Executive pay in the US has been on an upward trajectory for years now. At an Aspen Ideas festival panel last month, Kroger chairman and longtime CEO David Dillon said something that most corporate chiefs might only utter in private.

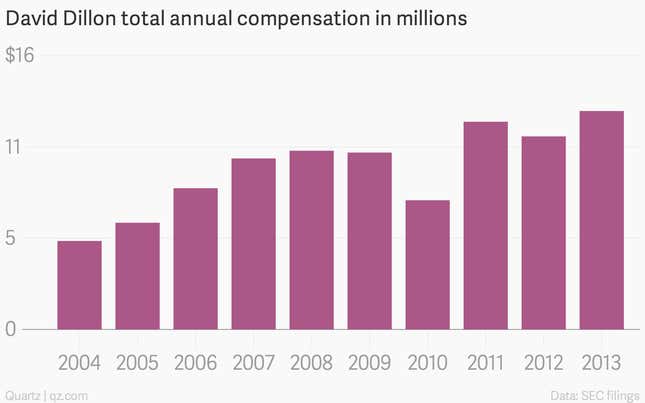

Dillon called his pay package last year ($12,768,695 in total) “ludicrous.”

“While I don’t really defend that amount, it even seems ludicrous to me, it wasn’t that ludicrous at the time they put it together until the stock price went up,” said Dillon, who stepped down from the CEO post of the Cincinnati supermarket chain at the beginning of this year but remains chairman.

And on executive pay in general, Dillon said, “I think it’s also gotten a little extreme or a lot extreme.”

Here’s the full conversation from the panel. Dillon addresses his own compensation at 54.45. A segment on stock-based compensation starts at minute 51.38 in the video and runs to 53.25.

In a recent follow-up conversation with Quartz, Dillon discussed his point further.

“When I used the word ludicrous I was using it in comparison to two things,” Dillon says. “To where I had been paid in previous years, and to what I thought was a more logical level of pay for the year, and it was mostly in reference to the fact that we had a run up in the stock price which made the year look bigger by comparison.”

But he agrees that executive pay has gotten out of hand.

“What I was trying to convey,” Dillon says,”and I’m not sure I did it very well, was that I personally believe that, generally speaking, executive pay has gotten too high, and it needs to be addressed in appropriate ways.”

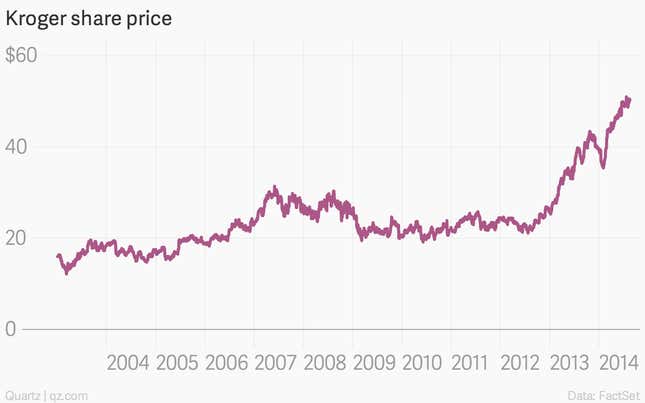

Dillon isn’t kidding about the stock price. Over the past few years, Kroger has been on a tear:

Dillon says he’s been a long-time advocate of moderation, telling his board when he came on as CEO that he wanted restraint. He says he generally targeted and usually hit the bottom 25% of his peer group of executives in terms of compensation.

“I didn’t think I would ever be in a spot where employees here or anywhere would think I’m not highly paid,” Dillon says. “But if you want to try to lead a large employee base—we have 375,000 associates—I wanted them to see that I had shown at least some restraint and had been as concerned about the success in the company and individual associates as I was about my own personal security. I just think you lead from a better position when you do that.”

Here’s a chart of Dillon’s pay through the years. Kroger changed the way it accounted for option grants in 2006, so compensation in 2004 and 2005 is estimated:

Kroger awards executive stock grants based on a fixed-share amounts, and after a several years of a stagnant share price, the board decided not to reduce the number of shares as the stock rose.

“Anybody who looks at CEO pay, even if it was reasonably based, they would say that person is paid way too much,” Dillon says. “We get that impression when the dollar figures are so high. But when I look at what’s expected typically of a CEO, the life expectancy, the lack of job security, the 7-by-24 commitment, I don’t dispute that they ought to be paid really well. It’s just that I think it’s gotten a little bit out of hand.”

As for why, Dillon says at least part of it is paying for talent, that the difference between a good and lousy CEO is huge for both shareholders and employees. Boards often pay up in search of a good one, particularly when they go to an outside candidate. It’s a competition, and boards feel forced or obliged to price up.

That’s not the source of all of the pay inflation, but is at least a contributing factor. As for a solution, Dillon doesn’t think legislation or taxation is the answer, but that more boards should deliberately target more reasonable compensation.