Grade inflation is endemic at American colleges and universities. The most common grade at Harvard, for example, is a straight A, according to its student newspaper.

The distortion has the potential to make high marks mean less, give bad information to degree programs and employers on student performance, and distort how people choose their majors. Those concerns prompted three professors at Wellesley College, a private women’s college near Boston, to study the effects of capping grade inflation for most classes at the school in a paper recently published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

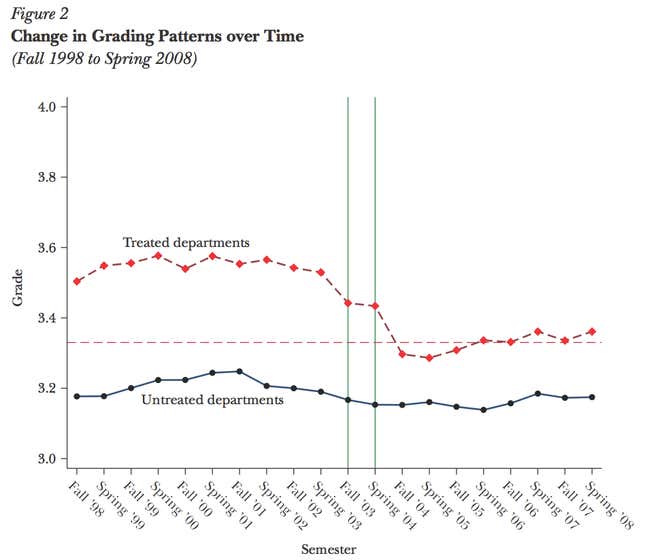

The policy led to a significant reduction in the typical gap in grades between science and math majors and those in the humanities and social sciences.

Students were about 14% less likely to get an A in departments that had to change their grade distribution to fit the new cap. Before the policy, nearly 30% of students in those departments received As. Students were 17% more likely to get Bs, though relatively few received grades below C minuses.

The number of students graduating summa cum laude (the highest honor available) wasn’t significantly affected. Fewer graduated magna cum laude (the next highest honor), which is consistent with having fewer students clustered in the A grade range in a few specific majors.

Student ratings of professors in affected departments went down slightly. The policy exacerbated existing racial gaps in student grades in affected departments. Black and Latino students, who tended to get lower grades before the policy, saw larger negative effects on their grades.

The policy also reduced overall enrollment in affected departments. A lack of inflation is cited as a reason students avoid tougher STEM majors. There was some increased enrollment in the sciences, but the most people switched from social sciences like political science or sociology to economics, possibly because the economics department previously graded on a tougher scale. The humanities stayed flat. Although higher-grading majors reduced their allocation of As, they still gave more As than the sciences.

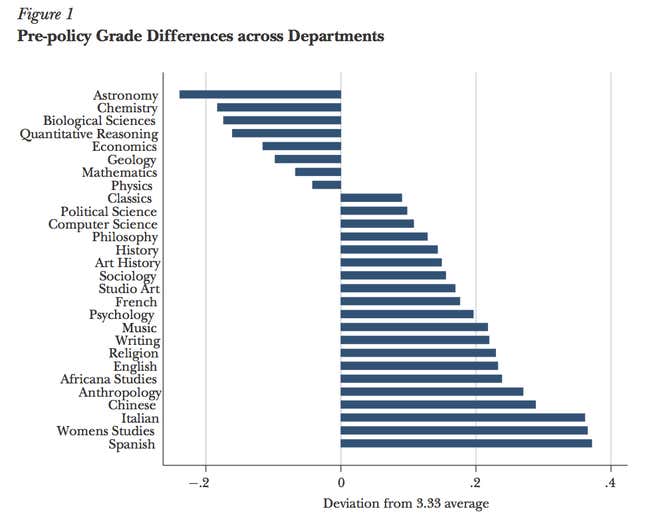

As at most other schools, grades vary wildly across majors. Here are grades relative to the 3.33 average target GPA before the policy went into place:

And here’s the effect on grades over time:

Wellesley’s data isn’t exactly representative of all university students (the college only enrolls 2,300 students). But it does give a sense of what happens when there’s a concerted effort to bring grades back into line.

Fabio Rojas, a Indiana University sociologist who looked at the paper, argues that grade inflation ends up covering up for weakness in academic departments in a blog post:

If you don’t have a strong external job market or external funding, then you can boost enrollments via grade inflation. It also absolves programs by masking racial under performance. The lesson for academic management is this: If you have inequality in funding, departments will compensate by weak grading. If you have inequality by race, departments will compensate by weak grading. Thus, academic leaders who care about either of these issues should implement policies where departments don’t choose standards and are accountable for results.

Ending grade inflation, however, can take a toll on a university’s reputation. Unless all universities enact similar policies, students and alums at the affected universities worry that they can’t compete in the job market.

Image is public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.