There are now nearly five times the number of phone models running Google’s Android operating systems in use in the world as there were in 2012.

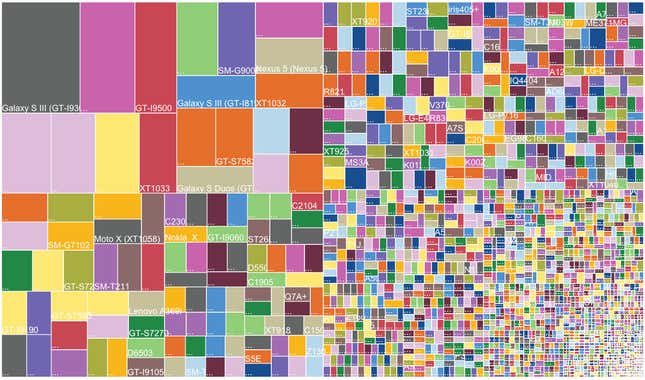

That’s according to OpenSignal, a mobile network analysis company based in London, which found that nearly 19,000 different devices accounted for the last 682,000 downloads of its app. (Google doesn’t disclose these data, but OpenSignal is a reliable proxy, thanks to the worldwide ubiquity of their app.) That is up from nearly 12,000 last year and just under 4,000 in 2012. What that fragmentation looks like can be seen in the image above, which shows the market share of individual models.

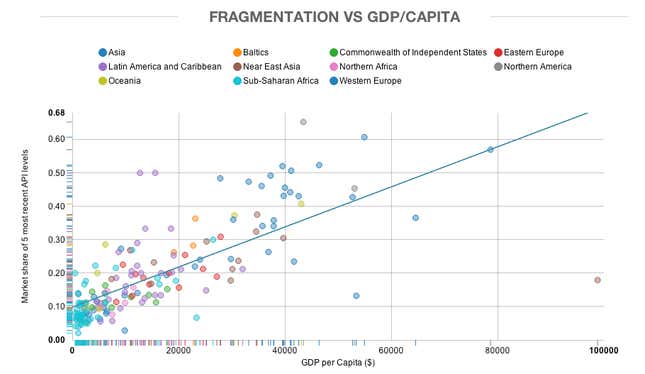

That Android is a heavily fragmented ecosystem is not exactly breaking news. Nor is it particularly shocking that the number of devices is growing exponentially—new brands are popping up all over the place to take advantage of new markets. But OpenSignal, which has been publishing reports on Android’s fragmentation since 2012, has a particularly fascinating way of looking at it this year: The firm crunched the numbers and found that a country’s GDP per capita directly correlates to the level of fragmentation in the market.

OpenSignal looked at the last five versions of the Android operating system—four variations of Kit Kat (4.4) and the final update of Jellybean (4.3.1)—and mapped their combined marketshare to GDP/capita. The results are striking. The tightly packed cluster of light blue dots towards the bottom all belong to Sub-Saharan African countries, where older versions of Android prevail. The top and right half of the chart is dominated by Western European nations, wealthy countries where people frequently update their Android devices. Poor countries are a mess of Android versions, generally running older software on underpowered machines.

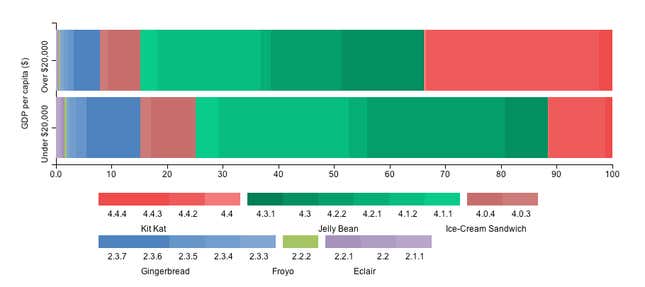

The chart below shows what the operating system distribution looks like if you divide the world into rich and poor. The red and the darkest green are the five latest versions. And again, older versions of Android dominate poorer countries:

It is precisely this problem that Google is trying to solve with AndroidOne, a template that manufacturers of cheap devices can adhere to in order to make decent phones that run modern software. Getting that right is essential for Google if it wants to retain control over the mobile juggernaut it has created, and if it is to ever see a return from its investments in the poor world.