For a discipline that purports to measure whether people are better or worse off, economics produces an incredible amount of unhelpful data.

Oft-revised readings of annualized rates of GDP growth. Monthly updates on non-defense capital goods orders, excluding aircraft. Current-account balances. Commercial and industrial loans. Capacity utilization rates.

All of those numbers are hotly anticipated by US traders and a small army of Wall Street economists. And precisely none of them tell you anything substantial about how American households are doing.

Even the monthly jobs report, perhaps the best high-frequency read on the economy, doesn’t usually offer a clear story. A falling unemployment rate can mean more people are getting hired (good) or more people are dropping out of the workforce (bad).

And job growth, while usually treated as an unqualified positive, doesn’t mean that people are actually any better off. (A full-time worker who loses her job and then must take a part-time job at much lower pay is likely to be worse off, not better.)

But lately, something strange has been happening. Wall Street has become obsessed with a simple, easy-to-understand measure of American household health.

“The key focus area is wages…”

—Credit Suisse equity analysts, Aug. 13

“Market participants are scouring a number of wage indicators to assess the outlook for wage growth…”

—RBS economic analysts, Aug. 15

“…the average employed worker’s real wages are going nowhere.”

—Credit Suisse fixed-income analysts, Aug. 14

“Our attention is on other leading indicators of wage growth.”

—Morgan Stanley economic analysts, Aug. 8

It’s no mystery where Wall Street acquired its new-found appreciation for the financial fate of the American working stiff. From her position as the world’s single most powerful economic voice, the chair of the US Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen, is forcing the financial markets to rethink assumptions that have dominated economic thinking for nearly 40 years. Essentially, Yellen is arguing that fast-rising wages, viewed for decades as an inflationary red flag and a reason to hike rates, should instead be welcomed, at least for now.

“It truly is a seminal turning point for how we look at these matters,” Paul McCulley, chief economist at Pimco, one of the world’s largest bond fund managers told Quartz. “And Janet is leading the charge.”

The Great Inflation, an early disruptor

It might sound surprising to most people who work for a living, but for decades the most powerful people in economics have seen strong real wage growth—that is, growth above and beyond the rate of inflation—as a big problem.

To understand why, you have to go back to that golden age of polyester and malaise, the 1970s.

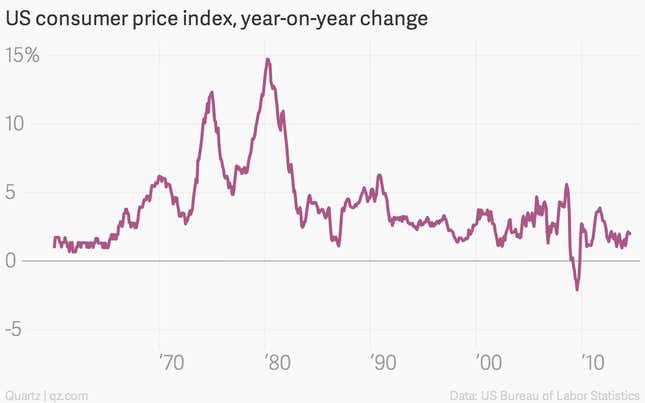

Until the global financial crisis of 2008-09, the price spiral that peaked in 1980 was the most important financial event since World War II. The seemingly inexorable rise was finally crushed when Fed chairman Paul Volcker pushed interest rates to more than 20% and induced a deep recession in the early 1980s.

But the disruption was done. The Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates built around the US dollar had collapsed, as inflation eroded confidence in the greenback. The US banking system was in tatters. The recession Volcker induced in order to tame prices was the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The inflation had also seemingly crushed the credibility of a set of widely held views on economics, the Keynesian consensus. Growing out of the Great Depression and World War II, the Keynesian view held that government management of the economic cycle—through a combination of interest rates and wage and price controls—could keep economies running at full employment without risking runaway inflation. The key was manipulating the traditional relationship of inflation and unemployment—when unemployment is low, inflation tends to be high and vice-versa. In other words, moderately high (but controlled) inflation could help keep unemployment down.

But in the 1970s the US—and much of Europe—found itself with inexplicably high inflation and high unemployment, a.k.a. stagflation. According to the Keynesians, this shouldn’t have been possible. But a new school of economic thought known as monetarism, led by the University of Chicago’s Milton Friedman, had warned that government attempts to keep unemployment low by tolerating slightly high inflation would result in just such a state of affairs.

