Cyprus has a long history of conflict. But 40 years after it was invaded by Turkey, that conflict is fueling an ongoing dispute over a popular Cypriot cheese.

Last month, the Republic of Cyprus’s ministry of agriculture applied to register halloumi, a semi-firm cheese with a high boiling point, as a protected designation of origin (PDO) in the European Union, which trademarks traditional food products from a region, manufactured in specific way. While the government hopes to prevent overseas copycats, the maneuver has flared tensions on home soil.

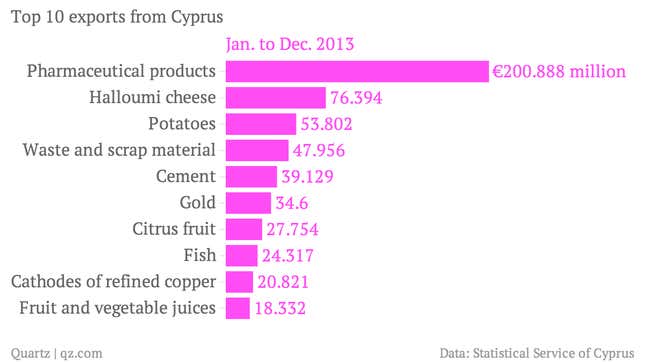

Halloumi is Cyprus’s second biggest export to overseas markets. In 2013, exports were of halloumi were worth €76.4 million ($102 million), up 26% on the prior year, according to the Statistical Service of Cyprus. A decade earlier, halloumi and other Cypriot cheese exports totaled €11.7 million ($17 million). The cheese provides a much-needed fillip for the country’s economy, which was hard hit by the recession.

Unlike other PDOs such as feta or stilton, which belong to specific regions in Greece and England respectively, halloumi is the national cheese of a divided island—which makes the case for geographical certification more complicated.

About one-third of the island became the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (recongized only by Turkey) in 1983. Halloumi, which has been traced back to writings in the mid-16th century when Venetians occupied the island, is made by both Greek Cypriots in the EU-recognized Republic and the Turkish Cypriots, who call it hellim.

While reunification talks are in process, the country remains divided, and inspectors from the government of the Republic of Cyprus are unable to enter the Turkish north to inspect hellim producers—a requirement of the PDO to ensure the recipe is adhered to.

The Cyprus Turkish Chamber of Industry (CTCI), which represents Turkish Cypriot hellim producers, warns that the proposal will prevent them from producing the cheese commercially unless they reunite, inflicting “economic destruction” and “major damage” on the peace negotiations.

Hellim is mainly exported to Turkey and the Middle East—25% of Northern Cyprus’ economy worth about $30 million annually. The CTCI wants to inspect its 40 producers on the ministry’s behalf.

“If we are not included in the PDO registration, we don’t want it to go through,” Doğa Dönmezer, secretary general of the CTCI, told Quartz.

Another sore point of the proposal is the halloumi recipe itself. The PDO stipulates halloumi must contain more than 50% sheep’s or goat’s milk and the rest can be cow’s milk. Many Cypriots from both regions argue cow’s milk should not be used at all in halloumi because it creates an inferior product.

Since 1990, halloumi has been certified as a product of Cyprus in the US that must contain 100% sheep’s and goat’s milk. “The reason we registered it is we wanted to guarantee the consumer that when they ate halloumi it was the real thing,” Dennis Droushiotis, former trade commissioner for the Republic of Cyprus in the US, who was responsible for the certification, told Quartz.

Last year, the US imported $3.3 million worth of cheese and curd from Cyprus, according to the US Census Bureau. And it could come close to doubling that this year, having imported $3.1 million in the first six months of 2014.

“If we didn’t have a trademark, there would probably be a thousand different halloumis out there that would all be junk,” he says.

But some producers are concerned there are not enough sheep and goats in Cyprus to meet the milk quota, which will be enforced 10 years after the PDO is granted. Many shepherds and goat herders were hard-hit by the recession, unable to access credit and forced to sell their livestock. And overseas demand for halloumi is higher in the summer, but the animals produce less milk at this time of year, putting further strain on supply.

Pittas is one the largest and oldest halloumi exporters, having invented the vacuum packaging to sell it overseas. John Pittas, who runs the eponymous dairy company that supplies halloumi to Tesco and Whole Foods, is concerned the milk quota will make exporting “stressful” and result in availability declining. That would lead to prices increasing, opening the gateway to imitators.

“We are a bit worried because as the product is becoming more popular, maybe we will see competition from a similar product—not of the same name and not the same quality—but it will be there if consumers cannot find the real thing,” Pittas says.

“If you can’t drink Champagne, you’ll drink Prosecco.”