There’s something of a bait and switch going on in the retail end of the seafood business. Thanks to complex fishing supply chains and the light touch of food-safety regulators, the fish you buy from your local store may not be what you think it is. For instance, that red snapper fillet on the ice may not even be from the snapper family. Some of the fish on display may have come from collapsed stocks or were caught by slave labor, among other unconscionable practices.

If that’s not bad enough, now research suggests the fish may contain more contaminants—notably mercury, a neurotoxin that damages brains of fetuses and young children—than you realize.

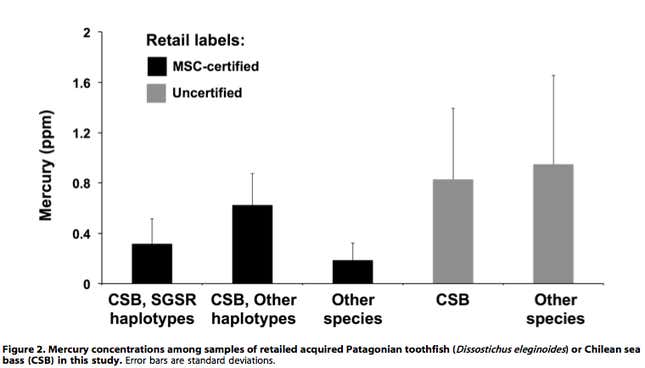

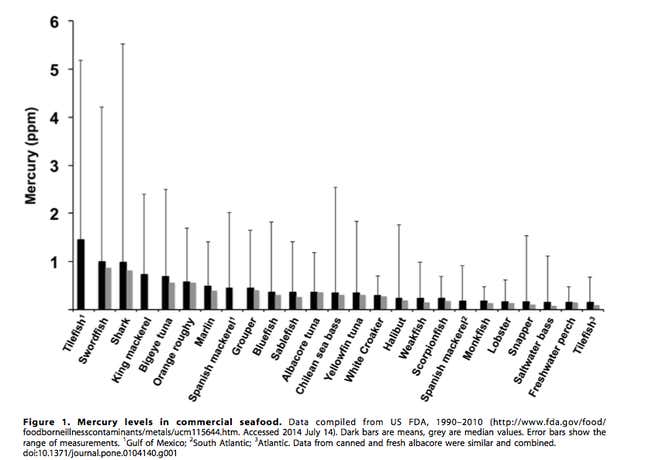

A new study found a “complex pattern of contamination hidden from consumers” among Patagonian toothfish—better known by its marketing-makeover name, “Chilean sea bass”—bought in American grocery stores. Samples sometimes contained higher mercury levels than most countries consider safe, exceeding the 0.5 parts per million limit for imports into Canada and Australia, and sometimes even the 1.0 ppm limit in the EU and US. Typically, this was either because it was actually another species, or the toothfish came from a region with relatively higher mercury contamination.

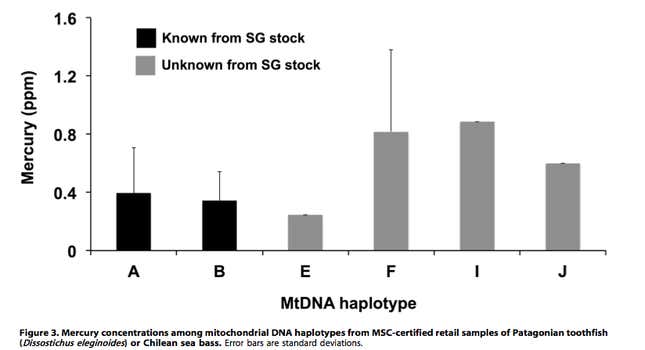

And while consumers who buy fish certified by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC)—the leading independent labeling system for fisheries that meet certain standards for “sustainable fishing or seafood traceability“—might think they’re in the clear, they may well not be. Using DNA testing, the scientists found that nearly a quarter of the Chilean sea bass certified by the MSC to have come from the South Georgia fishery, near Antarctica, was actually from unknown areas, likely closer to Chile, where mercury contamination levels tend to be higher. Three out of 25 samples of MSC-certified Chilean sea bass were another species altogether. (At the time of writing, MSC had not responded to Quartz’s request for comment.)

Chilean sea bass isn’t the only problematic species. Nearly three-fifths of the fish labeled “tuna” in restaurants and grocery stores in the US isn’t actually tuna, as we’ve reported. In New York City, for instance, it’s often tilefish (pdf, p.15), one of the four kinds of fish the US government says should be avoided due to high mercury levels. Studies in Europe have shown similar problems with cod.

As the recent Chilean sea bass and other studies show, though, it’s near impossible for consumers to know what species they’re actually eating—and, therefore, to avoid high-mercury fish. Some examples:

The US’s food regulator advises women who are pregnant or nursing to eat at least eight ounces of seafood per week. It also tells them—along with young children and women who might at some point become pregnant—to avoid fish with high mercury levels. Yet it’s often left to the consumer to determine what fish is safe. As the Environmental Defense Fund’s Tom Fitzgerald explains, the US government runs toxin tests on less than one percent of the billions of pounds of fish imported into the US each year. If labeling can’t be trusted, vulnerable consumers could easily ingest more of the noxious toxin than they’re supposed to.