The stagflation of the 1970s marked the beginning of a decades-long retreat for Keynesian thinking. The monetarist view grew in prestige and influence over the next 30 years, coming to dominate both monetary policy-making and economic thought up until the financial crisis.

The rise of the monetarists

The short version of the monetarist view is that, over the long term, the only thing central banks can do—and therefore should try to do—is keep prices roughly stable.

They believe that rising real wages tend to be a leading indicator of inflation.

That’s because if wages grow, companies pass along the higher costs by raising prices. Workers, seeing the rising prices, bargain for still higher wages. The result is the classic wage-price spiral at the heart of the Great Inflation, or so the story goes.

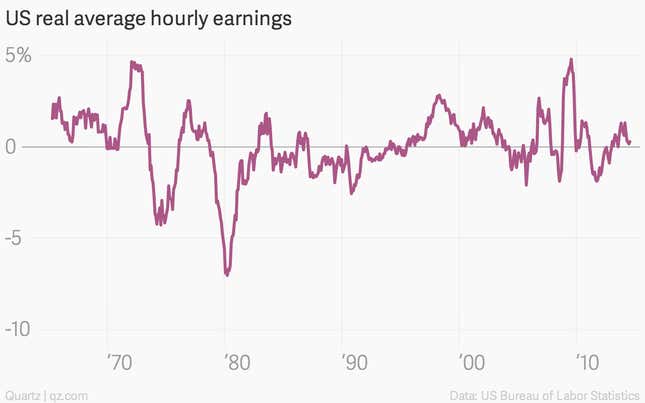

For the monetarists the wage-price spiral, incidentally, helped explain why a sharp rise in real wages around 1970 was followed by a sharp decline in real wages throughout the rest of the decade. Nominal wages were rising, but rising inflation simply devoured their value, as this chart shows:

Since the end of the Great Inflation, the Fed—and most of the world’s important central banks—have gone out of their way to avoid a replay of the wage-price spiral. They’ve done this by tapping on the economic brakes—raising interest rates to make borrowing more expensive and discourage companies from hiring—as wages started to show strong growth.

An understated revolution

It shouldn’t be surprising that Yellen brings a distinct point of view to the subject of wages. She’s a labor economist by background, whose academic mentor, James Tobin, was one of the most prominent American Keynesians.

“She’s looking at wages as more than just an inflation indicator, which is different than most central bankers have done over the last couple decades,” says Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

In fact, Yellen seems to actually welcome outright wage growth. In response to a question about wages at the June press conference of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC, the bank’s rate-setting council), Yellen had this to say:

My own expectation is that, as the labor market begins to tighten, we will see wage growth pick up some, to the point where real wage growth, where compensation or nominal wages are rising more rapidly than inflation, so households are getting a real increase in their take-home pay…

In the wonkish world of monetary policy, such bland-sounding statements carry quite a bit of weight. “Bluntly put: Chair Yellen wants labor to get a fairer share of the fruits of the economy’s productivity,” wrote Pimco’s McCulley in an analysis of Yellen’s comments.

The debate over the true size of the labor market

If Yellen seems ready to make a big bet that the US economy can afford to pay workers more, right-leaning economists—like Harvard’s Martin Feldstein—have regularly warned that wage growth could shoot much higher with little notice.

They argue that the Fed is over-estimating the true size of the labor force, because people who have been out of work for especially long periods won’t be able to re-enter the job market. If the pool of available labor is smaller than expected as more jobs open up, then wages could spike, setting off the wage-price spiral again.

Left-leaning economists dispute this contention. If conditions improve, a lot of even the long-term unemployed will return, they say. That additional supply of labor should exert some downward pressure on wages. So even if wages rise at first, a daisy-chain of price and wage surges won’t follow.

Why things have changed

In her recent speech at the Fed’s meeting at Jackson Hole, Yellen did say that there are reasons to be cautious about higher wages. But she reiterated that the recent “pattern of subdued real wage gains suggests that nominal compensation could rise more quickly without exerting any meaningful upward pressure on inflation.”

And even when wages do start to rise, as Yellen suggests they may, there’s no reason a wage-price spiral similar to that of the 1970s has to ensue.

“These people are stuck in 1977,” David Blanchflower, a prominent liberal economist who formerly served on the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee, says of those harping on the risks of higher inflation. Economists like Blanchflower argue that fundamental shifts in the US economy since then have made it far more difficult for inflation to take hold.

