My father was physically away more than he was around. Given our globalized economy (in fact, last year business travel was predicted to increase as the global economy improved), there’s no indication that traveling for work will slow in our increasingly connected world.

On the other hand, the negative effects of a growing up with a parent that’s away a lot are well documented. Children with active, present fathers are more likely to be emotionally stable and educationally successful. Meanwhile, having a father who’s absent or not around much has a big impact, especially on boys: it’s linked to aggressive behavior and higher levels of delinquency.

This isn’t a new phenomenon—but technology has made a huge, positive impact on the problem. A 2001 study of workers at the World Bank Group, who have to travel frequently, found that travel contributed to a high amount of stress for both workers and their spouses. This study focused on international travel during 1999, before email, cell phones, and video chatting became prevalent. When questioned about the hardest part of having a frequently traveling parent, “[b]y far the most frequent responses” from children concerned the lack of daily contact.

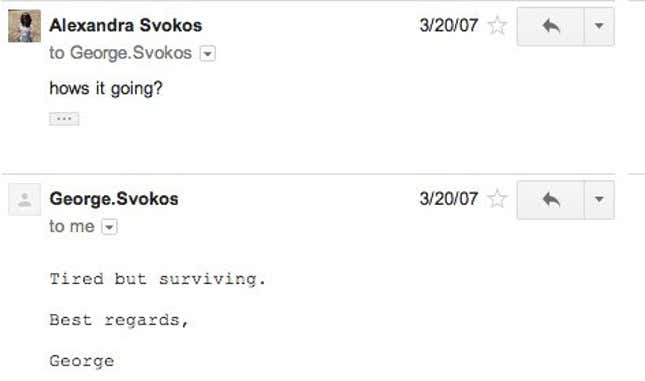

However, at a time when I may have begun to resent my father for being away so much, we became closer. We sent emails constantly—mostly one-liners as I pestered him with questions and he dutifully answered, all signed with his official “Best regards, George.”

Then there were BlackBerrys, with free international BBM and a camera to boot. I’d open my email and find envy-inspiring pictures of wherever in the world my dad was—his perspective, curated.

The book Mobile Technology for Children, edited by Allison Druin, looked into how technology effects parent-child relationships. Druin’s work proved that those cheesy tech commercials are right: used properly, technology bridges distance.

The most important factors of distanced communication are immediacy, regularity, and reciprocity. Fathers don’t have to maintain an exhaustive phone schedule to keep up a relationship with their children; they just have to show up, and do so regularly. Because my dad took the time to send pictures and messages, I knew he still cared about me, no matter how far from home he was at any given time. A pixilated picture with a one-sentence description was often enough.

As Barry Wellman found, digital interactions aren’t replacing face-to-face contact—they’re simply “increasing the overall volume of contact.” An unintended, and welcome, side effect is that these tools of communication also help even the least verbose father express himself, even if it’s through curated images and not words.

The effect that technology has had on long-distance parenting is revolutionary. Druin repeatedly points to real-time interactions as the key to making technology work for you. In fact, if children were unable to share something in the moment—like an image—they were less likely to share the experience at all. Real-time sharing serves as a reassurance as well as an emotional connector. I should know—I’m a proud child of it.