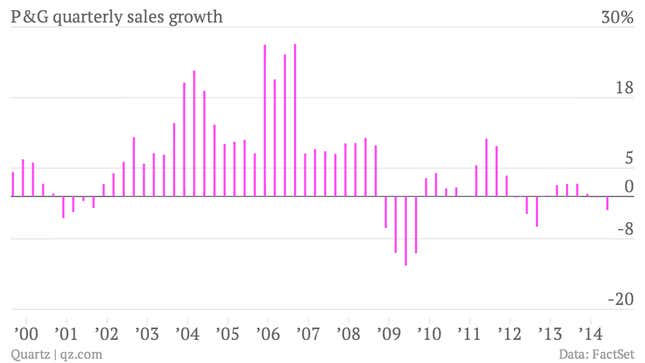

A.G. Lafley’s first stint in charge of Procter & Gamble, from 2000 to 2009, made him something of a legend in business circles. He increased P&G’s value by more than $100 billion, and more than doubled the number of billion-dollar brands in its portfolio. But years of sluggish growth led to the departure of his handpicked successor Robert McDonald, Lafley’s return as CEO, and now, an ambitious plan to cut out as many as 100 fringe brands from the company, according to the Wall Street Journal (paywall).

The company hasn’t exactly been shy about divesting brands in the past. It has entirely exited the food business, where it once owned big brands like Jif peanut butter, Folgers coffee, and Pringles potato chips. It’s in the process of getting out of pet food, even though Iams is a billion-dollar brand.

This latest announcement is an acknowledgement that though Lafley’s strategy during his earlier tenure was effective at getting big, the sheer profusion of brands is now a burden.

In the company’s August 1st earnings call, Lafley said that the 70 to 80 brands that will remain out of about 180 account for 90% of company sales and 95% of its profit.

“In summary, we are going to create a faster growing, more profitable company that is far simpler to manage and operate,” he said on the call. “This will enable P&G people to be more agile and responsive, more flexible and faster. Less will be much more.”

But even as the company gets more efficient, it is creating other problems for itself, Kellogg School of Business marketing professor Tim Calkins points out in a blog post.

According to Calkins, the company will likely lose customers who are attached to brands, unable to switch them over to other P&G products. Fewer brands mean greater opportunities for competitors to grab market share. Also, selling the 90-100 brands that Lafley no longer wants will pose a challenge: these brands have seen their aggregate sales decline 3% and profits drop 16% over the past 3 years—hardly the kind of numbers that send suitors scrambling.

Betting the big core brands will appeal everywhere is risky, too.

“The problem is that focusing on fewer and bigger brands assumes that these will be the preferred choices for shoppers all around the world,” Calkins writes. “I fear that won’t be the case.”

The company’s sluggish growth has come in large part due to a slowdown in the whole consumer products segment. Slimming down might produce better financial results, but it’s not going to change business fundamentals, like the fact that the company’s focus on premium priced products has hurt it with increasingly cost-conscious consumers.