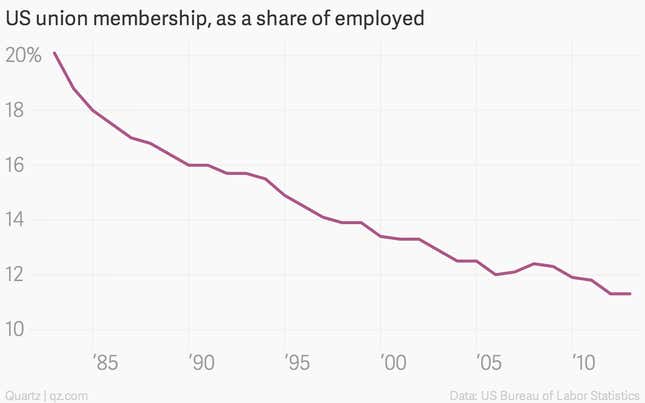

For one thing, union contracts—complete with cost-of-living adjustments that exacerbated the wage-price dynamics—are largely a thing of the past. Come to think of it, so are unions themselves. Just 11% of American workers were unionized at the end of 2013, down from more than 20% in the late 1970s and early 1980s. That greatly reduces the bargaining power of workers, which is important to the wage-price feedback loop.

The economy is also far more insulated from oil-price shocks, which some blame for setting off the Great Inflation in the first place. Greater energy efficiency, falling car ownership, changes in driving habits, and booming domestic energy production will muffle the impact on the US of any sudden rise in world oil prices. Indeed, even as the US economy picks up steam again, petroleum imports are falling. (They hit their lowest level since 2010 in June.) And thanks to the growth of trade, imports are cheaper, which helps keep something of a lid on prices.

In Congressional testimony back in July, Yellen politely pooh-poohed the notion that there’s any near-term need to worry about inflation:

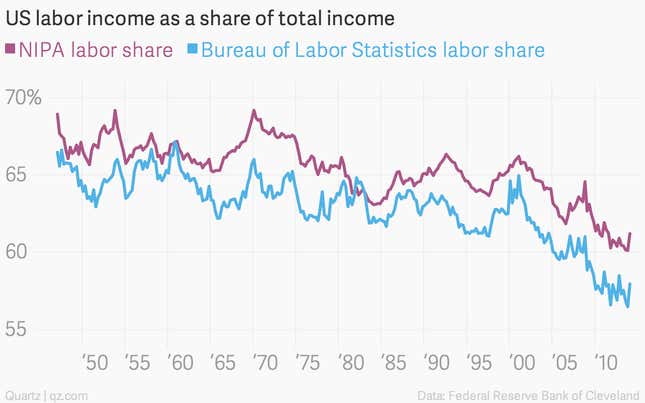

While rising compensation or wage growth is one sign that the labor market is healing, we are not even at the point where wages are rising at a pace that they could give rise to inflation. In fact, real wages have been rising less rapidly than productivity growth and what we’ve seen is a shift in the distribution of national income away from labor and toward capital.

The labor share

That last bit about the distribution of labor and capital is a very delicate topic for all central bankers—but especially for a Fed chair who is a labor economist nominated by a Democratic administration. Right-leaning critics of both the Fed and the Democrats in general are sure to jump on the faintest whiff of redistribution as proof that Yellen is indeed the crypto-technocratic-socialist they’ve been warning about.

But what Yellen is talking about—a shift from labor to capital—is pretty unequivocally clear in this chart.

It shows how labor income has shrunk as a share of national income, thanks to a shift in how the fruits of the US economy have been split (pdf) over the last 30 years. A growing share of the pie is going to investors and businesses rather than workers. Or, in even simpler terms, wages are low, and corporate profits are high.

And this is part of why Yellen is confident that a rise in wages won’t trigger an inflationary spiral. “There is some room there for faster growth in wages and for real wage gains before we need to worry that that’s creating overall inflationary pressure for the economy,” Yellen told Congress in July.

If she’s right, and American paychecks can improve without setting off an inflationary spiral, it could upend the clubby world of monetary policy, reshape financial markets, and have profound implications for everything from American consumer spending and household financial wealth to the country’s worsening income inequality. In other words, higher wages are nothing to fear, and indeed, for most of America, very much something to cheer.